Location: 503 S. Main St., Ligonier, IN 46767 (Noble County, Indiana)

Installed 2014 Indiana Historical Bureau, Ligonier Historical Society, Ligonier Public Library, and Indiana Jewish Federation Friends of Ahavath Sholom

ID#: 57.2014.1

Text

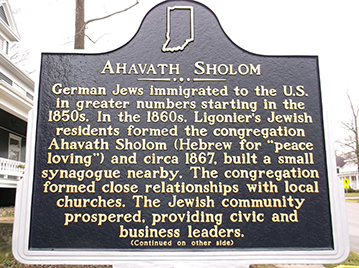

German Jews immigrated to the U. S. in greater numbers starting in the 1850s.1 In the 1860s, Ligonier's Jewish residents formed the congregation Ahavath Sholom (Hebrew for "peace loving")2 and circa 1867, built a small synagogue nearby.3 The congregation formed close relationships with local churches. 4 The Jewish community prospered,5 providing civic and business leaders.6

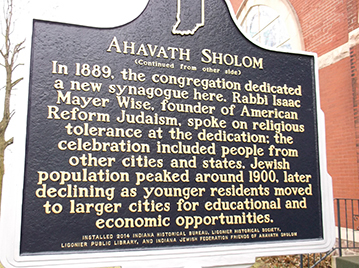

In 1889, the congregation dedicated a new synagogue here.7 Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, 8 founder of American Reform Judaism,9 spoke on religious tolerance at the dedication;10 the celebration included people from other cities and states. 11 Jewish population peaked around 1900,12 later declining as younger residents moved to larger cities for educational and economic opportunities.13

Annotations

Note on Sources: The meeting minutes for the Ahavath Sholom congregation will be cited as "Meeting Minutes," along with the date. The full citation is as follows: "Congregation Ahavas Solem [sic]," Ligonier, Indiana, Minute Book 1888-1917, and Miscellaneous Material, 1929-1949, American Jewish Archives, Collection 35, Microfilm Roll F1333, accessed Indiana Jewish Historical Society Collection, Indiana Historical Society. See footnote 3 for more information on the spelling of the congregation name.

Abstracts of the American Israelite were accessed ProQuest Archiver via IUPUI; microfilm available through IU Bloomington. Ligonier Leader accessed NewspaperArchive.com.

[1] "Frederick Straus," May 22, 1857, List Number 507, Line 6, New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1957, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Noble County Register, March 25, 1858, 2, accessed Indiana State Library (ISL), microfilm; Advertisement, Noble County Register, May 13, 1858, 3, accessed ISL, microfilm; 1860 United States Census (Schedule 1), Perry Township, Noble County, Indiana, Roll M653_285, page 104, Line 17, June 1, 1860, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; "Solomon Mier" and "Mier S & Co.," 1863 Indiana Tax Assessment List, Division 12, Collection District 10, Indiana, U.S. IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1862-1918, accessed Ancestry.com; 1870 United States Census (Schedule 1), Ligonier, Noble County, Indiana, Roll M653_347, page 271B, Line 15, and page 272A, Lines 1 and 12, July 15, 1870, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; 1880 United States Census (Schedule 1), Ligonier, Noble County, Indiana, Record Group 29, National Archives, page 20, Line 14 and 37, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Solomon Mier, Form for a Naturalized Citizen, June 13, 1890, No. 17613, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D. C., accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Jacob Straus, Form for a Naturalized Citizen, May 2, 1894, Number 10328, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C., accessed AncestryLibrary.com; "The Temple Dedicated," Ligonier Banner, September 12, 1889, 4, accessed ISL, microfilm; "In Memoriam," Ligonier Leader, February 24, 1898, 5; Jewish Home Journal 3:9 (April 15, 1898) 73, 75, 78, M743, Folder 11, Box 98, Indiana Jewish Historical Society, submitted by applicant; Jacob Straus, Photograph of Grave, Oak Park Cemetery, Ligonier, Noble County, Indiana, accessed Find-A-Grave; 1900 United States Census (Schedule 1), Ligonier City, Perry Township, Noble County, Indiana, Roll 395, page 10B, Line 33 and page 17B, Line 75, June 12, 1900, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; "Pioneers and Old Settlers," Ligonier Leader, June 20, 1901, 1; 1910 United States Census (Schedule 1), Ligonier City, Perry Township, Noble County, Indiana, Roll T624_372, page 25A, Line 42, June 1, 1860, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Nathan Glazer, American Judaism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957), 23; Lois Fields Schwartz, "The Jews of Ligonier: An American Experience," (Fort Wayne: Indiana Jewish Historical Society, 1978; Hasia R. Diner, The Jews of the United States, 1654 to 2000 (Berkley: University of California Press, 2004), 1-9, 71-88, 99-101; Amy Hill Shevitz, Jewish Communities on the Ohio River: A History (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2007), 34, accessed electronically through the Indiana State Library; "Timeline in American Jewish History," Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, americanjewisharchives.org;

According to historian Amy Shevitz, the population of German Jews increased from about 15,000 in 1840 to about 50,000 by 1850, more than triple the number. Prior to this period, most Jews settled on the east coast, but midwestern towns and cities were drawing German Jews by the 1840s and 50s. There were several reasons for the increasing immigration, explained effectively by Shevitz and historian Hasia Diner. Discrimination and restrictions placed on Jews in central Europe limited options for everything from employment to marriage. At the same time, modernization created fewer positions for peddlers of household goods, a traditional and longstanding occupation for German Jews. According to Diner, economic opportunities determined settlement patterns, so German Jews were searching for a land in need of the peddler. In the mid-nineteenth century, the Midwest was comprised of a widespread network of farming communities, not yet well-connected by canals, roads, or rail. Thus, the Midwest was in need of the peddler's roaming occupation. Usually, the first immigrant to the United States from a German Jewish family was a young single man. He would begin as a peddler, working until he could buy a horse and cart to expand business. In time then he could send for a brother and they could cover more territory and eventually open a dry goods store. This "chain migration" would eventually extend to other family members, causing the Jewish population of small midwestern towns to grow from one or two peddlers to a thriving community.

Jewish settlement of Ligonier parallels the development of German Jewish communities in most other midwestern cities and towns. Secondary sources, such as Schwartz's The Jews of Ligonier, tell a cohesive story of this development. By tracing a few of the known founding members through primary sources (including census records, tax assessment lists, ship passenger lists, death records, and land ownership maps) IHB researchers found support for many of the claims of secondary sources. Frederick William Straus and Solomon Mier were both born in Prussia (in different towns) in Germany in the early 1830s. They came to the United States (likely separately) as young men and worked as peddlers. By the early 1850s, they came to Ligonier, likely drawn by the establishment of a new rail line, and became proprietors of dry goods stores. F. W. Straus was joined by his brothers by the mid 1850s and they expanded their business. Mier also expanded his business and eventually established a bank and a carriage company. The Straus brothers also eventually opened a bank. (See footnote 6 for more information on business endeavors). However, during this period, Ligonier's early Jewish residents were traveling to nearby towns for religious services. The Ligonier Banner described the early history of the men who would form Ahavath Sholom:

Among the first Hebrews that came to this vicinity were the families of Jacob Straus, F. W. Straus, Sol. Mier and Jos Kaufman, and these people formed the nucleus of the present congregation. In 1856, they all attended worship at Auburn, and the next year went to Fort Wayne where they celebrated the leading holy days as is required by their law.

By 1865, the Jewish population had grown large enough to form a congregation. See footnotes 2 and 3 for information on the founding of Ahavath Sholom.

German Jews also thrived in the Midwest because they were generally accepted and supported by their communities. See footnotes 4 and 5 for more information of the acceptance of Jews in Ligonier and other midwestern towns. For information on Jewish immigration to Indiana before the mid-nineteenth century see Timothy Crumrin and Sheryl D. Vanderstel, "Jews in Indiana," Learn and Do: Indiana History, accessed connerprairie.org.

[2] "Meeting Minutes," 1888-1917, passim; Speech of Jacob Straus quoted in "The Temple Dedicated," Ligonier Banner, September 12, 1889, 4, accessed ISL microfilm; "Ligonier and Its New Temple," American Israelite, September 12, 1889, 4; "Notes,"American Israelite, October 24, 1889, 6; "Ligonier, Ind," American Israelite, July 27, 1899, n.p.; "Resolutions," Ligonier Leader, January 21, 1897, 5; "The Dedication: The New M. E. Church Opened on Sunday," Ligonier Leader, January 28, 1897, 4; "M. E. Church Notes," Ligonier Leader, January 28, 1897, 5; "News of the Churches," Ligonier Leader, May 13, 1897, 6; Arthur A. Cohen and Paul Mendes-Flohr, eds., 20th Century Jewish Religious Thought (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2009), 495, 557, accessed GoogleBooks .

In his 1889 speech during the dedication of the new temple (see footnote 6), congregation president and founding member Jacob Straus, stated:

This congregation was originally founded in August, in the year 1865, as a society with ten charter members. In 1866 we changed the same to a congregation, and called it Ahavos Sholom, meaning 'Peace Loving,' at which time we purchased our burial grounds.

There is little consensus about the spelling of the congregation's name. In the 1889 Ligonier Banner article quoted above, the writer chose the spelling "Ahavos Sholom." The Ligonier Leader uses "Ahavath Sholom" during the same period and, indeed, most nineteenth century newspapers use the spelling "Ahavath Sholom." A search of NewspaperArchive.com found seventy-one results for the spelling "Ahavath Sholom," and no results for alternative spellings "Ahavos" or "Ahavas" related to the Indiana congregation. The foremost Jewish newspaper of the period, the American Israelite, also uses the spelling "Ahavath Sholom." The official meeting minutes use several spellings, changing as the secretary recording the meetings changed in the years 1888-1917. The spellings Ahavath, Ahavash, Ahavosh, Ahavas, and even Sholom and Sholem are all found within the minutes. (Copies of these articles and meeting minutes are available in the IHB marker file).

The Hebrew word " ahavah " means love and " shalom " means peace, according to 20th Century Jewish Religious Thought, a collection of thematic essays by renowned scholars. Thus, the varied spellings are likely inconsistencies resulting from translation from Hebrew by the German and English speaking congregation. Several other congregations have shared the name and defined it similarly, including the Texas congregation Ahavath Sholom (est. 1892) and the Massachusetts congregation Ahavath Sholom(est. 1924), both of which define their name as "Love of Peace." According to an email to IHB from Wendy Soltz, Ph.D. candidate in American Jewish History at Ohio State University, the original spelling was likely "ahavat" (in Hebrew: אהבת) and "shalom" (in Hebrew: שלום). Soltz explains, " 'Ahavat Shalom' in Hebrew means 'Peace Loving.' The letter 'tav' in Hebrew produces a 'T' sound. However, in Ashkenazi pronunciation (this congregation was German, so therefore, Ashkenazi) can be said as 'OS', 'AS', [or] 'ATH.' The differences we see in the English spelling are debates in the transliteration of the Ashkenazi pronunciation of the Hebrew 'ahavat,' אהבת."

[3] Speech of Jacob Straus quoted in "The Temple Dedicated," Ligonier Banner, September 12, 1889, 4; Ligonier Leader, January 4, 1900, 5; "Pioneers and Old Settlers," Ligonier Leader, June 20, 1901, 1.

Jacob Straus, the president of the congregation and one of the founding members, recalled the earlier, wooden frame temple during the 1889 dedication of the new temple. The Ligonier Banner quoted Straus: "In 1867 we erected and dedicated the frame building as a house of worship - which we today vacate." The same Ligonier Banner article explained further that the "old temple was dedicated September 1867" and "for over twenty years the congregation worshipped here until growing in members, it was necessary to provide more commodious quarters." A 1901 Ligonier Leader article described Straus's role in the early years of the congregation and reinforced his authority on the history of the 1867 temple: "Mr. Straus has from its organization been one of the most prominent and active members in the society, Ahavath Sholom. He was the first president of the society, which was organized in 1865, and when, two years later, the first temple was built, no one was more actively interested than Mr. Straus."

The original wooden temple remained standing nearby at least until 1900. That year, the Ligonier Leader reported that a man had purchased the "old Jewish Synagogue" and planned to remove the structure to a lot on Grand Street and repurpose it for living.

[4] "Churches," Ligonier Leader, August 20, 1880, 1; Ligonier Banner, May 17, 1888, 5, accessed ISL, microfilm; "Meeting Minutes," July 18, 1896; "Resolutions," Ligonier Leader, January 21, 1897, 5; "The Dedication: The New M. E. Church Opened on Sunday,"Ligonier Leader, January 28, 1897, 4; "M. E. Church Notes," Ligonier Leader, January 28, 1897, 5; "News of the Churches,"Ligonier Leader, May 13, 1897, 6; "The Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Services at Temple Ahavath Solom, Ligonier, Ind.,"Ligonier Leader, February 16, 1899, 1; "Bar Mitzwah Services," Ligonier Leader, March 15, 1900, 4; "Church News,"Ligonier Leader, March 22, 1900; "Ligonier in Mourning," Ligonier Leader, September 26, 1901; "Rabbi Englander Resigns,"Waterloo (Indiana) Press, June 8, 1905, 1, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; Ligonier Leader, November 30, 1905, 8; "The Temple," Ligonier Leader, March 20, 1913, 5; Ligonier Leader, May 25, 1916, 3.

Over several decades, the pastors of the Ligonier Methodist Episcopal Church and the rabbis of Ahavath Sholom spoke at each other's services. The congregations celebrated the building of new places of worship together in the nineteenth century and mourned a fallen president in the twentieth. The Ligonier newspaper collection at the Indiana State Library is scattered, but at least by 1880, the Ligonier Leader (established that year) was running weekly notices for the Friday and Saturday services of Ahavath Sholom alongside similar notices for Christian church services. In 1888, the Ligonier Banner reported that while the congregation Ahavath Sholom celebrated the Feast of the Pentecost in their temple, they were joined by "a large number of our gentile citizens" who enjoyed the Rabbi's lecture.

The "Meeting Minutes" show that in 1896, the congregation resolved to offer their temple to the M.E. Church while they built their own church. In 1897, the Ligonier Methodist Episcopal Church passed a resolution to "express their most sincere thanks to the congregation of Ahavath Shalom for their great kindness, shown in the tender of the beautiful temple of worship for our use during the erection of our own church. That we will always cherish for them a kindly feeling, even brotherly love, for this, their kindness to us." The Ligonier Methodist Episcopal Church was dedicated and opened to the public Sunday, January 24, 1897. One of the speakers at the ceremony was Rabbi Magil of Ahavath Sholom.

That same year, the Ahavath Sholom Congregation passed a resolution thanking the pastors of several local churches as well as the superintendant of public schools "for having occupied our pulpit at intervals during the past few months, delivering a course of interesting and instructive lectures, and we, in behalf of the congregation, beg to assure them that these lectures were highly appreciated and proved of great value, bringing about a closer union, which we trust will always continue." In 1899, Ligonier citizens gathered at the temple to hear the Rabbi of Ahavath Sholom, ministers of local Christian churches, G. A. R. representatives, and the Colonel of the 157th Indiana speak on "the heroic deeds of American soldiers and sailors during the American-Spanish war of recent months."

In 1900, Jewish and gentile Ligonier citizens attended Bar Mitzvah services at the temple. The Ligonier Leader printed weekly announcements for services at Ahavath Sholom around this time as well. In 1901, Ligonier citizens attended mourning services upon the death of President McKinley at the Methodist Church. Rabbi Englander of Ahavath Sholom was among the speakers. According to the Waterloo Press in 1905, "When the Jewish synagogue was given a new dress, services were held in the Methodist Church, and the Methodists have had no more hesitancy in holding their services in the Jewish synagogue when occasion suggested it, than they would have felt in going to the Baptists or Presbyterians." That same year, the Ligonier Leader reported that the Rabbi of Ahavath Sholom conducted Thanksgiving services at the Methodist Church. A 1913 announcement for services at Ahavath Sholom stated: "Everybody welcome." While further research is needed to determine the extent of the exchange of pulpits between the Ahavath Sholom Rabbi and the Methodist pastor, a Ligonier Leader article shows that the Rabbi delivered a sermon at the Methodist Church in 1916.

[5] Noble County Register , March 25, 1858, 2, accessed ISL, microfilm; Advertisement, Noble County Register, May 13, 1858, 3, accessed ISL, microfilm; "Solomon Mier" and "Mier S & Co.," 1863 Indiana Tax Assessment List, Division 12, Collection District 10, Indiana, U. S. IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1862-1818, accessed Ancestry.com; M. Jacobs & Co, "Articles of Agreement," February 19, 1878, M743, Folder 3, Box 1, Indiana Jewish Historical Society, Indiana Historical Society, Copy submitted by applicant in IHB marker file; Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society, Grand Social Ball Invitation, October 10, 1884, M743, Folders 11, Box 95, Indiana Jewish Historical Society, Indiana Historical Society, submitted by applicant; "Religious: Matters of Interest Gathered from the Bureau of Statistics Concerning the Churches of Indiana," Martinsville Weekly Gazette, December 13, 1884, 3, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society, Grand Charity Ball Invitation, October 21, 1886, M743, Folders 11, Box 95, Indiana Jewish Historical Society, Indiana Historical Society, submitted by applicant."The Temple Dedicated," Ligonier Banner, September 12, 1889; "Bequests for Charity," Goshen (Indiana) Democrat, April 25, 1900, 3, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "Rabbi Magill Resigns," Indianapolis Sun, August 23, 1900, 2, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "Rabbi Englander Resigns," Waterloo Press, June 8, 1905, 1, NewspaperArchive.com; Leon Wertheimer to Joseph Levine, June 7, 1963, 5, 11-12, M743, Folders 3, Box 95, Indiana Jewish Historical Society, Indiana Historical Society, submitted by applicant; Jo Kann Rothberg, "Growing Up As A Jew in Ligonier, Indiana," March 15, 1981, 3-4, M743, Folders 14, Box 98, Indiana Jewish Historical Society, Indiana Historical Society, submitted by applicant; Judith E. Endelman, The Jewish Community of Indianapolis: 1849 to the Present (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), 2-3. See footnote 1 for census record and tax assessment citations that show occupations of several prominent citizens (physical copies in IHB marker file).

The Jewish population of Ligonier continued to grow throughout the nineteenth century. Prominent members of Ahavath Sholom expanded their businesses from dry goods to real estate and banking. Jewish residents established branches of organizations such as the Independent Order of B'nai B'rith (I.O.B.B.) which provided charity and assistance to families of members who made contributions for this purpose. The I.O.B.B. and the Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society hosted social events. In 1884, the State Board of Statistics reported that the congregation Ahavath Sholom had grown to include 45 members. Most notably, by 1888 the meeting minutes show that the congregation had outgrown their synagogue and made plans for a newer, larger edifice. See footnote 7 for more information on the new temple. In 1900, the Indianapolis Sun described Ligonier as "one of the foremost Hebrew communities in the United States." The Goshen Democrat reported on the generous financial contributions made by prominent Ligonier resident and Ahavath Sholom member Jacob Straus to several Midwest institutions including Hebrew Union College. By 1905, the Waterloo Press estimated that the population of Ligonier was 35 percent Jewish with "a comingling that is probably not found in any other city in the country."

An important reason for the growth and prosperity of Ligonier's Jewish community was its acceptance by the non-Jewish residents of Ligonier. This was not unusual. According to historian Judith E. Endelman, because the first Jewish residents of Indiana towns and cities were merchants who prospered and aided the economic growth of their communities, they became well-respected citizens. Endelman states, "Because of the public nature of the retail trade, these early German Jewish merchants became well-known in their communities." An early example of community support in Ligonier appeared in an 1858 article in the Noble County Register; the paper reported that prominent Jewish citizen Solomon Mier and others were "erecting a large business block" in Ligonier, noted that it was an "improvement" that they "hope will stimulate others in the place to do likewise," and wished "success to you gentlemen." Starting in the 1850s, local newspapers ran ads for Jewish businesses and printed positive and supportive notices when the stores made improvements or offered new goods.

Upon the dedication of the new temple in 1889 (see footnote 7), the Ligonier Banner wrote:

The Hebrews of Ligonier now worship God in their new Temple, and Ligonier can pride herself upon the new place of worship, as in all probability, there is no other town of as small population, in the United States that has a building of the kind that will compare with that of the Ahavos Sholom Congregation. It is indeed a credit to our town and country.

Reminiscences of elderly Jewish Ligonier residents collected by the Indiana Jewish Historical Society from the 1960s-1980s show that Jews felt accepted in the city. Leon Wertheimer recalled that Ligonier was "very liberal in respect to the opportunity of all Jewish people to mingle socially with all other religious groups . . . there was no feeling of prejudice." Jo Kan Rothberg recalled, "I see now that to be a Jew in Ligonier was to wear a badge of honor. . . This is the way I remember Ligonier - accepted in all ways, yet knowing I was different." She continued, stating that there was a "certain ingredient which made Ligonier so special: a productive partnership which can evolve when disparate cultures and religions become bridges rather than barriers."

[6] Noble County Register , March 25, 1858, 2, accessed ISL, microfilm; 1863 Indiana Tax Assessment List, U. S. IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1862-1918, accessed Ancestry Library Edition; 1864 Indiana Tax Assessment List, U. S. IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1862-1918, accessed Ancestry Library Edition;1865 Indiana Tax Assessment List, U. S. IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1862-1918, accessed Ancestry Library Edition;1870 United Stated Census; "Business Directory for the Cities and Villages of Noble County" inAn Illustrated Historical Atlas of Noble County, Indiana (Chicago: Adreas & Baskin, 1874), accessed GoogleBooks; 1880 United States Census; Ligonier City Council, "In Memoriam," February 24, 1898, transcribed in Schwartz, 9-10; "Resolutions of Respect," Ligonier Leader, March 3, 1898; Jewish Home Journal 3:9 (April 15, 1898) 73-80, M743, Folders 11, Box 98, Indiana Jewish Historical Society, Indiana Historical Society; "Pioneers and Old Settlers," Ligonier Leader, June 20, 1901, 1; "Library News," Ligonier Leader, September 3, 1908, 6;"Leo Srole, "Report of Findings in a Preliminary Community Survey of the Jewish-German Group of Ligonier, Indiana (August, 1938) 51-52, in Schwartz, 13-14; Schwartz, 5-15.

In her 1978 publication "The Jews of Ligonier," Lois Schwartz traces the business successes of some of Ligonier's most prominent Jewish citizens, the families of F. W. Straus and Solomon Mier. Primary sources such as newspaper articles, business advertisements, and tax and census records confirm the claims made by Schwartz for these residents. (Footnote 1 gives information on the arrival of Straus and Mier in Ligonier in the context of increasing Jewish migration in the United States in general.) Straus found success running a general store in Ligonier starting in the 1850s. He was soon able to bring his brothers, Mathias and Jacob, to the U.S. from Germany as well. The Straus brothers founded a farm brokerage firm and a bank in the 1860s. Like F. W. Straus, Solomon Mier ran a general store in Ligonier in the 1850s and opened a bank in the 1860s, bringing family into his business operations. Solomon Mier and Company expanded into the carriage manufacturing business and land brokerage. Tax assessment lists show the multiple properties and companies of both Mier and Straus in the 1860s. An 1874 business directory confirms that by that year, both men had established banks, with the Straus brothers also involved in real estate and insurance. Census records from 1870 and 1880 confirm these occupations. Schwartz notes that many Jewish residents found success in Ligonier in clothing and general merchandise, grain and livestock, and land brokerage dealings, but others who worked for such companies lived modestly. A survey by Leo Srole claimed that Jewish-owned stores earned a third of total sales for all stores in Ligonier in 1878 and that the businesses of Mier and Straus "accounted for the major part of all Jewish sales." Advertisements running in the Ligonier Banner during the 1880s show that Straus & Co. were involved in banking, fire and life insurance, selling "passage tickets" to Europe, and purchasing grain, seeds, and wool. In 1898, the Jewish Home Journal credited F.W. Straus with major economic improvements for Ligonier: "[Straus] has made Ligonier one of the best wheat markets in the state...and it is natural to conclude that all other improvements of the town are in a large per centum the result of the great prominence we had acquired as a market for everything the farmers could produce and offer for sale."

The Straus and Mier families used their financial success to improve their community, notably through the creation of the synagogue, but also through other endeavors. As early as 1858, the Nobel County Register noted that Mier was making improvements to downtown Ligonier by "erecting a large business block." According to secondary sources, Straus was essential to improving the financial situation of the town and in organizing a school board and building a public school in Ligonier in 1876. The Marshall County Republican confirmed in 1877, "the new school-house in Ligonier has just been completed."

After F. W. Straus's death in 1898 the City Council of Ligonier passed a "Resolution of Respect" which was printed in the Ligonier Leader. The council noted Straus's "valuable service by the inauguration of reform and the introduction of wholesome business methods" during his service as a member of the Board of Trustees. The resolution continued recalling Straus's "well-directed efforts to bring order out of chaos, to lay the foundation for a properly conducted town government, providing the means for the extinguishment of a long standing debt, and making possible certain much needed public improvement, (including the erection of a splendid educational institution,) and habilitating the town with financial stability and credit not hither to enjoyed." The Jewish Home Journal also noted Straus's role in organizing Ligonier's finances upon his passing.

Schwartz describes Solomon Mier as "the prime mover" in installing a sewer system in Ligonier, and notes that as a city council member he insisted the water department remain publicly controlled. Schwartz lists several other Jewish citizens that served as town trustees, city council members, and even as mayor of Ligonier, citing "Ligonier Official Town and City Records," 1890-1956. More research is needed to determine the extent of Ligonier's Jewish residents' involvement in political and civic roles. Also noteworthy, in combination with Carnegie funds, prominent Jewish families were responsible for building and furnishing a public library which opened in 1908.

[7] "Meeting Minutes," July 1, 28, August 12, September 2, October 7, February 3, March 19, May 16, July 17, August 4, 1889; Ligonier Banner, May 17, 1888, 5, accessed ISL, microfilm; "The Temple Dedicated," Ligonier Banner, September 12, 1889, 4, accessed ISL, microfilm.

The only surviving book of "Meeting Minutes" of the Board of Trustees for the congregation Ahavath Sholom begins in July 1888; the first several entries show that the board was already planning the building of a new temple. The minutes for July 28, 1888 record the motion made and carried "that the Trustees should make arrangements [and] proceed with building the new Temple after having adopted a plan [and] consulted with the congregation." Over the next year, the minutes also document the choosing of architect and plans, fundraising, and plotting a cemetery. The Ligonier Banner reported that "early in 1888" the congregation appointed a building committee to work "toward the erection of a new temple" for the growing congregation. By 1888, the growing congregation also employed a full-time rabbi "with the understanding that a new temple was to be built at once."

The new temple was dedicated September 6, 1889. The Ligonier Banner described in detail the building and the event in an article published the following week. Rabbi Epstein, the congregation's regular rabbi, "called together" the congregation at the old building for a "formal leave taking of the old temple." Scrolls were moved from the old temple to the new as the Ligonier Military Band played. Congregation president Jacob Straus gave a history of the Ahavath Shalom congregation. (Footnotes 2 and 3 detail this history). Straus thanked and credited the "congregation, although only twenty-two in number, as also our friends at home and abroad and in particular, encouraged and liberally assisted by the Ladies' Ahavos Sholom Society, Ladies' Benevolent Society, as also by the Young People's Charitable Union." Cincinnati Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise gave the dedication address. See footnote 8-10 for more information on Wise and footnote 10 for more information on his dedication speech.

[8] "People & Ideas: Isaac Mayer Wise," God in America, accessed www.pbs.org; Peter Egill Brownfeld, "Isaac Mayer Wise: The Father of American Judaism,"Issues of the American Council for Judaism (Fall 2005), accessed www.acjna.org; "Isaac Mayer Wise," Isaac Mayer Wise Digital Archive, The Jacob Rader Marcus Center, American Jewish Archives, accessed americanjewisharchives.org; Union for Reform Judaism, "History of the Reform Movement," accessed www.urj.org; Jewish Newspapers and Periodicals," American Memory, Library of Congress, accessed http://memory.loc.gov.

Isaac Mayer Wise (1819-1900) was a leading rabbi considered the "father" or the "architect" of American Reform Judaism in the nineteenth century. According to Brownfeld's essay, "from his arrival in America in 1846 to his death in 1900, the rabbi was devoted to modernizing and Americanizing Judaism." He rejected many rituals and restrictions he saw as outmoded and unrelated to the spiritual aspects of Judaism. He encouraged desegregation of the sexes during services, advocated use of German and English instead of Hebrew, and paid little attention to traditional dietary restrictions. According to a short PBS article, "He envisioned Judaism as a progressive religion that needed to be creatively adapted to modern culture, not a fixed tradition to be maintained." According to the American Jewish Archives, Wise founded several major institutions that continue his work today including, The Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, and the Central Conference of American Rabbis. He wrote extensively throughout his life, publishing books of theology and history, as well as editing two newspapers, including the Israelite, cited by the Library of Congress as "the major nineteenth century American Jewish newspaper." His editorials and other contributions to periodicals can be accessed through the American Jewish Archives.

In 1873, Rabbi Isaac Wise led the founding of the Union of Hebrew Congregations with the purpose of uniting congregations around the country and founding the Hebrew Union College (established in 1875) to train American rabbis. The Union of Hebrew Congregations is known today as the Union for Reform Judaism, which refers to Wise "the founder of Reform Judaism in North America." Historian Hasia Diner refers to the period between the 1850s and 1880s as "the age of Wise" and the "triumph" of his moderate Reform Judaism in the United States. (Diner notes that Rabbi David Einhorn brought reform ideas to the United States from Europe earlier, in the 1840s, but his much more radical teachings did not have the influence that Wise's had over American congregations.) For more information on his role as "father of American Reform Judaism," see footnote 9.

A short biography of Wise is available through PBS's God in America program. A more extensive, article-length biography is available through The American Council for Judaism. A comprehensive collection of his published writing and private correspondence is available through the Isaac Mayer Wise Digital Archive. For a full-length biographical analysis of his life and career see: Sefton D. Temkin, Isaac Mayer Wise: Shaping American Judaism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

[9] Ibid.; American Israelite , October 24, 1889, 6, abstract accessed ProQuest Archiver; Diner, 120-122; Timothy Crumrin and Sheryl D. Vanderstel, "Jews in Indiana,"Learn and Do: Indiana History, accessed connerprairie.org; Lawrence A. Englander, "History of Reform Judaism and a Look Ahead," Reform Judaism Magazine (Summer 2011).

The Reform movement originated in Germany in the early 1800s and began making its way to the United States with rabbis who came in the 1840s. In general, Reform Judaism sought to adhere to Judaism's ethical principals, but adapt the religion to modern life. While specifics varied among congregations, changes included the addition of music to services for inspirational purposes, desegregation of the sexes in seating and choirs, and a softening of restrictions on diet and Sabbath activities. According to an article by historian Lawrence Englander the nineteenth century Reform movement was "a period of adaptation to the wider gentile community" during which restrictions on diet, dress, and other ritual practices were abandoned. Theology was reformed as well. According to Englander, instead of praying for the coming of the Messiah, they focused on "the Jew's historic task to bring social justice to the world from within the lands where they lived." Thus Reform Judaism changed the Jewish experience "from an all-encompassing way of life to simply a religion … in all other respects Jews were just as European or American as their non-Jewish neighbors next door." Most scholars refer to Rabbi Isaac Wise as the "founder" or "father" of American Reform Judaism. See footnote 8 for more on his role in creating a Reform movement.

It is not clear when Ahavath Sholom became a reform congregation, or if they always functioned as such. According to an article by Crumrin and Vanderstel, by 1880, "the majority of synagogues around the state followed Rabbi Wise's 'Reform fellowship.'" The position of honor given Wise at the 1889 dedication confirms that Ahavath Sholom was firmly established as a Reform congregation by that time. That same year the American Israelite reported that the Congregation Ahavath Sholom had become a member of the Union of Hebrew Congregations, the major Reform organization in the United States, founded by Rabbi Wise. See footnote 8 for more on the Union of Hebrew Congregations.

[10] "Meeting Minutes," July 17, 1889; Isaac M. Wise, photocopy of inscription in book, September 6, 1889, M743, Folders 5, Box 96, Indiana Jewish Historical Society, Indiana Historical Society, submitted by applicant; Ligonier Banner, September 12, 1889, 4.

Isaac M. Wise gave the dedication address at the Friday, September 6, 1889 celebration. According to the Ligonier Banner, "his advanced views upon the subject of worship showed him to be a liberal of liberals." Wise praised the freedom of religion offered by the United States. The Banner quoted Wise at length:

I am proud that I am an American citizen, and that our broad land is dotted from ocean to ocean with places of worship protected by the strong arm of religious tolerance and soulful devotion. To worship God in accordance with the dictates of his own conscience is a right that every loyal, patriotic and country loving citizen should guard, not only with his life blood, but with all the force of his intellectual being.

The following day, Saturday, September 7, 1889, Wise delivered the sermon at the Sabbath services to a large audience. The Banner reported that his Sunday lecture on "Footprints of Judaism in the World's History" was "doubly interesting to those not identified with his church."

See footnote 7 for more information on the dedication and footnote 8 for biographical information on Wise.

[11] Ligonier Banner , September 12, 1889, 4.

The Banner reported that people from all across Indiana attended the dedication, as well as visitors from large cities like Chicago, New York, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and smaller midwestern cities like Hopkinsville, Kentucky, and Clinton, Iowa. The Banner also reported that a "large number" of Ligonier citizens also attended. Since the congregation numbered only twenty-two members at the time of the dedication, it is likely this "large number" included non-Jewish Ligonier residents. The Sunday banquet "given by the ladies of the congregation in honor of the dedication" was attended by over two hundred people and thus also likely included non-Jewish residents. Out of town guests, including Rabbi Wise, also attended this event. After the banquet, "the guests, with but few exceptions, repaired to City Hall, where the festivities were continued in a grand ball."

[12] "Rabbi Magill Resigns," Indianapolis Sun, August 23, 1900, 2, NewspaperArchive.com; Joseph Levine to Dr. Schappes, May 29, 1974, M743, Box 95, Folder 3, Indiana Jewish Historical Society, Indiana Historical Society, submitted by applicant; Leon Wertheimer to Joseph Levine, June 7, 1963, 5, 11-12, M743, Folders 3, Box 95, Indiana Jewish Historical Society, Indiana Historical Society, submitted by applicant; Lois Fields Schwartz, "The Jews of Ligonier - An American Experience," (Fort Wayne: Indiana Jewish Historical Society, 1978), 5, 21; Lee Shai Weissbach, "Decline in an Age of Expansion: Disappearing Jewish Communities in the Era of Mass Migration," American Jewish Archives Journal 49 (1997): 39-61, accessed American JewishArchives.org; "Vital Statistics: Jewish Population in the United States by State," Jewish Virtual Library, accessed jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

In 1900, the Indianapolis Sun referred to Ahavath Sholom as "one of the foremost Hebrew communities in the United States." According to Levine, "There were about 200 Jewish men women and children in Ligonier at about 1900." According to Wertheimer, "In 1900 there were 43 Jewish homes in Ligonier all with families, and the Jewish population at the time was between 250 and 300 people." According to Schwartz, by 1900 Ligonier was "a thriving city and business center of about 2,000 people, including fifty-five Jewish families (more than 200 Jews)." She refers to 1900 as the "zenith" and "apex" of the Jewish community and population in Ligonier.

[13] Ligonier Leader , May 11, 1899, 4; Ligonier Leader, July 20, 1899, 4; "Bar Mitzwah Services," Ligonier Leader, March 15, 1900, 4; "Dr. Magil Says Farewell," Ligonier Leader, November 8, 1900, 4; "A Rabbi Chosen," Ligonier Leader, May 30, 1901, 5; "Rabbi Englander Resigns,"Waterloo Press, June 8, 1905, 1, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "Soon to Leave Us," Ligonier Leader, June 29, 1905, 5; Ligonier Leader, November 30, 1905, 8; Ligonier Daily Leader, March 8, 1906, 2; Ligonier Leader, September 5, 1907, 3; "Confirmation Services at the Jewish Temple," Fort Wayne Journal Gazette," June 7, 1908, 2, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, September 5, 1909, 11, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; Ligonier Leader, October 6, 1910, 5; "Death of Jacob Baum," Ligonier Leader, August 10, 1911; "The Temple," Ligonier Leader, March 20, 1913, 5; Ligonier Leader, December 2, 1915, 5; Ligonier Leader, May 25, 1916, 3; Stanley J. Straus, Affidavit No. 11816, March 23, 1922, Noble County, Indiana, recorded March 31, 1923, submitted by applicant, copy in IHB file; Solomon Mier, Photograph of Grave, Oak Park Cemetery, Ligonier, Noble County, Indiana, accessed Find-A-Grave; Jacob Straus,Photograph of Grave, Oak Park Cemetery, Ligonier, Noble County, Indiana, accessed Find-A-Grave; Pamphlet, "Congregation Ahavath Sholom, Ligonier Indiana, Confirmation Services," June 7, 1925, Folder 7, Box 95, Indiana Jewish Historical Society Collection, 1845-2002, No. M743, Indiana Historical Society; "Meeting Minutes," April 10, 1942, January 22, 1943, September 10, 1946; E.L. Mier to Congregation Ahavath Sholom, September 8, 1947, "Miscellaneous Material, 1929-1949," American Jewish Archives, Collection 35, Microfilm Roll F1333, accessed Jewish Historical Collection, Indiana Historical Society; "List of Members of the Congregation Ahavas Sholem," March 27, 1948, "Miscellaneous Material;" Robert L. Katz to Henry Kaplan, May 11, 1949, "Miscellaneous Material;" Leon Wertheimer to Joseph Levine, June 7, 1963, 5, 11-12, M743, Folders 3, Box 95, Indiana Jewish Historical Society, Indiana Historical Society, submitted by applicant; Joseph Levine, "Dedication Speech," July 13, 1975, M743, Folders 8, Box 96, Indiana Jewish Historical Society, Indiana Historical Society, submitted by applicant; Lois Fields Schwartz, "The Jews of Ligonier -- An American Experience," (Fort Wayne: Indiana Jewish Historical Society, 1978), copy available Indiana Historical Bureau marker file; Alex Vagelatos, "Former Temple Now Museum," Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, September 9, 1989, Living Section, Folder 7, Box 95, Indiana Jewish Historical Society Collection, 1845-2002, No. M743, Indiana Historical Society; Lee Shai Weissbach, "Decline in an Age of Expansion: Disappearing Jewish Communities in the Era of Mass Migration," American Jewish Archives Journal 49 (1997): 39-61, accessed American JewishArchives.org; Crumrin and Vanderstel, "Jews in Indiana," n.p.; "The Demise of Community," in Shevitz, Jewish Communities on the Ohio River, 173-189.

According to an article by historian Lee Shai Weissbach, between 1880 and the mid-1920s, the Jewish population of the United States increased greatly, mainly because of the immigration of Eastern European Jews. Despite this "age of expansion," some small communities which were established in the mid-nineteenth century, like Ligonier, went into decline after the turn of the century. Weissbach explains that because most small town Jews were merchants and shopkeepers, they could remain only where the local economy was expanding. The second generation of Jews, born in the United States, had to seek opportunities elsewhere. According to Lois Fields Schwartz's history of Jewish Ligonier, there was a sharp decline in the Jewish population of Ligonier after 1925 for three main reasons. First, larger cities were more attractive to new immigrants for job opportunities. Second, children of Ligonier Jews went to schools in other cities, married, and remained there, again, because of greater opportunities. Finally, as older citizens of Ligonier passed away, their children did not want to continue their businesses. (According to Crumrin and Vanderstel, by the Great Depression, 80% of Indiana Jews lived in the five largest cities.) According to historian Amy Hill Shevitz, this pattern was consistent in small towns across the Midwest after World War II; Jewish communities declined because of "population loss, an aging population, [and] congregations merging or closing."

Primary sources show that Ligonier was a part of the "countercurrent" of decline explained by Weissbach. Ligonier newspaper articles show that at the turn of the century, the large congregation was still led by Rabbi Julius M. Magil, Ph.D., a respected scholar and religious leader. Meeting minutes show that Jacob Straus and Solomon Mier, founding members of the congregation, were still leading the congregation. The reception for Bar Mitzvah services in 1900 had over 130 attendees. However, late in 1900, Rabbi Magil left to be replaced by Rabbi Henry Englander. In 1905, Rabbi Englander also left. After this departure, Ahavath Sholom services were conducted by the rabbis of the temple in South Bend and other visiting rabbis for important holidays. Founding members Solomon Mier and Jacob Straus passed away in 1910 and 1914 respectively. Other prominent citizens from the first generation of Jewish Ligonier settlers were also passing. According to Schwartz, the congregation deeded their cemetery to the Ligonier Cemetery Association in 1912. According to a speech by Joseph Levine of the Indiana Jewish Historical Society, from 1922 to 1926, Rabbi Julius Mark served Ahavath Shalom congregation. However, a pamphlet from the confirmation services shows that in 1925 Rabbi Mark confirmed a class of only two young Jews.

While some secondary sources claim that services stopped in the 1920s, the meeting minutes and accompanying "Miscellaneous Materials" show that services were still held on High Holy Days into the 1930s and even 1940s. The Fort Wayne Journal Gazette reported, "Since 1932, the temple has either been empty or has housed Christian denominations." According to Levine, the congregation ceased using the temple in 1938. However, the meeting minutes of the congregation for April 10, 1942 and January 22, 1943 specifically note that the meetings were "held at the temple," with seven members attending the first and nine attending the second. Not until 1946 did the congregation meet elsewhere. The meeting minutes for September 10, 1946 show that the congregation gathered at the Wirk Garment Corporation as opposed to the temple. An invitation included in the collection of meeting minutes shows at least one meeting in 1947, but does not specify the location. The accompanying "miscellaneous materials" provides a list of sixteen members dated March 27, 1948. In 1949, the Hebrew Union College sent a letter to Ahavath stating that they would send student rabbis to officiate High Holy Days. In 1963, one elderly member, Leon Wertheimer recalled "As a gradual migration took place and the death of the elders there was a constant decrease in the number and at this time to the best of my knowledge there are but three Jewish families in Ligonier."

In 1975, the Indiana Jewish Historical Society dedicated the Abraham Goldsmith Memorial Room in the Ligonier Public Library with the purpose of "honoring and commemorating a group of Ligonier Jewish residents who left their mark on this community." In the 1980s, the Ligonier Public Library purchased the Ahavath Sholom building from the Trinity Assembly of God. Starting in 1989, the building was repurposed to house the Ligonier Historical Society, which remains there as of 2014. For more information on the continuing work to process the collection of the Ahavath Sholom congregation see http://ligoniertemple.blogspot.com/.