Location: Along Corporate Drive, just southeast of the River Ridge Development Authority at 300 Corporate Drive, Utica (Clark County), Indiana 47130

Installed 2017 Indiana Historical Bureau and Indiana Department of Transportation (Replaced marker 10.2016.1 WWII Army Ammunition Plant)

ID#: 10.2017.1

Text

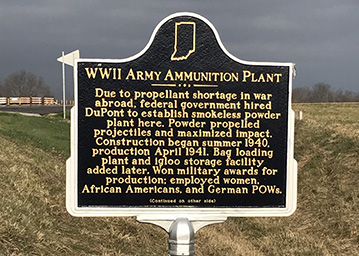

Side One

Due to propellant shortage in war abroad, federal government hired DuPont to establish smokeless powder plant here. Powder propelled projectiles and maximized impact. Construction began summer 1940, production April 1941. Bag loading plant and igloo storage facility added later. Won military awards for production; employed women, African Americans, and German POWs.

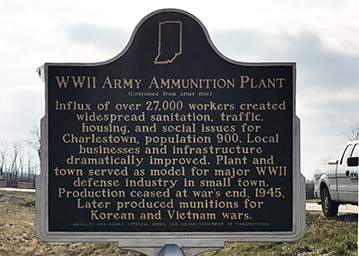

Side Two

Influx of over 27,000 workers created widespread sanitation, traffic, housing, and social issues for Charlestown, population 900. Local businesses and infrastructure dramatically improved. Plant and town served as model for major WWII defense industry in small town. Production ceased at war’s end, 1945. Later produced munitions for Korean and Vietnam wars.

Annotated Text

Due to propellant shortage in war abroad,[1] federal government hired DuPont to establish smokeless powder plant here.[2] Powder propelled projectiles and maximized impact.[3] Construction began summer 1940,[4] production April 1941.[5] Bag loading plant[6] and igloo storage facility added later.[7] Won military awards for production;[8] employed women,[9] African Americans,[10] and German POWs.[11]

Influx of over 27,000 workers[12] created widespread sanitation,[13] traffic, [14] housing,[15] and social issues[16] for Charlestown, population 900.[17] Local businesses and infrastructure dramatically improved.[18] Plant and town served as model for major WWII defense industry in small town.[19] Production ceased at war’s end, 1945.[20] Later produced munitions for Korean and Vietnam wars.[21]

[1] “Industry Piles Up 3 Billion Backlog of Unfilled Orders: British War and U.S. Defense Needs Point to Highest Upswing Since 1929,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 11, 1940, sec. 3, 10, Indiana State Library (ISL) microfilm; “Army Building: New du Pont Plant in Indiana Will Make 600,000 lb. of Powder a Day,” Life (January 20, 1941): 33, submitted by marker applicant; “A War Boom,” Nation’s Business 29, no. 5 (May 1941): 22, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; “Engineering and Construction,” The Du Pont Magazine 38, no. 2 (April-May 1944): 12-13, accessed Hagley Digital Archives; Steve Gaither and Kimberly L. Kane, The World War II Ordnance Department’s Government-Owned (GOCO) Industrial Facilities: Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, U.S. Army Materiel Command Historic Context Series, Report of Investigations, Number 3A (Geo-Marine, Inc., 1995): iii, 1,5, 8, submitted by marker applicant; “Milestones: 1937-1945,” U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1937-1945/lend-lease.

Although World War II commenced in September 1939 when Hitler invaded Poland, the U.S. did not officially enter the war until the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941. In the interim, the U.S. established an extensive ordnance system to provide desperately-needed war supplies to the Allied Powers, hoping in part to stall its own involvement in the war. Ordnance refers to any equipment that aides in combat, such as ammunition, propellant, armored vehicles and weapons.

According to Steve Gaither’s and Kimberly L. Kane’s comprehensive 1995 The World War II Ordnance Department’s Government-Owned (GOCO) Industrial Facilities: Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, existing U.S. ordnance arsenals could meet only about five percent of the Allies’ munitions needs at the outbreak of war. This contrasted greatly with Nazi Germany’s war resources, as the country had been producing material since the early 1930s. A 1944 article in The Du Pont Magazine aptly summarized the contrast, contending that:

Military powder production in this country was still at low ebb as late as Dunkirk and the ‘blitz’ of London. Hitler’s war machine, in process of building for a decade, was fully implemented and going strong when Americans were just beginning to embark on a national defense program. The size and urgency of that job then became more clear.

The Evacuation of Dunkirk in May 1940 and Fall of France in June greatly hastened U.S. efforts to construct ordnance plants and provide war material to the struggling Allied powers. This effort included the establishment of a smokeless powder plant in Charlestown, Indiana, referred to as the Indiana Ordnance Works #1 (IOW1). A 1941 Life article informed readers that modern warfare required 600,000 pounds of smokeless powder per day, resulting in a “frightening need for more powder plants.” Smokeless powder acted as the primary explosive propellant for various war ammunition (See footnote 3 for more about its production and purpose). Gaither and Kane assert that IOW1 was among the first ordnance plants established by the U.S. Ordnance Department to meet the need for war material in Europe. It operated as a Government-Owned Contractor-Operated (GOCO) facility, meaning that the federal government owned it and an outside company constructed and operated it. The establishment of the ordnance plant, and the addition of two others, transformed Charlestown from a small town into a booming defense city.

For an in-depth look at WWII ordnance needs and U.S. production of war material, see “Finances and the Effects of Lend-Lease,” in Constance McLaughlin Green, Harry C. Thomson and Peter C. Roots, The Ordnance Department: Planning Munitions for War in The US Army in WWII: The Technical Services (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1990).

[2] "Louisville to Get a New Powder Plant," The New York Times, July 13, 1940, 6, accessed ProQuest Historical Newspapers; "Contract is Signed for Big Powder Plant in Indiana to Produce 200,000 Pounds a Day," New York Times, July 18, 1940, 8, accessed ProQuest Historical Newspapers; “Building Awards Heavy: Decline from Last Week but Far Above Last Year,” New York Times, October 25, 1940, 42, accessed ProQuest Historical Newspapers; Walter A. Shead, “The Upheaval at Charlestown,” Part 3, Madison [IN] Courier, December 17, 1940, 5, accessed ISL microfilm; "Plant Cost Reaches 74 Millions," Charlestown Courier, January 9, 1941, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; Gertrude Springer, "Growing Pains of Defense," Survey Graphic 30, no. 1 (January 1941): 8, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; “The 139th Year,” The Du Pont Magazine 35, no. 3 (March 1941): 2-3, accessed Hagley Digital Archives; “A War Boom,” Nation’s Business 29, no. 5 (May 1941): 22, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Office of Production Management, Bureau of Research and Statistics, Listing of Major War Department Supply Contracts by State, June 1940 through September 1941 with October 1941 Supplement (Office for Emergency Management, Division of Information Washington, D.C.): 14, ISL Rare Books and Manuscripts; John E. Stoner and Oliver P. Field, Public Health Services in an Indiana Defense Community (Bloomington, IN: Bureau of Government Research, Indiana University, circa 1942): 49, ISL Rare Books and Manuscripts; “Engineering and Construction,” The Du Pont Magazine 38, no. 2 (April-May 1944): 12-13, accessed Hagley Digital Archives; “Military Explosives,” The Du Pont Magazine 39, no. 2 (May-June 1945): 9, accessed Hagley Digital Archives; Constance McLaughlin Green, Harry C. Thomson and Peter C. Roots, The Ordnance Department: Planning Munitions for War in The US Army in WWII: The Technical Services (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1990): 7; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 13-14.

In response to the propellant shortage in the war abroad, Congress passed funding for munitions production on July 1, 1940. The federal government partnered with businesses experienced in mass production to establish ordnance plants, known as Government-Owned Contractor-Operated (GOCO) collaborations. The Ordnance Department: Planning Munitions for War describes the effectiveness of the arrangement, stating “For procuring a great deal of ordnance, consequently, the best answer was found to be newly built government-owned contractor-operated plants—GOCO facilities. Thus the vast, rapid expansion was achieved, and government establishments, private facilities, and combinations of the two met demand.”

According to Boyden Sparkes, who wrote for The Saturday Evening Post, General Harris of the Army Ordnance Department called E.I. deNemours DuPont Co.’s Delaware office on June 17, 1940 to inquire about establishing a powder plant, “‘knowing the Du Ponts were more experienced in the manufacture of explosives than anyone else in the country’” (quoted in The Du Pont Magazine, 1944). Shortly thereafter, the company, researcher and producer of chemical products, began preparing their offices for the task. DuPont was awarded a war contract in July 1940 to work with the government to establish the IOW1 smokeless powder plant. A 1941 article in The Du Pont Magazine elaborated that while the federal government owned the plant, DuPont provided the “technical information, designs, and ‘know-how,’” receiving compensation on a fixed-fee basis. The company was also responsible for construction and overseeing operations at the plant.

According to 1941 articles in Survey Graphic and Nation’s Business, Charlestown was chosen as the site of the plant because of its inexpensive land, ready labor force, close proximity to railroads, and the massive water supply provided by the Ohio River, a requisite component in the production of smokeless powder. The Charlestown Courier noted in a January 16, 1941 article that Charlestown also met the requirement that the plant be removed from the country’s borders to avoid bombing or invasion. See footnotes 4, 5, and 6 for recruitment, construction, and production at IOW1 and the later-added bag-loading plant.

[3] Tenney L. Davis, The Chemistry of Powder and Explosives, vol. 1 (1941), vol. 2 (1943), 4, Chapter 6, accessed Archive.org; “Start Work Soon on Big Bag Plant,” Charlestown Courier, January 9, 1941, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “A War Boom,” Nation’s Business 29, no. 5 (May 1941): 22, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; "Powder Now Being Made in Quantity," Charlestown Courier, May 1, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; “Disposal of Big Plant’s Product Presents Problem,” Charlestown Courier, November 13, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; "Christmas Comes to a Great Defense Industry," Indianapolis Sunday Star, December 21, 1941, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; The Ordnance Department: Planning Munitions for War, 351; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 36.

According to The Ordnance Department: Planning Munitions for War, a smokeless and flashless propellant was necessary in combat because traditional smoke “would obscure gunners' vision and muzzle flash reveal the tank or battery position.” Thus, the Ordnance Department in WWII worked quickly to establish smokeless powder plants, including that of Indiana Ordnance Works in Charlestown. Gaither and Kane stated in their 1995 report that smokeless powder sent the “projectile through space and provided the power when the projectile contacted the target.” Tenney Davis elaborates in The Chemistry of Powder and Explosives that the powder, made from colloided nitrocellulose, acted as a “vigorous high explosive and may be detonated by means of a sufficiently powerful initiator. In the gun it is lighted by a flame and functions as a propellant.”

Charlestown’s IOW1 began producing smokeless powder in the spring of 1941. The plant also manufactured black powder in much lower quantities, which set off the smokeless powder. Once manufactured, workers weighed, bagged, and sealed powder at the adjacent Hoosier Ordnance Plant (HOP), a GOCO facility overseen by the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. An army spokesman in a Charlestown Courier article from November 13, 1941 noted that once workers prepped the powder it was transferred to “large munitions makers and powder dumps.”

See footnote 8 for IOW’s smokeless powder output and production awards. For more about the history and technical aspects of smokeless powder, see Chapter 6 in Tenney Davis’s The Chemistry of Powder and Explosives.

[4] “Defense: DuPont to Close Deal on 5,000 Acres,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 11, 1940, sec. 3, 7, ISL microfilm; “War Department Official Outlines Plans for Policing Charlestown Plant,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 21, 1940, ISL microfilm; “Powder Plant to Employ 4,000 Soon: Construction to Be Started Next Week,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 27, 1940, sec. 2, ISL microfilm; Advertisement, Carl Lutz & Son, “Ready Mixed Concrete: New Plant, New Trucks,” New Washington Courier, September 5, 1940, n.p., ISL microfilm; “Two Say Powder Plant Won’t Sully River Water,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 8, 1940, sec. 1, 9, ISL microfilm; Charles Griffo, “Ethridge Says Defense Program Brings $67,700,000 Income Here,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 12, 1940, sec. 2, ISL microfilm; Joe Hart, “Work at Charlestown Proceeds Under Guard,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 13, 1940, 1, ISL microfilm; Walter A. Shead, “The Upheaval at Charlestown,” Part 2, Madison [IN] Courier, December 12, 1940, 2, ISL microfilm; Gertrude Springer, “Growing Pains of Defense,” Survey Graphic 30, no. 1 (January 1941): 8, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; “282,000,000 Grants for Powder Plants,” New York Times, February 9, 1941, 24, accessed ProQuest Historical Newspapers; “A War Boom,” Nation’s Business 29, no. 5 (May 1941): 126-127, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Public Health Services in an Indiana Defense Community, 49; Compiled by Dorothy Riker, Indiana Historical Bureau, The Hoosier Training Ground: A History of Army and Navy Training Centers, Camps, Forts, Depots, and Other Military Installations Within the State Boundaries During World War II (Bloomington, IN: Indiana War History Commission, 1952): 358, accessed Fern Grove and Rose Island Resorts marker file; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 30, 80, 85-87, 107.

Sources conflict regarding the exact date construction began on IOW1. However, newspaper articles and secondary sources generally concur that construction was underway by September 1940. As a GOCO contractor, DuPont was responsible for the plant’s construction, operation and supply procurement. The company preferred to recruit labor locally, in southern Indiana and Louisville, Kentucky, but eventually a shortage of skilled laborers led to national recruitment. In their report, Gaither and Kane stated that while some recruits lacked skills, others were migrant construction workers who traveled the nation for jobs, and most “seemed to be earnest and industrious and felt they were doing their part to contribute to national defense.” According to the Nation’s Business, applicants were asked “where their sympathies lay in the European war, and whether they were sympathetic to any foreign isms.” Stringent security measures were applied to workers, requiring them to wear a button with their photograph to identify themselves.

Once construction commenced, thousands of workers poured into Charlestown, transforming it from a quiet farming town to a thriving worksite. An article in the September 13, 1940 Louisville Courier-Journal vividly described the scene, stating:

. . . farm houses were being wrecked. In that wreckage could be seen bruised and tangled masses of cultivated flowers, some in bloom, and imported shrubbery. The fields which this spring were planted in corn, soybeans and other crops were being subjected to the same treatment as if they had contained ragweed. Ears of golden yellow corn were being trampled underfoot by the workmen or ground under the wheels of motor cars.

A pamphlet published circa 1942 entitled Public Health Services in an Indiana Defense Community stated that shortly after construction began on IOW1 military events in the European theater necessitated expansion of the plant, eventually tripling its original capacity. Gaither and Kane aptly summarized that “original plans did not foresee the facility growing to the size it did. What at the beginning was to be a facility with two lines producing smokeless powder grew to first four lines, then six. Then the bag loading plant was added to the south side. These plans had changed over a matter of just a few months.” The Madison [IN] Courier noted in December 1940 that three shifts of men worked around the clock to meet the plant expansion. The September 13, 1940 Louisville Courier-Journal provided readers with a descriptive scene of the industrial work at IOW1:

Powerful machinery roared and brawny men, some 400 of them, toiled Thursday on the outskirts of Charlestown, Ind., in the initial phases of translating a maze of blue prints into a $25,000,000 Government powder plant. One giant machine, a power-driven crane, was busy picking up steel rails and placing them on previously laid cross ties with the apparent ease of a child laying toy building blocks.

For construction of the bag-loading Hoosier Ordnance Plant (HOP), see footnote 6. To learn about the closing of the plants, see footnote 20.

[5] Maurice Early, "The Day in Indiana," Indianapolis Star, December 19, 1940, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; “Operations Now Thot to Be Underway,” The Charlestown Courier, April 24, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; "Powder Now Being Made in Quantity," Charlestown Courier, May 1, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; The Hoosier Training Ground: A History of Army and Navy Training Centers, Camps, Forts, Depots, and Other Military Installations Within the State Boundaries During World War II, 359; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 36.

Secrecy about production, likely due to national security concerns, led to speculation about the exact date IOW1 first manufactured powder. The Charlestown Courier wondered on April 24, 1941 “Are they or are they not? While no official announcement has been made the consensus of opinion among outside observers is that they are making smokeless powder in the first two units of the big Charlestown plant.” The newspaper added that “several workmen are now seen with a new badge marked ‘Powder.’” Secondary sources, having greater access to plant records, concur that production began in April 1941. While sources from the period conflict regarding when workers first produced the powder, the Charlestown Courier reported that by May 1 the plant “sees the first production in quantity pass thru the final stages of solvent recovery and drying processes, finished for packing.” This aligns with Gaither and Kane, who stated in their report that by May 1941 IOW1 was capable of full production. The authors also note that the first production was 23 days ahead of schedule.

See footnote 8 for military awards received for production. See footnote 20 for the gradual reduction in production and eventual shut down of the plant. To learn about the powder-making and preparation process, see Chapter 3 of The World War II Ordnance Department’s Government-Owned (GOCO) Industrial Facilities: Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation.

[6] “Addition to Be Erected on Powder Plant Site: Bag-Loading Unit O.K.’d by U.S.,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 14, 1940, 2, ISL microfilm; "Make Plans for Work on Bag Plant," Charlestown Courier, January 2, 1941, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Start Work Soon on Big Bag Plant,” Charlestown Courier, January 9, 1941, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; "Powder Plant Pride of United States Army," Charlestown Courier, January 16, 1941, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; "Big Plant Ordered for Powder Loading," New York Times, January 26, 1941, 28, accessed ProQuest Historical Newspapers; “A War Boom,” Nation’s Business 29, no.5 (May 1941): 128, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; “Women Pick up Speed in Loadings Silk Powder Bags,” Charlestown Courier, September 4, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; "Christmas Comes to a Great Defense Industry," Indianapolis Sunday Star, December 21, 1941, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 8, 45, 46, 58-59, 62, 65, 73, 76; “Powder Worker,” Powder Horn (no date): cover page, submitted by marker applicant.

As construction began on IOW1 in September 1940, an Associated Press dispatch from Washington announced the addition of a bag-loading powder plant at Charlestown. The Louisville Courier-Journal stated that the new plant, dubbed the Hoosier Ordnance Plant or Works (HOP), would be responsible for “weighing and packing in silk bags of smokeless powder charges to be used in certain types of heavy artillery.” According to a January 9, 1941 Charlestown Courier article, the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company signed a contract with the War Department to establish a plant near IOW1, which would produce rubberized silk bags and fill them with smokeless powder. This type of plant was referred to as a LAP facility because it loaded, assembled and packed powder. Gaither and Kane stated that the LAP process involved “preparation of the cloth by washing and drying, cutting the pieces for the bags, printing the charge numbers on the bags, and sewing up the finished product” (58).

Construction of HOP began February 1941 and, according to Gaither and Kane, construction employment peaked at 14,891 in August. An article in the Nation’s Business described how the additional plant impacted the area, which was “already reeling under the feet of 18,000 workers, along came new munitions workers, next door to Indiana Ordnance. . . It will, Goodyear officials say, be able to bag more powder than any plant now in existence.” Operations officially began on September 2, 1941 and by December all eight loading lines were running, producing so efficiently that by March 1942 the Ordnance Department requested the plant lower output (Gaither and Kane, 65, 73).

Women comprised the majority of employees at the bag-loading plant, whereas men primarily worked at IOW1. At HOP, women oversaw powder cutting machines, fabricated bags, and loaded them with powder. For more about women’s contributions, see footnote 9.

NOTE: While not included in the marker text, a double-base rocket powder plant was partially-constructed in Charlestown at the end of the war. The plant greatly expanded the Charlestown ordnance facility, brought thousands more workers to the town and may have utilized POWs for construction. Information and sources regarding the plant can be found below.

"'Charlestown Area Studies Fate of War Industries," Indianapolis Star, August 20, 1945, 1, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Sigrid Arne, “Charlestown Workers Go Home Leaving ‘Ghost Town’ Behind,” Richmond Palladium, October 4, 1945, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; John E. Stoner and Oliver P. Field, Public Schools in an Indiana Defense Community (Bloomington, IN: Bureau of Government Research, Indiana University, 1946): 61, ISL Rare Books and Manuscripts; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 8, 76-77.

In addition to a smokeless powder plant and bag-loading plant, the federal government located a double-base rocket powder plant in Charlestown in late 1944, known as Indiana Ordnance Works 2 (IOW2). The addition doubled the size of the ordnance facility, which included IOW1, HOP, IOW2 and igloo storage facilities. According to a 1945 Indianapolis Star article, IOW2 drew about 20,000 construction workers to Charlestown, creating an additional population boom and mass housing problem. Gaither and Kane reported that the plant manufactured a small amount of powder before cancelling construction in August 1945 at the conclusion of the war. The Indianapolis Star article noted that the plant was only a quarter complete before workers were laid off in 1945.

German prisoners of war were brought to the area to assist with construction of IOW2. See footnote 11 for more information about the POWs.

[7] "Planning Board Named to End Chaos in Charlestown Boom," Indianapolis News, October 19, 1940, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; “Clark County in Review,” Charlestown Courier, May 29, 1941, 4, ISL microfilm; “Clark County in Review,” Charlestown Courier, May 29, 1941, 4; R. Christopher Goodwin & Associates, Inc., Army Ammunition and Explosives Storage During the Cold War (1946-1989) (May 2009), Chapter 3, p. 2, 7, 8; “Women Pick up Speed in Loadings Silk Powder Bags,” Charlestown Courier, September 4, 1941, front page, ISL microfilm; Charles G. Griffo, “Rebirth of an Arsenal,” Indianapolis Star Magazine, June 29, 1952, 6-8, ISL Clippings Files-Ordnance; “Council Hears Report on Possible Use of Rocket Plant for Shelters,” Charlestown Courier, December 7, 1961, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 9, 38, 47, 49-50, 62, 66; R. Christopher Goodwin & Associates, Inc., “Indiana Army Ammunition Plant,” Historic Context for Department of Defense Facilities World War II Permanent Construction (May 1997), 279.

The volatility of smokeless powder required stringent storage precautions. The powder manufactured at IOW1 was stored in HOP ammunition magazines before being loaded and packed by HOP employees and shipped out. The HOP magazines were called “igloos” because of their shape. According to R. Christopher Goodwin’s 2009 study, after January 1941 the Ordnance Department required “that all ammunition storage. . . be the arched concrete igloo magazine.”

Goodwin noted in his 1997 report that specially designed buildings are described as “barrel-shaped igloo structures of reinforced concrete covered with earth on three sides and located in a separate area and spaced about 450’ apart.” Strict safety regulations came about as a result of a disastrous series of explosions at a Navy Ammunition Depot in 1926.

According to Gaither and Kane, 177 igloos were constructed at the HOP plant; they occupied almost three-quarters of the 5,000-acre HOP facility. A reporter for the Charlestown Courier, May 29, 1941, described the smaller igloos as the “size of good sized grocery store.” The structure was designed such that “in the event of disaster the thick walls prevent damage to adjacent buildings [sic] the force of the explosion going skyward.”

For more information see: R. Christopher Goodwin & Associates, Inc., Army Ammunition and Explosives Storage During the Cold War (1946-1989) published May 2009 for the U.S. Army Environmental Command.

[8] “Star to Be Added to Plant ‘E’ Flag,” Powder Horn 3, no. 3 (no date): [3?], submitted by applicant; "Charlestown Area Studies Fate of War Industries," Indianapolis Star, August 20, 1945, 11, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; “Army-Navy ‘E’ Award Termination Sees Award Granted to 5% of Eligible Plants,” War Department, Bureau of Public Relations, December 5, 1945, accessed Allison marker file; Carl Lewis, “This Bubble Didn’t Burst,” Indianapolis Star Magazine, October 10, 1948, 8-10, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Charles G. Griffo, “Rebirth of an Arsenal,” Indianapolis Star Magazine, June 29, 1952, 6-8, ISL Clippings Files-Ordnance; Letter, Robert P. Patterson, Under Secretary of War, to Walter S. Carpenter, Jr., President, E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Company, in “Indiana Ordnance Works Excellence of Performance Program, August 10, 1942,” accessed Indiana Memory Digital Collections; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 8, 43, 76.

According to a 1948 Indianapolis Star Magazine article, the ordnance plant produced more than one billion pounds of smokeless powder during WWII, nearly as much as the “total volume of military explosives made for the United States in World War I.” In August 1942, the military nationally recognized IOW1’s production and safety records, conferring upon the plant the Army-Navy “E” Award. The plant newsletter Powder Horn informed readers that the military awarded qualifying ordnance plants every six months, based on factors such as overcoming production issues, avoiding stoppages, safety, and excellent management.

U.S. Under Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson wrote to DuPont president Walter S. Carpenter, Jr. that the award:

symbolizes your country’s appreciation of the achievement of every man and woman in the E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Company at the Indiana Ordnance Works. Accorded only to those organizations which have shown exceptional performance in fulfilling their tasks, it consists of a flag to be flown above your plant, and a lapel pin which each individual within your organization may wear as a sign of distinguished service to his country.

Gaither and Kane stated that HOP was among few GOCO facilities to win the award every year of operation during WWII. According to a joint Army-Navy release from the War Department in December 1945, over 4,000 war production facilities won the award during the war, but this number represented only 5% of the estimated war plants in the country.

For more information about the need for smokeless powder, see footnote 1. To learn about production at IOW1, see footnote 5.

[9] “Start Work Soon on Big Bag Plant,” Charlestown Courier, January 9, 1941, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; Charlestown Courier, January 16, 1941, 4, accessed Newspapers.com; "Charlestown Planning New $1,000,000 School, Recreation and Health Center," Indianapolis Star, May 4, 1941, 1, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; “Women Pick up Speed in Loadings Silk Powder Bags,” Charlestown Courier, September 4, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; Margaret Christie, “Women Do Their Part for Defense,” Indianapolis Star, September 28, 1941, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Frank S. Adams, “Women in Democracy’s Arsenal,” New York Times, October 19, 1941, SM10, accessed ProQuest Historical Newspapers; "Christmas Comes to a Great Defense Industry," Indianapolis Sunday Star, December 21, 1941, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Manufacturing Committee and Indiana Economic Council, Preliminary Report, “Hoosiers at Work: What They Do, What They Make, What of the Future?” (November 1944): 22, ISL Rare Books and Manuscripts; Indianapolis Star, March 6, 1944, 1, ISL microfilm; “Powder Worker,” Powder Horn (no date): cover page, submitted by applicant; Max Parvin Cavnes, The Hoosier Community at War (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1961): 46.

WWII defense needs quickly brought women into the labor force, particularly later in the war as men left factories to enter into combat. The New York Times reported on October 19, 1941 that women “are beginning to play an important part in the armament plants of the nation,” including painting planes, covering oil lines and packing powder bags. The article asserts that women surpassed male workers in “finger dexterity,” “powers of observation,” and “superior traits in number memory.”

As with the nation, Indiana began employing women en masse at munitions factories. By 1944, the Indianapolis Star reported that one-third of Indiana factory workers were women and that while industrial work was once considered “unsuitable for women . . . this view has been abandoned since employers have found that women can and have been willing to adjust themselves to practically any type of labor if given the opportunity.” Women were hired in large numbers at Charlestown’s ordnance facility. The Powder Horn reports that women at IOW, previously mail runners and lab technicians, replaced men as powder cutting machine attendants. The bag-loading plant known as HOP employed 3,200 workers by December 1941, most of whom were women, who sewed bags and packed them with powder.

Max Parvin Cavnes’ The Hoosier Community at War noted that by 1942 so many women worked at the Charlestown plants that the town had to rapidly expand child care facilities, enlarging the community center nursery at Pleasant Ridge Project. Women experienced other obstacles to employment in Charlestown, as the Charlestown Courier reported that women were prohibited from riding the “four special trains bringing employes [sic] to the Powder Plant. They have to find some other way to get to their jobs here.”

The Indianapolis Star also reported about “trailer wives,” who felt they contributed to defense efforts by relocating their families to ordnance towns, where their husbands found employment. The article described these women as a “gallant band who ‘follow construction’ in order to keep the family life being lived as a unit and not subject themselves and their husbands to the hardships of separation.”

[10] Louise Gilbert, “Community Organization Solves Play Problem in Defense Area,” Public Welfare in Indiana (June 1942): 6, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Indiana State Defense Council and Indiana State Chamber of Commerce, “Job Opportunities for Negroes,” Pamphlet no. 4 (January 1943): 3, 13, 16, ISL Rare Books and Manuscripts; “Negroes Will Not Occupy Trailers,” Charlestown Courier, June 14, 1944, 1, Newspapers.com; “Houses Reserved for Operators at New Rocket Plant,” Charlestown Courier, June 7, 1945, 1, Newspapers.com; Max Parvin Cavnes, The Hoosier Community at War, 145; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 102, 104, 107, 113-115.

Much like women in WWII, defense needs partially opened the labor force to African Americans. A questionnaire from the Indiana State Defense Council sent to employers reported that from July 1, 1941 to July 1, 1942 the state experienced a net increase of 82% in factors reporting black employment. It stated that “most of the gains were made in the manufacturing field” and that “the bottleneck of defense training opportunities for Negroes has been broken.”

Gaither and Kane cited difficulty locating data about African American workers at Charlestown’s ordnance facility in their 1995 report. IHB staff experienced similar problems locating records, but confirmed that African Americans worked at Charlestown’s ordnance facility. According to Gaither and Kane, African Americans originally worked at IOW1 in janitorial and unskilled fields. However, by the end of 1942, after the “first tension of the labor shortage,” the payroll listed 876 black workers at the plant in various roles, such as chemists, plant laborers, and plant operators (115).

Former plant employees stated in interviews that they witnessed little or no segregation, but that separate restrooms may have existed at one time (Gaither and Kane, 115). However, housing and schooling for African Americans was segregated and often in poor condition. Due to protests by some white residents regarding mixed housing units, a section of 130 units was separated for black workers by a 300 foot wide area (104). The Hoosier Community at War cites a 1942 Louisville Courier-Journal article about the deplorable state of Clark County African American schools, particularly in Charlestown Township, stating that grade school students:

were broken out in a rash of goose pimples yesterday morning as they shivered at their antiquated desks. . . . A not unbitter wind whistled thru broken window panes and thru cracks in the walls of the sixty-five year old frame building as twenty-three students . . . huddled together and with stiffened fingers signed up for a year of ‘education.’

The boom afforded limited employment opportunities for African Americans outside of the plant, despite earlier employer prejudice, which often barred them from working at local Charlestown businesses.

[11] Sandy Wood, “Army’s Suggestion to Work Nazi Prisoners at Charlestown Plant Brings 3-Way ‘Deadlock,’” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 12, 1945, 4, ISL microfilm; Old Timer, “Clark County in Review,” Charlestown Courier, May 24, 1945, 8, Newspapers.com; Charlestown Courier, May 31, 1945, 8, Newspapers.com; Charles G. Griffo, "'Boom' Is Dead at Charlestown, But Powder Men Take End Gayly," Indianapolis Star, August 19, 1945, 5, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 4, 76-77, 115-119.

Approximately 1,000 German prisoners of war were transferred to Charlestown to supplement construction of the rocket powder plant (IOW2) (See footnote 6 for information about the plant). While Gaither and Kane stated that the prisoners were moved to the area by May 20, 1945, newspaper articles reported that the POWs were not transferred until May of that year.

A Louisville Courier-Journal article published on May 12, 1945 noted that Army, War Production Board, and union officials were conflicted about bringing the German prisoners to work at the plant. However, on May 24 the Charlestown Courier reported that 500 of the expected 1,000 POWs arrived to help construct the rocket powder plant, describing them as healthy-looking teenagers. The Indianapolis Star reported on August 19, 1945 that the POWs had left the plant (as the war had ended) and returned to Fort Knox and other camps where they were “obtained.” Newspapers located by IHB staff did not report on their contributions and Gaither and Kane contended it was “doubtful that the POWs contributed directly to construction.”

[12] U.S. Census Bureau, 1940 Census of Population, Vol. 1 Number of Inhabitants, Ch. 4 Georgia-Iowa, Indiana Table 4 Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions, 340, ISL State Data Center; Walter A. Shead, “The Upheaval at Charlestown,” Part 2, Madison [IN] Courier, December 12, 1940, 2, ISL microfilm; “The First Year . . . From Farmland to Finished Powder,” Powder Horn 1, no. 2 (1941): 7, accessed Indiana Memory Digital Collections; Charlestown Courier, March 13, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; “Builders Get Brief Rest; Off 3 Days,” Charlestown Courier, May 29, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; “Women Pick up Speed in Loadings Silk Powder Bags,” Charlestown Courier, September 4, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; “New Census Will Greatly Increase Gas Tax Refund,” Charlestown Courier, November 13, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; “Engineering and Construction,” The Du Pont Magazine 38, no. 2 (April-May 1944): 24, accessed Hagley Digital Archives; Sigrid Arne, “Charlestown Workers Go Home Leaving ‘Ghost Town’ Behind,” Richmond Palladium, October 4, 1945, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 33.

The influx of construction and production workers for the IOW1, HOP, and IOW2 ordnance plants created enormous problems for the town of Charlestown, with a population of 939 (1940 Census). Actual numbers of Charlestown residents and workers varied greatly based on construction and production schedules throughout the war.

While the number of workers descending on the Charlestown area grew above 30,000 by the spring of 1941, the population increase in the town was much smaller. Many workers commuted from other parts of the state and the Louisville area rather than settling in Charlestown, which largely accounted for the discrepancy between employment and population figures.

According to Gaither and Kane, construction workers at the powder plant peaked in May 1941 at 27,520; this figure doesn’t include about 5000 construction workers at the HOP; nor does it include production workers at IOW#1. According to Gaither and Kane, construction work at the HOP plant was busiest in August 1941 with 14,891 at the job site.

Thus, while occupancy rates were often in flux, it is evident that the flood of workers dramatically changed the town, summarized by the Madison [IN] Courier in December 1940, which stated that the increase of inhabitants:

presents major problems of housing, of food supply, of health and sanitation and of transportation. The state agencies which have control over all these factors have moved into Charlestown and are working in conjunction with the state co-ordinator to bring order out of chaos and to give all protection, both to the local community and to the new population. The lack of facilities for adequate housing is reflected in a survey conducted by the state board of health.

In 1941, Charlestown successfully petitioned the U.S. Census Bureau to recount the population because of the mass influx, hoping to qualify as a city in order to take advantage of the gas tax. The updated census listed the town’s population at 2,457, up from 939. This likely did not take into account the thousands who temporarily inhabited the town for work. Many migrant workers rented rooms, commuted from nearby towns, and lived in trailers, cars and any enclosed structure. The arrival of these thousands of workers created massive sanitation, traffic, housing and social issues. For information about how the drastic increase in inhabitants impacted the small town, see footnotes 13, 14, and 15.

[13] Maurice Early, “The Day in Indiana,” Indianapolis Star, October 1, 1940, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; “Planning Board Named to End Chaos in Charlestown Boom,” Indianapolis News, October 19, 1940, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Walter A. Shead, “The Upheaval at Charlestown,” Part 1, Madison [IN] Courier, December 11, 1940, 4, accessed ISL microfilm; Walter A. Shead, “The Upheaval at Charlestown,” Part 2, Madison [IN] Courier, December 12, 1940, 2, accessed ISL microfilm; Gertrude Springer, “Growing Pains of Defense,” Survey Graphic 30, no. 1 (January 1941): 44, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Charlestown Courier, January 16, 1941, 4, accessed Newspapers.com; Charlestown Courier, March 6, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; “Weekly Programs on Health Subjects,” Charlestown Courier, March 13, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; “No Trailers in Unlicensed Town Camps,” and “City Jail and Fire Station Is Condemned,” Charlestown Courier, May 15, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; “Board Wants to Recount Population, Charlestown Courier, May 22, 1941, 4, ISL microfilm; “City-Size Job for a Village,” Engineering News-Record 127, no. 1, July 3, 1941, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Margaret Christie, “Women Do Their Part for Defense,” Indianapolis Star, September 28, 1941, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; John E. Stoner and Oliver P. Field, Public Health Services in an Indiana Defense Community, 7, 27, 28, 42-44, 49, accessed ISL Rare Books and Manuscripts; Louise Gilbert, “Community Organization Solves Play Problem in Defense Area,” Public Welfare in Indiana (June 1942): 5, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Max Parvin Cavnes, The Hoosier Community at War, 17; John D. Barnhart and Donald F. Carmony, Indiana From Frontier to Industrial Commonwealth (Indianapolis, Indiana Historical Bureau, 1979): 490.

The rapid growth of Charlestown created immense housing and sanitation issues. In Indiana From Frontier to Industrial Commonwealth, John D. Barnhart and Donald F. Carmony contend that Charlestown “suffered quickly the growing pains of a boom town as thousands of newcomers moved in and overtaxed sewage and water systems, and overflowed the schools, churches, and housing facilities.” In December of 1940, Walter A. Shead wrote a three-part series in the Madison [IN] Courier about Charlestown’s pre-IOW1 sanitation and water facilities. He noted that “only in the past few years did the city fathers see the need of a public water supply, the town folks depending on private wells and cisterns.” He elaborated that the town previously had no sewage system and that the WPA was just beginning to construct one. John E. Stoner and Oliver P. Field also studied Charlestown’s facilities during the boom in their 1942 Public Health Services in an Indiana Defense Community. They stated that as a result of plant activity the town began imposing health and garbage regulations, having had no systematic trash or human waste disposal program. Additionally, a 1941 Survey Graphic article reported that the town severely lacked public restrooms and had “no public control of overcrowding in lodging or boarding houses.”

The lack of sanitary accommodations in the boom town induced fear of epidemics. Stoner and Field reported “The dangers to health flowing from a congestion of workers drawn from north and south and east and west, eating and sleeping under the most elementary conditions, crowded into inadequate quarters and serviced by water, milk, and sanitary facilities designed for a small community can hardly be exaggerated” (7). The rapid establishment of trailer camps exacerbated these fears, housing hundreds of transient workers in close proximity. Shead stated that the State Board of Health required owners to register their camps and “comply with the state regulations as to sanitation and water supply in an effort to prevent an outbreak of malaria and typhoid.” The Charlestown Courier reported on May 15, 1941 that even the town jail was condemned and closed by the State Board of Institutions for sanitation reasons.

Town and state officials worked to improve facilities and inform inhabitants about public health. Gaither and Kane reported that by July 1, 1940 a 12-month immunization program was underway, vaccinating townspeople for smallpox and tuberculosis. The Indianapolis News noted in October 1940 that the State Board of Health undertook a survey about the public’s health needs. The board began routinely exhibiting films about hygiene, communicable diseases, and other health subjects to educate the public and forestall epidemics. Additionally, an article in Public Welfare in Indiana stated that the board established a venereal disease clinic and dispatched nurses to the town. Accounts vary regarding the success of these measures, as a flu epidemic materialized at the powder plant and the town experienced more dysentery, typhoid fever, and tuberculosis than the rest of the state. However, most records concede that, considering the massive population boom, close living quarters, and inadequate sanitation facilities, the rate of disease remained fairly low.

See footnote 18 to learn about the improvements made to town infrastructure and facilities as a result of the population boom.

[14] Maurice Early, "The Day in Indiana," Indianapolis Star, October 1, 1940, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Maurice Early, “One Day in Indiana,” Indianapolis Star, December 19, 1940, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Walter A. Shead, “The Upheaval at Charlestown,” Part 3, Madison [IN] Courier, December 17, 1940, 5, accessed ISL microfilm; Gertrude Springer, “Growing Pains of Defense,” Survey Graphic 30, no. 1 (January 1941): 44, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; “Plan Modern Paving Here,” Charlestown Courier, February 6, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; “16,000 Autos Counted On Highway 62,” Charlestown Courier, February 13, 1941, front page, ISL microfilm; Old Timer, “Clark County in Review,” Charlestown Courier, February 13, 1941, 4, ISL microfilm; “City-Size Job for a Village,” Engineering News-Record 127, no.1, July 3, 1941, 55, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 77, 79, 92-93, 97.

According to Gaither and Kane, when work began on the ordnance plants Indiana Road 62 was the only paved road in Charlestown. Thus, the influx of thousands of workers created widespread traffic issues, especially as Charlestown lacked traffic police. An article in the October 1, 1940 Indianapolis Star described the scene, reporting that “workmen and those seeking work jam the streets and the atmosphere is one of carnival.” The newspaper added in December of that year that when the afternoon work shift ended workers were stuck in traffic at the parking lot gate for an hour and a half. A Survey Graphic article noted in 1941 that “the one effect of the plant construction that seems to be hitting everyone in Clark County is traffic. Workers are driving daily as many as sixty miles to their jobs, and the narrow two-lane roads are wholly unequal to the load.”

To ease the burden, Indiana State Road 62 was converted into a four-lane highway and the WPA paved town streets (Gaither and Kane, 92-93, 97). The Engineering News-Record reported in July 1941 that the State Police established a sub-office in the area and provided six employees to control traffic. Additionally, an increase in railroad and bus lines to Charlestown reduced traffic jams, often transporting workers up from Louisville. The Charlestown Courier boasted that “Charlestown is rapidly becoming an important terminal for Southern Indiana bus lines bringing workers to the Powder Plant. Lines are now operating buses three times daily.”

[15] Advertisement, “Dupontonia Sub—Division,” New Washington [IN] Courier, August 29, 1940, n.p., ISL microfilm; “Our Sermonette,” New Washington Courier, September 19, 1940, 1, ISL microfilm; Maurice Early, “The Day in Indiana,” Indianapolis Star, October 1, 1940, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Earl Richert, “Charlestown to be ‘Guinea Pig’ for Nation,” Indianapolis Times, October 4, 1940, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; “Planning Board Named to End Chaos in Charlestown Boom,” Indianapolis News, October 19, 1940, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Richard Lewis, “Charlestown’s Boom ‘Pattern’ Not As of Yore,” Indianapolis Times, November 8, 1940, 14, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Walter A. Shead, “The Upheaval at Charlestown,” Part 1, Madison [IN] Courier, December 11, 1940, 1, accessed ISL microfilm; Walter A. Shead, “The Upheaval at Charlestown,” Part 2, Madison [IN] Courier, December 12, 1940, 2, accessed ISL microfilm; Phillips J. Peck, “Charlestown Fairly Reeks with Wealth,” The Gary-Post Tribune, December 18, 1940, 4, ISL microfilm; Gertrude Springer, “Growing Pains of Defense,” Survey Graphic 30, no. 1 (January 1941): 44, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; W.C. Miller, “Industrial Giant’s Too Big for Charlestown; Officials Keep Vice Out Between Headaches,” Indianapolis Sunday Star, January 12, 1941, 16, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; “Army Building: New du Pont Plant in Indiana Will Make 600,000 lb. of Powder a Day,” Life (January 20, 1941): 34, submitted by applicant; Old Timer, “Clark County in Review,” Charlestown Courier, February 6, 1941, 4, ISL microfilm; “Contract to Construct 75 U.S. Houses” and “May Not be Able to Use Houses Soon,” Charlestown Courier, May 15, 1941, ISL microfilm; “Begin Work on Housing Project Here,” Charlestown Courier, May 29, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; “Agree for New Census,” Charlestown Courier, July 17, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; Old Timer, “Clark County in Review,” Charlestown Courier, September 4, 1941, 6, ISL microfilm; “More Applicants for Apartments than Available,” Charlestown Courier, September 4, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; Margaret Christie, “Women Do Their Part for Defense,” Indianapolis Star, September 28, 1941, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Stoner and Field, Public Health Services in an Indiana Defense, 49, 50; Cavnes, The Hoosier Community at War, 26-40; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 83-84, 86, 94.

Housing the thousands of workers that poured into Charlestown for employment at the ordnance facility became one of the town’s most immediate problems. According to a December 1940 Gary-Post Tribune article, Charlestown had approximately 235 existing homes and one hotel so crowded that “you can’t get a room for love or money.” The extreme housing shortage led transient workers to inhabit a variety of dwellings, well-documented by local sources at the time. A Charlestown Courier article from February 1941 reported “It may have been a hen house, wash house, wood house, garage or what have you for lo, these many years, but the minute it has been insulated, windows and chimney installed and Powder Plant workers have moved in and hung lace curtains, it becomes a guest house.” Indianapolis newspapers reported that new arrivals lived in trailers, cars, chicken coops, barns, lean-tos and even the town jail. Margaret Christie noted in the Indianapolis Star that “men and women have been living in literally anything that could shelter them. . . . Needless to say, every room for miles around is occupied. Doubly and trebly more. At the peak many beds never get cold. They were slept in in shifts.”

Charlestown residents ultimately benefited from the overcrowding, as they rented and sold houses, rooms, and residential structures at a considerable profit. A Survey Graphic article reported that houses which typically rented for $10-$12 per month began renting for $20-$30 and that “every habitable shack and shed in and around Charlestown has been patched up and rented for all the traffic will bear.” Outsiders also sought to profit from the boom, as real estate developers migrated to the town hoping to provide accommodations for transient workers. Gaither and Kane stated that private builders remodeled houses and even developed a subdivision known as DuPontonia.

Charlestown, ill-equipped to meet such urgent and massive housing demands, sought federal funding for housing projects. According to a May 15, 1941 Charlestown Courier article, the town received a federal housing grant from the FHA for 75 housing units. The newspaper reported in July of that year that the units would be completed shortly, but would still lack sewer and water, and that if “all were now ready for occupancy they would fail to make a dent in the demand for housing here." Despite overwhelming need, housing expansion moved at a moderate pace, as town residents, real estate agents and the federal government worried that a rapid and permanent expansion could lead to a ghost town at the conclusion of war. Trailer camps provided a large, short-term solution to the housing problem, providing hundreds of transient workers and families with housing in an estimated 17-21 camps. In their Public Health Services in an Indiana Defense Community, Stoner and Field convey the magnitude of the camps, describing “big luxurious palace-like trailers, poor little make-shift trailers, plain ordinary trailers, but trailers everywhere.” See footnote 13 for sanitation concerns associated with these camps.

[16] Walter A. Shead, “The Upheaval at Charlestown,” Part 1, Madison [IN] Courier, December 11, 1940, 1, ISL microfilm; A.E. Minzghor, A Du Pont Employee, “Protests Tax on Trailers,” Charlestown Courier January 2, 1941, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Opposition to $10 Tax on Trailers,” Charlestown Courier, January 2, 1941, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Charlestown Trailer Colony Protests Proposal to Levy $10 Location Tax,” Indianapolis Star, January 6, 1941, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Letter to the Editor, Ernest H. Orman, Charlestown Courier, January 9, 1941, 4, accessed Newspapers.com; “Wilson Promises Facilities for New School Children,” Charlestown Courier, September 4, 1941, 1, ISL microfilm; Margaret Christie, “Women Do Their Part for Defense,” Indianapolis Star, September 28, 1941, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Stoner and Field, Police Administration in an Indiana Defense Community, 7; Stoner and Field, Public Schools in an Indiana Defense Community, 8, 41; Charles G. Griffo, “Charlestown Looks to U.S. to Ease ‘Boom,’” Indianapolis Star, February 11, 1951, 3, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 99, 102-104.

Prior to the establishment of the ordnance facility, Charlestown was a small town, consisting of primitive sanitation facilities, unpaved roads and very few local businesses. In a letter to the editor of the Charlestown Courier, resident Ernest H. Orman described the town as “a beautiful, quiet, clean place in which to live. Each individual took the greatest pride in helping to keep the town neat and lovely.” Walter Shead reported how thousands of migrant workers impacted the town in the Madison [IN] Courier, stating that “Native folks in Charlestown are a little dazed, for they hardly know just what to make of this hub-bub which has come to shake the even tenor of their ways, a manner of life which has endured for more than a century.”

The arrival of workers en masse from around the country taxed local businesses, infrastructure, and sanitation facilities, generating tension between local residents and transient workers regarding who should shoulder the burden. The Indianapolis Star noted that transient workers strongly opposed a proposed $10 tax on trailer camp dwellers to meet these new demands. Migrant workers often felt unwelcome in Charlestown and reasoned they already contributed a great deal of their income to the town. The January 2, 1941 Charlestown Courier documented the conflict, as local resident Orman lamented the escalating cost of city government due to increased needs for police, fire, garbage, and street services. He contended “we believe the trailer owners will fully appreciate the situation when they know the facts and will cooperate, as I have found them unusually . . . fair minded.” Plant employee A.E. Minzghor wrote from the perspective of a migrant in the same issue that:

Charlestown should welcome us, if for no other reason but the one that at least 25% of our wages are spent here. . . . We are here in the interests of our Country and to earn an honest living which, in this land of ours, is every citizen’s right. Charlestown has looked down on us so called Du Ponters, but as yet have not refused to take our money.

While locals were not typically hostile to migrant workers, they sought to differentiate themselves, labeling the newcomers “du Ponters” and their children “powder children.” Residents hoped to curtail the potential for drunkenness, gambling, and prostitution with the influx of workers. Sources differ regarding how successful locals were at maintaining the town’s quiet, conservative lifestyle. However, a town police officer recollected in a 1951 Indianapolis Star article that during the period people were “sleeping on sidewalks and drunks were all over the place.” While locals struggled to adapt to the major changes the town underwent, migrant workers resented the implication that locals considered them “‘trailer trash,’” as Margaret Christie reported in the Indianapolis Star. Christie stated “they most emphatically are not, and deeply do they resent that appellation. It is that sort of divergence of feeling and expression that sets them apart from the townspeople, among whom they perforce must dwell for long periods of time.”

In addition to tension between locals and migrant workers, white inhabitants conflicted with African Americans who migrated to Charlestown for employment. Gaither and Kane asserted that the housing of African Americans resulted in protest and some white workers threatened to quit their jobs. See footnote 10 for more information about the conflict between white residents and African Americans.

[17] "Planning Board Named to End Chaos in Charlestown Boom," Indianapolis News, October 19, 1940, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Walter A. Shead, “The Upheaval at Charlestown,” Madison [IN] Courier, December 11, 1940, Part 1, 4, accessed ISL microfilm; U.S. Census Bureau, 1940 Census of Population, Vol. 1 Number of Inhabitants, Ch. 4 Georgia-Iowa, Indiana Table 4 Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions, 340; U.S. Census Bureau, 1950 Census of Population, Vol. 1 Number of Inhabitants, Ch. 5 Florida-Indiana, Indiana Table 6 Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions, 12-14.

The 1940 Census of the United States listed 939 residents living in Charlestown. The establishment of the ordnance plant rapidly brought between 25,000 and 40,000 workers to the Charlestown area, creating a boom town. An Indianapolis News article from October 1940 noted “The growing pains of Charlestown, the Clark county town boomed by the du Pont-federal munitions plant under construction there, are being felt in the Statehouse.” While thousands of migrant workers left the town at the end of the war in August 1945 (see footnote 20), the 1950 Census of the United States shows that the town maintained a larger population than before the war at 4,786 residents.

See footnote 12 for estimates regarding the number of transient workers who came to Charlestown during the period. Footnotes 13-16 describe how the massive workforce impacted the small town.

[18] Maurice Early, “The Day in Indiana,” Indianapolis Star, October 1, 1940, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Earl Richert, “Tripling of Powder Plant at Charlestown Now Rumored,” Indianapolis Times, October 19, 1940, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Richard Lewis, "Charlestown's Boom 'Pattern' Not As of Yore," Indianapolis Times, November 8, 1940, 14, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Walter A. Shead, “The Upheaval at Charlestown,” Part 1, Madison [IN] Courier, December 11, 1940, 4, ISL microfilm; Phillips J. Peck, “Charlestown Fairly Reeks with Wealth,” The Gary-Post Tribune, December 18, 1940, 4, ISL microfilm; Maurice Early, "The Day in Indiana," Indianapolis Star, December 19, 1940, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; “Bunk House is Popular,” Charlestown Courier, January 9, 1941, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “A War Boom,” Nation’s Business 29, no. 5 (May 1941): 127, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; “Clark County in Review,” Charlestown Courier, May 15, 1941, 4, ISL microfilm; “WPA Street Paving Work Gets Started,” Charlestown Courier, May 15, 1941, front page, ISL microfilm; “New Fronts for 3 Stores,” Charlestown Courier, May 29, 1941, front page, ISL microfilm; “Clark County in Review,” Charlestown Courier, October 2, 1941, 6, ISL microfilm; Stoner and Field, Public Health Services in an Indiana Defense Community, 62; Louise Gilbert, “Community Organization Solves Play Problem in Defense Area,” Public Welfare in Indiana (June 1942): 5, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Stoner and Field, Public Schools in an Indiana Defense Community, 44; Carl Lewis, “This Bubble Didn’t Burst,” The Indianapolis Star Magazine, October 10, 1948, 9-10, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown.

Footnotes 13-16 detail problems created by the establishment of the ordnance facility in Charlestown.

The massive strain on Charlestown’s businesses, infrastructure, schools, and sanitation facilities ultimately led to their permanent improvement. In 1940, Richard Lewis reported in the Indianapolis Times that the rapid industrialization not only improved facilities, but created jobs that reduced the county’s welfare load. Lewis elaborated that “The roar of a growing industrial city, streams of traffic moving through the streets, trailers parked on every vacant piece of ground, the skeletons of new houses above the fields have remade life in Charlestown.”

Promoters and real estate agents quickly flocked to the town, recognizing an opportunity to profit from the boom. A 1941 Nation’s Business article explained “people arrived to start everything from cheeseburger stands to honky-tonks.” While new business blossomed, local businesses expanded and improved structures. A Gary-Post Tribune article from December 1940 described the town as “fairly reeking with prosperity” and noted that the ordnance facility brought more money and people to the town than residents could have imagined. According to the article, the town originally had two restaurants, but by December 1940 eight “eating places” existed and customers nearly had to “fight their way in to the counter.” Shead reported in the Madison [IN] Courier that grocery, drug, dry good, and hardware stores increased stocks and ordered new items to meet the demand. Privies were installed on street corners to accommodate the prospective employees.

Additionally, housing and accommodations greatly improved during the period. The Gary-Post Tribune stated the only hotel in town offered 16 rooms, but doubled in capacity by the end of 1940. Prior to the plant, Charlestown had approximately 235 houses (footnote 15), but by late 1941 Charlestown established two major housing projects, Pleasant Ridge and Jennings Trace, with a combined 900 units (Star Magazine). Along with housing, the town’s sanitation facilities improved, as the WPA sped up work on Charlestown’s first sewage system. The October 2, 1941 Charlestown Courier reported that the town received funding to improve the local school system, noting excitedly that “There is no stopping Charlestown now. We are on our way. Watch the new homes and business houses go up!”

Local roads and transportation exponentially improved, as the Indianapolis Times reported that the Highway Commission resurfaced and improved miles of road, and that newly-appointed state police directed traffic. The Gary-Post Tribune noted that “board members now meet three and four times a week and they have adopted such novelties as parking regulations, zoning law, building code and set up a town planning board.” The improvement and expansion of nearly every facet of the town can be attributed to the establishment of the WWII ordnance facility. Public Schools in an Indiana Defense Community summarized in 1946 that “the coming of the munitions plants, therefore, may be viewed as the incident which precipitated the movement for a [public school] building program.”

[19] “Payroll Boost of 37.7 Pct. Predicted for Louisville Area,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 11, 1940, sec. 3, ISL microfilm; “White, Blue Collars—7,000 Strong—Surround du Pont Hiring Office,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 4, 1940, sec. 2, ISL microfilm; Earl Richert, "Charlestown to be 'Guinea Pig' for Nation," Indianapolis Times, October 4, 1940, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; "Powder Plant Pride of United States Army," Charlestown Courier, January 16, 1941, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Opportunity for Model City Here,” Charlestown Courier, January 23, 1941, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; Old Timer, “Clark County in Review,” Charlestown Courier, March 13, 1941, 4, ISL microfilm; “A War Boom,” Nation’s Business 29, no. 5 (May 1941): 128, 130, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Louise Gilbert, “Community Organization Solves Play Problem in Defense Area,” Public Welfare in Indiana (June 1942): 5, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Lynn W. Turner, “Indiana in World War II: A Progress Report,” Indiana Magazine of History 52, no. 1 (March 1955): 9, accessed Indiana Magazine of History, Indiana University ScholarWorks.

Although newspaper and magazine articles frequently credited the Charlestown ordnance facility as the country’s first or most productive WWII smokeless powder plant, IHB generally avoids the use of subjective and superlative terms such as “first,” “best,” and “most.” Such claims are often not verifiable and/or require extensive qualification to be truly accurate. However, it is evident that the plant was among the most productive smokeless powder plants during WWII, having received military awards for production excellence.

Local and national sources described the Charlestown facility as a “guinea pig,” “test case,” and “model city” for other munitions factories in small towns. The Indianapolis Times described Charlestown in October 1940 as “sort of a yardstick. It is the first little town in the nation at which a major national defense plant has been located—the Government’s $25,000,000 smokeless powder factory.” An article in Public Welfare in Indiana stated the Charlestown facility provided an ideal test because it had already experienced many of the problems large ordnance factories would encounter. In May 1941, the Nation’s Business asserted that the President hoped to use Charlestown as a model for “defense industry boom towns.” More research should be undertaken to confirm this statement, as it is outside the scope of this project.

[20] “Rocket-Plant Construction Is Suspended: New Building Also Halted at Hoosier Ordnance Works; Order Affects 20,000 Workers,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 13, 1945, 8, ISL microfilm; Sandy Wood, “Rocket-Powder Plant Closing Is Blow to Charlestown,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 14, 1945, Sec. 2, ISL microfilm; Charles G. Griffo, "'Boom' Is Dead at Charlestown, But Powder Men Take End Gayly," Indianapolis Star, August 19, 1945, 1, 5, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Sigrid Arne, “Charlestown Workers Go Home Leaving ‘Ghost Town’ Behind,” Richmond Palladium, October 4, 1945, n.p., ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 8, 43, 73, 77, 80.

Munitions production gradually wound down with termination of the two-front war, which concluded first on May 7, 1945 with German surrender and then on August 14, 1945 with Japan’s informal agreement to surrender (formally surrendering on September 2, 1945). Gaither and Kane cite an entry in the plant diary on August 14, 1945 documenting the termination of 1,000 DuPont employees. The following day the commanding officer at the plant received a message from the Field Director of Ammunition Plants directing the end of production at IOW1, with the exception of two types of smokeless powder. Charles Griffo reported in the Indianapolis Star on August 19 that the personnel reduction at IOW1 and HOP “was forecast long ago and the rolls were reduced gradually, the reduction beginning soon after V-E Day. Combined personnel of the two plants was 19,000 workers.” Griffo stated that HOP seemed to have shut down before the gradual closing of IOW1. (See Gaither and Kane for details about plant closings).

The Richmond Palladium noted that after reductions “scarcely a wheel turned, or a hammer fell. Now there are just a few thousand ‘running out’ the powder which was in process, and putting the whole installation in weather-tight conditions.” Gaither and Kane reported that a skeleton crew engaged in this minimal production until October 5. After this, a handful of employees decontaminated the plant and put parts in layaway. According to Gaither and Kane, the rocket powder plant (IOW2) received orders to cancel construction work on August 11, 1945. Construction ceased entirely on August 13; within two weeks 15,328 construction employees had been dismissed and POWs transferred. The October 4, 1945 Richmond Palladium reported that construction of IOW2 was cancelled when it was only 25% complete and that “men from Washington are rushing details for a mammoth sale which will dispose of $12,000,000 worth of plumbing, brick, steel, lumber, machinery, electrical fixtures.”

Griffo reported on the exodus resulting from the closing of the complex, stating “every day since last Tuesday has been moving day as thousands of construction men and many powder production workers left the plants for other jobs or ‘any job,’” via car, bus, railroad and “thumb.” He noted that the boom town “is dying with the same gusto with which it was born.” The Richmond Palladium described Charlestown folding up “like an Arabian tent village,” as trailer caravans departed and workers returned to various states across the nation. The newspaper reported that the abrupt exodus shocked local residents, who worried about maintaining their postwar economy. According to the newspaper, a “trickle” of new residents soon arrived, including veterans and their families. Gaither and Kane concluded that ultimately locals adapted to the postwar conditions, although boom town activity returned during the Korean War period. See footnote 21 to learn about munitions production for the Korean and Vietnam wars.

[21] “Speculate on Reopening of Powder Plant, “Charlestown Courier, July 13, 1950, 1, ISL microfilm; “Precaution is Being Taken at Big Plant,” Charlestown Courier, August 24, 1950, 1, ISL microfilm; "DuPont to Run Indiana Plant," Indianapolis Times, January 9, 1951, 10, ISL Clippings Files, Ordnance; Charles G. Griffo, “Charlestown Looks to U.S. to Ease ‘Boom,’” Indianapolis Star, February 11, 1951, 3, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; Staff Writer, "Charlestown Mayor Views Arsenal as Key to Future," Indianapolis Star, December 10, 1951, 25, ISL Clippings Files, Cities and Towns-Charlestown; "Contract to Reopen Charlestown Plant," Indianapolis News, January 9, 1952, 12, ISL Clippings Files-Ordnance; “Witten Will Open Trailer Court,” Charlestown Courier, April 3, 1952, 1, Newspapers.com; “Powder Line Set to Start Here June 1,” Charlestown Courier, May 15, 1952, 1, Newspapers.com; Charles G. Griffo, “Rebirth of an Arsenal,” Indianapolis Star Magazine, June 29, 1952, 6-8, ISL Clippings Files-Ordnance; “Will Start Taking Applications on October 1, to Employ 25 Right Away,” Charlestown Courier, August 24, 1961, 1, Newspapers.com; “Applications for Arsenal to be Accepted Each Thursday,” Charlestown Courier, August 31, 1961, 1, Newspapers.com; “Arsenal Swamped by Job Seekers,” Charlestown Courier, August 31,1961, 5, Newspapers.com; “The Babbling Brook,” Charlestown Courier, August 31, 1961, 1, Newspapers.com; "Arsenal Near Charlestown to Be Reactivated," Indianapolis News, September 19, 1961, 24, ISL Clippings-Ordnance; Jack Hester, “The Babbling,” Charlestown Courier, October 26, 1961, 1, Newspapers.com; Gaither and Kane, Indiana Army Ammunition Plant Historic Investigation, 8, 131-133.

The Korean War commenced on June 25, 1950. According to the July 13 Charlestown Courier, speculation “increases daily” regarding the ordnance plant’s reopening, as some former WWII employees reportedly received letters asking if they would like to return. According to Gaither and Kane, at the conclusion of WWII, the arsenal was to “be ready to go into operation on a substantial scale within 120 days and to store War Department materials.” This proved beneficial, as the arsenal was reactivated in the Korean War period, with DuPont and Goodyear again signing contracts to assist in the manufacture and preparation of smokeless powder. According to a 1952 article in the Indianapolis Star Magazine, in early 1951 the Defense Department ordered partial reactivation of the Charlestown ordnance facility. The Indianapolis News reported on January 9, 1952 that DuPont signed a contract with the Army to resume operations at Charlestown, which “suffered a critical unemployment situation” after WWII. The Indianapolis Star Magazine asserted that the rehabbing activity in Charlestown was reminiscent of the town’s WWII construction era, reporting “Full security is in operation. . . . Workmen are everywhere. DuPont supervisory workers, who haven’t seen each other for years, meet again.”

The ordnance facility later produced material for the Vietnam War, when it was reactivated August 23, 1961 to produce and pack powder, as well as debag, cross blend and dry propellant used to load charges. The Charlestown Courier reported in August of 1961 that “there is some discussion about whether it was reactivated to curb unemployment in the area” or due to “necessary military preparedness.” Regardless, applications flooded in after the announcement, including many sent from those who had worked at the plant in the WWII and Korean War eras. Gaither and Kane state that in August 1963 the facility was renamed the “Indiana Army Ammunition Plant.” They note that Vietnam era production began at IOW1 in January 1962, growing steadily in the 1960s and decreasing in 1970 with the de-escalation of conflict in Asia.

Keywords

Business, Industry, and Labor; Military; Buildings and Architecture