James Whitcomb Riley Home

Location: 528 Lockerbie St. Indianapolis (Marion County, Indiana) 46202

Installed 2018 Indiana Historical Bureau and the Riley Children’s Foundation

ID#: 49.2018.1

Text

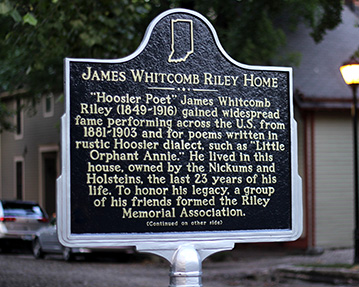

Side One:

“Hoosier Poet” James Whitcomb Riley (1849-1916) gained widespread fame performing across the U.S. from 1881-1903 and for poems written in rustic Hoosier dialect, such as “Little Orphant Annie.” He lived in this house, owned by the Nickums and Holsteins, the last 23 years of his life. To honor his legacy, a group of his friends formed the Riley Memorial Association.

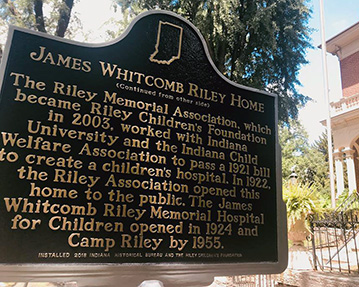

Side Two:

The Riley Memorial Association, which became Riley Children’s Foundation in 2003, worked with Indiana University and the Indiana Child Welfare Association to pass a 1921 bill to create a children’s hospital. In 1922, the Riley Association opened this home to the public. The James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Hospital for Children opened in 1924 and Camp Riley by 1955.

Annotated Text

Side One:

“Hoosier Poet”[1] James Whitcomb Riley (1849-1916)[2] gained widespread fame performing across the U.S. from 1881-1903[3] and for poems written in rustic Hoosier dialect,[4] such as “Little Orphant Annie.”[5] He lived in this house, owned by the Nickums and Holsteins, the last 23 years of his life.[6] To honor his legacy, a group of his friends formed the Riley Memorial Association.[7]

Side Two:

The Riley Memorial Association, which became Riley Children’s Foundation in 2003,[8] worked with Indiana University and the Indiana Child Welfare Association to pass a 1921 bill to create a children’s hospital.[9] In 1922, the Riley Association opened this home to the public.[10] The James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Hospital for Children opened in 1924[11] and Camp Riley by 1955.[12]

[1] “An Evening with J.W. Riley, the Hoosier Poet, Humorist and Dialectic Reader” Program from Riley Performances, circa 1881, James Whitcomb Riley Collection, IUPUI Digital Collections, Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis, accessed http://indiamond6.ulib.iupui.edu/cdm/ref/collection/JWRiley/id/607; “James Whitcomb Riley: The Hoosier Poet,” (Greenfield, Indiana) Hancock Democrat, February 9, 1882, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; Advertisement for Riley Performance in Antrim N.H., broadside, 1883, James Whitcomb Riley Collection, IUPUI Digital Collections, accessed http://indiamond6.ulib.iupui.edu/cdm/ref/collection/JWRiley/id/559; Advertisement for Riley Performance at the YMCA, n.d., circa 1880s, broadside, James Whitcomb Riley Collection, IUPUI Digital Collections, accessed http://indiamond6.ulib.iupui.edu/cdm/ref/collection/JWRiley/id/560; Advertisement, Indianapolis News, October 14, 1893, 9, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Carmen Bliss, “Mr. Riley’s Poetry,” Atlantic Monthly 82: 491 (September 1898): 424; “Boniface Riley,” (Franklin) Evening Star, March 29, 1906, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Books That Sold Best,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 07, 1901, 24, accessed Newspapers.com; “Riley’s Birthday To Be Celebrated,” Greenfield Republican, September 26, 1912, 6, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Many to Celebrate James Whitcomb Riley’s Birthday on Oct. 7; How the Hoosier Poet Sprang into Fame 35 Years Ago,” Hammond Times, October 7, 1913, 4, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Riley’s Birthday,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 7, 1912, 5, accessed Newspapers.com; “’Hoosier Poet’ Star in Centennial Film,” Liberty (Union County) Express, June 9, 1916, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; James Whitcomb Riley, James Whitcomb Riley’s Complete Works (Indianapolis & New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1916), accessed IUPUI Digital Collections, http://indiamond6.ulib.iupui.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/JWRiley/id/5334/rec/109; Elizabeth J. Van Allen, James Whitcomb Riley: A Life (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999) 183; “James Whitcomb Riley,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/james-whitcomb-riley

After Riley began his lecture tours across the country, newspapers, magazines, broadsides, and advertisements began labelling him “the Hoosier Poet.” For example, a broadside advertising a Riley performance leads with the large-type headline “Hoosier Poet;” see it here. A similar advertisement referred to Riley as “The Hoosier Poet, Humorist, and Dialect Reader;” see it here. Also, the author and/or editor of an autobiography that appeared in the 1900 collection Eccentricities of Genius titled the essay “James Whitcomb Riley – “The Hoosier Poet.”

A search of Hoosier State Chronicles for references to Riley as “Hoosier Poet” yields over three hundred results, the earliest from 1882; the same search in Newspapers.com yields over three thousand results, the earliest also from 1882. In one example, drawn from these thousands of articles, on February 9, 1882, the (Greenfield, Indiana) Hancock Democrat featured a large engraving of Riley on the front page along with the headline “The Hoosier Poet.” On March 29, 1906, the Franklin Evening Star ran a cartoon drawing of Riley labelling him “the Hoosier poet.” On September 26, 1912, the Greenfield Republic reported on a large celebration of the birthday of James Whitcomb Riley, the beloved Hoosier Poet.” Likewise, an October 7, 1913 headline in the Hammond Times read: “Many to Celebrate James Whitcomb Riley’s Birthday on Oct. 7; How the Hoosier Poet Sprang into Fame 35 Years Ago.” Most of the obituaries that appeared after Riley’s death in 1916, referred to him as “the Hoosier poet,” as well as articles published into the present day.

Riley’s book became best sellers. In 1893, the Bowen-Merrill (later Bobbs-Merrill) Company announced in an advertisement in the Indianapolis News that “various volumes” by Riley were selling “at the rate of about forty thousand copies a year.” In 1900, the Indianapolis News reported on the publisher: “The first notable success of the firm as publishers was with the poetical works of James Whitcomb Riley. Thousands and thousands of volumes of Mr. Riley’s poetry have been sold, and he is to-day at the zenith of his popularity. Over sixty thousand volumes of his works are sold every year . . .” In 1901, the Bobbs-Merrill Company reported that Riley’s Farm Rhymes “has had an enormous sale.” In 1912, the Philadelphia Inquirer stated: “Judged by popularity, by the sale of his works, he is easily the leasing American poet alive today.” Upon his death in 1916, newspapers across the country ran a syndicated obituary that noted: “His books sold steadily from the first, and his royalties amounted to a very respectable little fortune.”

Van Allen wrote that while poetry anthologies normally “had a limited readership,” Riley’s works “went through a number of editions” during his lifetime and “sales figures for Riley’s books surpassed those of his idol,” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. For example, the 1916 edition of James Whitcomb Riley’s Complete Works, published by Bobbs-Merrill was already in its tenth edition. See it here. Van Allen writes that a fire at Bowen-Merrill (later Bobbs-Merrill) destroyed files containing sales figures for Riley before 1900 but that the publisher sold over 2.5 million copies of his work during the centennial of the poet’s birth. According to the Poetry Foundation, Riley was “one of his day’s best-selling writers.”

[2] U.S. Bureau of Census, Seventh Census (1850), Schedule 1, Center Township, Hancock County, Indiana, Roll M432_149, page 174B, Image 25, accessed AncestryLibrary; U.S. Bureau of Census, Ninth Census (1870), Schedule 1, Center Township, Hancock County, Indiana, Roll M432_149, page 174B, Image 25, accessed AncestryLibrary; James Whitcomb Riley to Elizabeth Kahle, November 22, 1879, James Whitcomb Riley to John Taylor, November 29, 1879, Interview with Chris Martindale, n.d., in Van Allen, 142, 152 (f.n. 249), 154 (f.n. 8); “James Whitcomb Riley,” Medical Certificate of Death, July 22, 1916, Indianapolis, Indiana, Indiana Archives and Records Administration; “Indiana Will Pay Tribute to Riley: Poet’s Body Will Lie in State at the Capitol at Request of Governor,” Indianapolis Star, July 24, 1916, 1, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; “James Whitcomb Riley,” Medical Certificate of Death, July 22, 1916, Indianapolis, Indiana, Indiana Archives and Records Administration, Roll 13, accessed AncestryLibrary; “James Whitcomb Riley,” photograph of grave, accessed FindAGrave.com; “Indiana Will Pay Tribute to Riley: Poet’s Body Will Lie in State at the Capitol at Request of Governor,” Indianapolis Star, July 24, 1916, 1, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; “Sorrowing Thousands to View Body of Riley,” Indianapolis News, July 24, 1916, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

James Whitcomb Riley was born October 7, 1849. The 1850 census shows one-year-old Riley living with his parents in Center Township, Hancock County, Indiana. Henry Eitel, Riley’s brother-in-law later confirmed his birthdate to the Indianapolis Star.

In 1870, Riley was still living with his parents in Greenfield, Hancock County, Indiana. While he had been traveling back and forth from Greenfield to Indianapolis for some time, he moved to the Hoosier capital in November 1879 to work at the Indianapolis Journal, according to an interview with Journal editor and personal letters from Riley to friends. He does not appear in the Indianapolis City Directory, however, until 1882, listed as a writer at the Indianapolis Journal, and living in room 21 Vinton block.

He died July 22, 1916 and lay-in-state at Indiana State House. Thousands of people came to the statehouse to pay their respects. Riley is buried at Crown Hill Cemetery.

[3] “An Evening with J.W. Riley, the Hoosier Poet, Humorist and Dialectic Reader” Program from Riley Performances, n.d. [circa 1881], James Whitcomb Riley Collection, IUPUI Digital Collections, Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis, accessed http://indiamond6.ulib.iupui.edu/cdm/ref/collection/JWRiley/id/607 ; “Mr. Riley’s Boston Success”, Indianapolis Journal, January 5, 1882, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; “Mr. Riley in Boston,” Indianapolis Journal, January 7, 1882, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; “James Whitcomb Riley,” (Hillsboro, Ohio) Highland Weekly, December 27, 1882, 5, accessed Newspapers.com; “Bill Nye to Chicago Tribune,” reprinted “Bill Nye on Hotels,” Altoona (Pennsylvania) Times, November 24, 1886, 3, accessed Newspapers.com; Advertisement, Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Daily Independent, October 30, 1886, 4, accessed Newspapers.com; “Bill Nye to the Boston Globe” reprinted in “Lecturing Tour of a Poet,” Alpena (Michigan) Argus, May 4, 1887, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Riley’s Success,” Indianapolis Herald, December 3, 1887, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; “Bill Nye, The Greatest Living Humorist, and James Whitcomb Riley, The Hoosier Poet,” Program from Nye and Riley Performance, January 27, 1890, James Whitcomb Riley Collection, IUPUI Digital Collections, Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis, accessed http://indiamond6.ulib.iupui.edu/cdm/ref/collection/JWRiley/id/597; “Riley Will Make Another Reading Tour,” Indianapolis Journal, September 6, 1903, 28, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

Letters cited by his biographer Van Allen and in the volume Letters of James Whitcomb Riley, show that he signed with the Redpath Lyceum Bureau (later Redpath Booking Agency) in Chicago for the 1881-2 season. While Riley had been performing around Indiana since the 1870s, the booking agency allowed him to take his program to a national audience. For example, by 1882, the press was praising his Boston appearances and, by 1887, his New York appearances.

The James Whitcomb Riley digital collection hosted by the IPUI University Library contains several programs and advertisements for Riley’s live performances throughout his career. For example, one pamphlet, published at the beginning of Riley’s touring career advertised “his new programme to all lecture associations of his native state for 25-00 including all expenses” and quoted from Indiana newspapers praising his performances in Indianapolis in 1879.

From 1886-1890 when Riley toured with humorist Bill Nye, newspapers printed Nye’s tales from their travels. According to an exhibition on Riley curated and digitized by the Lilly Library at Indiana University:

Riley's popularity soared in the 1880s with performances almost nightly by 1889. .. Riley's program alternated poetry, character sketches and prose stories. He often appeared with other noteworthy writers and entertainers such as Eugene Field, Mark Twain, George Cable, Robert J. Burdette, and Bill Nye. . . In 1890 Riley decided to stop touring fulltime and devote his energies to his manuscripts and book publishing. Although he never again lectured as extensively after 1890, Riley continued to appear on the winter lyceum circuit. He lectured during the 1892-1893, 1893-1894, 1896-1897, 1897-1898, 1898-1899, 1900 and 1903 seasons.

On September 6, 1903, the Indianapolis Journal reported on Riley’s history of touring and announced his last tour. Read the full article. According to the Journal:

On his earlier tours Mr. Riley frequently gave as many as six readings a week. But he will never do that again. The coming tour he will give about four readings a week, spending the remainder of the time resting. He expects to devote about three months to the work . . . The greatest tour James Whitcomb Riley ever made was in 1889-90 with Bill Nye . . . The tour consisted of about 140 readings . . . Many weeks readings were given six successive nights after long days of hard, tiresome travel . . . Never again will Mr. Riley undertake as extensive a tour as this one.

While he continued to perform public readings, he ceased touring after 1903.

[4] Hamlin Garland, “Real Conversations: A Dialogue Between James Whitcomb Riley and Hamlin Garland,” McClure’s Magazine, 2:3, (New York, February, 1894), 228; “Riley’s New Book,” Indianapolis News, October 6, 1900, 16, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Advertisement, Indianapolis News, December 21, 1916, 7, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Dale B. J. Randall, “Dialect in the Verse of ‘The Hoosier Poet,’” American Speech 35:1 (February 1960): 36-50, accessed JTOR; “James Whitcomb Riley,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/james-whitcomb-riley

In 1894, Riley discussed his use of dialect with the writer Hamlin Garland, explaining that he began using the format while working at the Indianapolis Journal. Riley explained:

I was a sort o’ free-lance-could do anything I wanted to. Just about this time I began a series of ‘Benjamin F. Johnson’s poems. They all appeared with editorial comment, as if they came from an old Hoosier farmer from Boone County. They were so well received that I gathered them together in a little parchment volume, which I called ‘The Old Swimmin’ Hole and ‘Leven More Poems, my first book.

He continued:

I’ve written dialect in two ways. One, as the modern man, bringing all the art he can to represent the way some other fellow thinks and speaks; but the Johnson poems are intended to be like the old man’s written poems, because he is supposed to have sent them to the paper himself. They are representations of written dialect, while the others are representations of dialect, as manipulated by the artist.

In an October 6, 1900 article, the Indianapolis News used a full page to discuss Riley’s new book of poems “Home-Folks” which featured several excerpts from poems using “Hoosier dialect” and a general discussion of the poet’s use of dialects. Referring to earlier volumes of “dialect and serious poems” such as Rhymes of Childhood and Green Fields and Running Brooks, the Indianapolis News stated that the poems were “all informed and permeated with the very spirit of the Hoosier soil from which they sprung.” The article continued: “The poet reverts to his favorite dialect, the every-day speech of the Hoosier countryman, which he has done so much to make familiar to the world.” In a 1916 advertisement, the Bobb-Merrill Company featured four volumes of Riley’s work, noting that they contained poems “both serious and in dialect.” These were Neighborly Poems, Rhymes of Childhood, Home-Folks, and Morning. According to the Poetry Foundation, “full of sentiment and traditional in form, his work features rustic subjects who speak in a homely, countrified dialect.”

For a scholarly analysis of Riley’s use of “Hoosier dialect,” see: Dale B. J. Randall, “Dialect in the Verse of ‘The Hoosier Poet,’” American Speech 35:1 (February 1960): 36-50, accessed JSTOR.

[5]James Whitcomb Riley, The Orphant Annie Book (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merill Company Publishers, 1908), James Whitcomb Riley Collection, IUPUI Digital Collections, Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis, accessed http://indiamond6.ulib.iupui.edu/cdm/ref/collection/JWRiley/id/827; James Whitcomb Riley, “Little Orphant Annie,” Victor Records, 1912, National Jukebox, Library of Congress, accessed http://www.loc.gov/jukebox/recordings/detail/id/2688/; “. . . And Touch the Universal Heart.": The Appeal of James Whitcomb Riley, online exhibition, Lilly Library, Indiana University, accessed http://www.indiana.edu/~liblilly/riley/exhibit.htm.

According to an exhibition on Riley curated and digitized by the Lilly Library at Indiana University:

The poem we familiarly call "Little Orphant Annie" was first printed in the Indianapolis Journal on November 15, 1885 as "The Elf Child." It appeared under that title in Character Sketches, The Boss Girl, a Christmas Story, and other Sketches published by the Bowen-Merrill Company in 1886 . . . When next published Riley altered the title to "Little Ophant Allie," but a typesetting error turned Allie into Annie. Riley contacted his publisher about a correction, but upon being informed that the edition was selling extremely well, he decided to leave the error intact.

Several stanzas of the poem feature “Hoosier dialect,” such as:

An’ one time a little girl ‘ud allus laugh an’ grin,

An’ make fun of ever’one, an’ all her blood an’ kin;

An’ onc’t, when they was “company," an’ ole folks was there,

She mocked ‘em an’ shocked ‘em, an’ said she didn’t care!

Listen to James Whitcomb Riley read his poem “Little Orphant Annie,” recorded in Indianapolis on April 29, 1912.

[6] “Riley, James Whitcomb,” R. L. Polk’s Indianapolis City Directory for 1891 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co.), 655, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; “Riley, James Whitcomb,” R. L. Polk’s Indianapolis City Directory for 1892 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co.), 687, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; “Riley, James Whitcomb,” R. L. Polk’s Indianapolis City Directory for 1893 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co.), 717, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; James Whitcomb Riley to the “Lockerbies,” John Nickum, Charlotte Nickum, Charles Holstein, and Magdelena Holstein, letter, 1893, James Whitcomb Riley Collection, IUPUI Library Digital Collections, accessed http://indiamond6.ulib.iupui.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/JWRiley/id/339/rec/40; “Riley, James Whitcomb,” R. L. Polk’s Indianapolis City Directory for 1894 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co.), 671, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; “Like the Hoosiers,” Indianapolis Journal, September 29, 1894, 8, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Riley, James Whitcomb,” R. L. Polk’s Indianapolis City Directory for 1895 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co.), 674, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; “Holstein, Charles L.,” R. L. Polk’s Indianapolis City Directory for 1895 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co.), 432, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; U.S. Bureau of Census, Twelfth Census (1900), Schedule 1, Central Township, Marion County, Indiana, Roll 389, Page 1B, Enumeration District 0102, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; “Nickum, John R.,” R. L. Polk’s Indianapolis City Directory for 1902 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co.), 766, accessed AncestryLibrary; U.S. Bureau of Census, Thirteenth Census (1910), Center Township, Marion County, Indiana, Roll 389, Page 1B, Enumeration District 0102, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Magdelena Holstein, “James Whitcomb Riley’s Life in Lockerbie Street,” 1916, manuscript, James Whitcomb Riley Collection, IUPUI Library Digital Collections, accessed http://indiamond6.ulib.iupui.edu/cdm/ref/collection/JWRiley/id/393; Sanborn Map Company, Indianapolis Sanborn Map #50, 1887, vol. 2, IUPUI Digital Collections, accessed http://indiamond6.ulib.iupui.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/SanbornJP2/id/369/rec/8; William E. Baist, Indianapolis Baist Atlas Plan #6, 1908, IUPUI Digital Collections, accessed http://indiamond6.ulib.iupui.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/SanbornJP2/id/2247/rec/2.

Indianapolis City Directories show John R. Nickum living on Lockerbie Street since the 1860s, but the house was numbered 26, until the turn of the century when the house was numbered 528.

Riley had been friends with the Nickums and Holsteins for some time as seen in several letters available in the James Whitcomb Riley Collection. View an 1893 letter from Riley where he refers to them as the “Lockerbies.” While the 1893 and 1894 City Directory lists Riley as a boarder at the Denison Hotel, Riley was living at Nickum/Holstein home at 26 Lockerbie Street at least by 1894. The Indianapolis Journal reported September 29, 1894 on his return home after a vacation: “The news of his return home spread rapidly among his numerous friends and the parlors at his residence, No. 26 Lockerbie street, were crowded with callers during the evening.”

The 1895 City Directory lists him as a boarder at 26 Lockerbie; John R. Nickum was listed as having a home at 26 Lockerbie. Sanborn and Baist Atlas Maps of the neighborhood show that the Nickum home on Lockerbie was changed from house number 26 to house number 528 but is the same home. Census records show that Riley was the guest of John and Charlotte Nickum and their daughter and son-in-law Magdelena (Maggie) and Charles Holstein.

Maggie Holstein wrote that after vacationing with the family in French Lick, Riley’s luggage was delivered to the Holstein home instead of the Denison. Charles Holstein then invited Riley to stay; Riley insisted on paying to board and stayed until his death in 1916.

[7] “To Start Fund for Riley Memorial,” Indianapolis News, September 11, 1916, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “’Indiana’ To Be Shown for the Riley Memorial,” Indianapolis News, September 13, 1916, 4, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Articles of Incorporation of the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association, Filed April 9, 1921, transcribed in in Report of F.E. Schortemeier, Secretary, James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association, for the Year Ending December 31, 1921, James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association Minutes vol. 1, 1920-1926, transcription copy in IHB marker file.

After Riley’s death in 1916, several of his friends formed the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association. The Association directors for 1916 included prominent Indiana men such as writers Booth Tarkington, George Ade and Meredith Nicholson, publisher William C. Bobbs, architect Evans Woolen, doctor and politician Carleton B. McCulloch, and businessman and philanthropist William Fortune, among others.

The Association was active raising funds “to provide an adequate memorial to James Whitcomb Riley” as early as September 1916, when, in cooperation with the Indiana Historical Commission, they showed the centennial motion picture “Indiana,” which featured a clip of Riley surrounded by children.

On August 21, 1917, the Indianapolis News reported that the Association decided that their permanent memorial to Riley would take the form of a children’s hospital. The same article reported that “prominent businessmen” of Indiana had already taken steps toward raising money for a $2,000,000 endowment fund, including organizing a committee to work out the details. These prominent men included Josiah Lilly, James Allison, and Frank Ball, among others. The newspaper reported that no steps would be taken in regards to actual construction until after the end of the war.

The 1921 report of the Riley Memorial Association Secretary corroborates newspaper reports on the founding of the Association and its first steps:

The James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association is the outgrowth of several meetings held by Mr. Riley’s friends shortly after his death in 1916, at which time his friends held several meetings for the purpose of forming an organization to perpetuate Mr. Riley’s memory and establish some one or more suitable memorials. The world war necessarily caused a postponement of further efforts to carry out these projects…

The report continues to explain that the group gathered after the war and held their first meeting December 1, 1920. On May 24, 1921 the Association adopted Articles of Incorporation and Bylaws (filed April 9, 1921) and elected officers. The stated goals of the Articles of Incorporation were to “honor, extol and perpetuate the memory of James Whitcomb Riley” and to raise funds and acquire property in order to carry out several projects. These project goals included creating a children’s hospital, a children’s convalescent home, an endowment fund, and a “suitable shrine” to Riley’s memory.

[8] “Association Changes Its Name to Riley Children’s Foundation,” Indianapolis Star, April 2, 2003, 22, accessed Newspapers.com; “New Name, Same Commitment to Children,” Indianapolis Star, April 20, 2003, 24, accessed Newspapers.com.

On April 2, 2003, the Indianapolis Star reported, “The Riley Memorial Association last week said it has a new name—Riley Children’s Foundation.” The Foundation’s current mission can be found on their website here.

[9]“Big Hospital Memorial to Riley,” (Greenfield) Hancock Democrat, August 23, 1917, 8, accessed Newspapers.com; “Plan Children’s Hospital; To Be Riley Memorial,” South Bend News-Times, January 30, 1921, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Submit Plans for Memorial to Noted Poet,” (Lafayette) Journal and Courier, February 3, 1921, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Riley Hospital for Children Is Proposed,” Richmond Daily Palladium, February 9, 1921, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Memorial Articles Filed at Indianapolis,” (Muncie) Star Press, April 11, 1921, 5, accessed Newspapers.com; “Riley Month to be Observed by Hoosier State,” September 20, 1921, 8, accessed Newspapers.com; “Local Schools to Honor James Whitcomb Riley,” Richmond Daily Palladium, September 23, 1921, 8, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Pay Tribute to Memory of James Whitcomb Riley,” Greencastle Herald, October 7, 1921, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Furnish Hospital Room,” Richmond Daily Palladium, October 15, 1921, 4, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Rotary Club Committee Proposes to Spend $1,700 to Aid Blind, Crippled Children,” Richmond Daily Palladium, November 16, 1921, 8, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Advertisement, Jasper Weekly Courier, December 23, 1921, 8, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles ; “Help for Children Asked at Christmas” and “Riley Hospital Is Xmas Appeal,” Greencastle Herald, January 10, 1922, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Hospital Would Care for Indiana’s Crippled and Ailing Children,” (Munster) Times, April 13, 1922, 13, accessed Newspapers.com; “James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Hospital Would Care for Indiana’s Crippled and Ailing Children and Honor Famous Hoosier Poet,” Richmond Palladium, April 13, 1922, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Hospital Would Care for Indiana’s Crippled and Ailing Children,” Muncie Evening Press, April 13, 1922, 5, accessed Newspapers.com; “Drawings of Riley Memorial Hospital for Children,” Indianapolis News, April 13, 1922, 10, accessed Newspapers.com; “Front of James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children,” Indianapolis Star, April 14, 1922; 3, accessed Newspapers.com; Report of F.E. Schortemeier, Secretary, James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association, for the Year Ending December 31, 1921, James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association Minutes vol. 1, 1920-1926, transcription copy in IHB marker file.

While the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association began fundraising for a permanent tribute to Riley’s legacy began shortly after his death in 1916, and the idea of a children’s hospital was proposed as early as 1917, the project was delayed until after the end of World War I. See footnote 10 for information on the work done before the end of the war.

On December 31, 1921, the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association Secretary reported:

By far the most important work of the Riley Memorial Association during the past year has been the promotion of the James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children. Immediately upon the formation of the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association, the Association committed itself to undertake to establish the Children’s Hospital as its first objective. Upon investigation it was found that two other organizations, Indiana University and the Indiana Child Welfare Association, were interested in establishing a Children’s Hospital.

The report continued to explain that the three organizations met and consulted with Governor Warren McCray who offered his support. Representative Chester A. Davis of Jay County introduced a bill to the Indiana General Assembly. The bill passed both houses and appropriated $125,000 for the building with an annual appropriation of $50,000 for operating expenses. The report specified, “Ultimate control and management of the Hospital was places in the Board of Trustees of Indiana University and the law expressly recited that the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association shall submit advice, suggestions and assistance for the establishment and operation of the Hospital.”

Considerable numbers of newspaper articles corroborate the Association’s report. An extensive article in the Hancock Democrat on August 23, 1917, named the many businessmen involved in the early planning and shows that even at that early date they were planning to work with the state and Indiana University. Articles in Indiana newspapers show that Governor McCray submitted the bill to the Indiana General Assembly in February and that the legislature passed the bill in April of 1921. According to an article in the (Muncie) Star Press, in April 1921, the General Assembly “made provision for the state appropriation for the memorial hospital” and would be “under the direction of the board of trustees of Indiana University.” On September 20, 1921, the Muncie Evening Star Press reported on the fundraising efforts undertaken by the Riley Association and the Indiana Children’s Welfare Association “as well as numerous other civil and social organizations.” Indiana newspapers covered fundraising efforts over the following months and ran ads featuring forms for citizens to fill out and return with donations such as the one viewable here. Articles also show that individual Hoosiers, charitable groups, women’s clubs, rotary clubs, and school children also helped to raise funds for the hospital, according to many articles published in Indiana newspapers throughout 1921. Several newspapers ran extensive articles on April 13, 1922 giving the history of the hospital to date and publishing building plans.

[10] “Riley Memorial Is Sure,” Indianapolis Star, April 18, 1920, Indiana State Library, microfilm; “Rare Unpublished Views of Interior of Lockerbie Street Home of John R. Nickum Where James Whitcomb Riley Lived and Died,” Indianapolis Star, February 26, 1922, 12, 24, ISL microfilm; “Preserve Riley Home as Shrine,” Hammond Times, March 20, 1922, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Preserve Riley Home as Shrine,” South Bend News-Times, March 19, 1922, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Riley’s Old Home,” Richmond Palladium and Sun Telegram, March 21, 1922, 6, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; L.V. Schneider, “Hospital, Made Possible by Gifts, Fitting Memorial to Riley, Lover of All Children,” Richmond Daily Palladium, February 6, 1923, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

In April 1920, William Fortune, president of the Indianapolis Telephone Company purchased the property “so as to make sure that the home of the poet would be preserved as a memorial.” According to a February 1922 Indianapolis Star article, the Lockerbie home had remained unchanged in the years since Riley’s death and that visitors could see his “favorite spot” in the living room and his bedroom just as he left it. The article suggests that people were already visiting as if it were a museum, although it was not yet formally declared one. The same article reported, “It has been proposed that the land on either side of the old house be bought and made into a park for children – this with the house in the center to be kept as a memorial to Riley, so that Lockerbie street may always remain as closely connected with his memory as it was with his life.”

On March 20, 1922 the James Whitcomb Riley Association announced that it had purchased the Lockerbie home to “be preserved as a perpetual shrine for those who would pay it homage,” according to reports in several Indiana newspapers. According to the Richmond Daily Palladium, the Association opened the home to the public in April 1922.

[11] William Herschell, “Riley Hospital Is Birthday Tribute,” Indianapolis News, October 7, 1924, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Dr. Jessup on ‘Our Obligation to Childhood,’” Indianapolis News, October 7, 1924, 22, accessed Newspapers.com; “To Be Like Others Is Hope of Crippled Boy,” Indianapolis News, November 19, 1924, 21, accessed Newspapers.com; Annual Report of the Secretary Riley Memorial Association, January 14, 1925, James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association Minutes, 1920-1926, copy of transcription in marker file.

In his annual report, the secretary of the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association noted:

Nineteen-twenty four has been a year of achievement for the Riley Memorial Association for it has been a year of realization. The high point of the year was the opening of the James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children on November 19, when Mark Noble, an eleven year old child of Adams County was carried through the doors of the hospital.

The report continued, “Prior to the actual opening of the hospital the formal dedication ceremony took place. The date was October 7, the birthday anniversary of the Hoosier poet James Whitcomb Riley.”

Newspaper articles confirm the secretary’s report. On October 7, 1924 the Indianapolis News dedicated several pages to coverage of the hospital dedication. The News reported:

The dedication of the James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children held heart-interest for all Indiana. Men and women of notable standing in the city, state and nation gathered to pay tribute to the memory of James Whitcomb Riley, the Hoosier poet, and to open the doors of his memorial hospital as Riley would have opened them, to the little suffers of his state.

The Indianapolis Star continued the extensive on October 8 with extensive use of photographs of the previous day’s ceremony. On November 19, 1924, the Indianapolis News reported that the hospital received its first patient.

[12] “New Cabin Will Be Built at Camp Riley,” Franklin Evening Star, August 21, 1954, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Crippled Children Get $5,000 for Cabin at Camp,” Indianapolis News, August 23, 1954, 17, accessed Newspapers.com; “Two Weeks Camping for Handicapped Children,” Brookville Democrat, March 31, 1955, 8, accessed Newspapers.com; “Young Diabetics to Attend Camp,” Indianapolis News, April 25, 1955, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

Camp Riley was already under construction when multiple newspapers reported that the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association announced the construction of a new large cabin. The articles reported: “The camp is in Bradford woods, a 2,000 acre trace of woodhills nine miles south of Mooresville. It is being developed by the Association and Indiana University as a year round camping site for physically handicapped children.”

In March 1955, the Brookville Democrat reported that the Association was planning “a two-weeks camping session for physically handicapped children” at the camp. According to the same article, “The session is planned as a part of the first season use of Camp Riley, a winterized camp built under the joint direction of Indiana University and the Riley Memorial [Association] in the Bradford area.”

However, the camp was functional by that same spring. Camp sessions were already booked for the children of the University School in Bloomington for May 8-14, a Methodist children’s group May 28-June 4, and the Indianapolis Diabetic Association leased the camp from June 25-July 23, 1955.

Keywords

Arts and Culture; Buildings & Architecture