Location: 150 Courthouse Square, Greensburg (Decatur County, Indiana)

Installed: 2007 Indiana Historical Bureau, Division of Historic Preservation & Archaeology, IDNR, and Decatur County Freedom Trails Association

ID# : 16.2007.1

Text

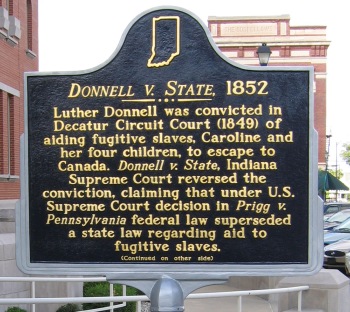

Side one:

Luther Donnell was convicted in Decatur Circuit Court (1849) of aiding fugitive slaves, Caroline and her four children, to escape to Canada. In Donnell v. State, Indiana Supreme Court reversed the conviction, claiming that under U.S. Supreme Court decision in Prigg v. Pennsylvania federal law superseded a state law regarding aid to fugitive slaves.

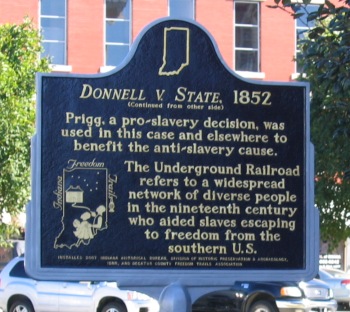

Side two:

Prigg, a pro-slavery decision, was used in this case and elsewhere to benefit the anti-slavery cause. The Underground Railroad refers to a widespread network of diverse people in the nineteenth century who aided slaves escaping to freedom from the southern U.S.

Keywords

African American, Underground Railroad

Annotated Text

Side one:

Luther Donnell was convicted in Decatur Circuit Court (1849) of aiding fugitive slaves, Caroline and her four children, (2) to escape to Canada. (3) In Donnell v. State, Indiana Supreme Court reversed the conviction, claiming that under U.S. Supreme Court decision in Prigg v. Pennsylvania federal law superseded a state law regarding aid to fugitive slaves. (4)

Side two:

Prigg, a pro-slavery decision, was used in this case and elsewhere to benefit the anti-slavery cause. (5) The Underground Railroad refers to a widespread network of diverse people in the nineteenth century who aided slaves escaping to freedom from the southern U.S.

Notes:

(1) The full name of this case heard by the Indiana Supreme Court was Luther A. Donnell vs. The State of Indiana. State of Indiana v. Luther A. Donnell, [3 Indiana 480 (1852)], Indiana Supreme Court, Appeals Decided, November Term 1852, Indiana State Archives, photocopy, p. [30]. (B00291)

(2) On March 23, 1848, Luther A. Donnell was indicted at the county courthouse in Greensburg by the Grand Jury of Decatur County Circuit Court. The first courthouse built on the public square in Greensburg was completed in 1827 and was the site of the Donnell indictment and trial. The present Decatur County courthouse was built on the same site in 1854. Lewis A. Harding, History of Decatur County Indiana (Indianapolis, 1915), 77-80 (B00727); Decatur County Interim Report (DHPA, DNR, 1999), 48, 50. (B00706)

The indictment stated that on November 3, 1847, Donnell, "with force and arms. . . did. . . knowingly harbor and conceal. . . slave Caroline. . . . [and] did. . . knowingly aid, assist and encourage to desert, escape, and flee from. . .George Ray [of Kentucky]. . . said slave Caroline. . . . " On October 2, 1848, Donnell's legal council asked the Decatur Circuit Court, to quash (set aside) both counts of the indictment arguing that: 1. the statute on which it was based was "inoperative, null and void" [based on Prigg v. Pennsylvania]; 2. the first count (harbor and conceal) was "uncertain and insufficient in law" for the state to maintain action against the defendant. The Court took this motion under advisement until the Spring Term, 1849. State v. Donnell, [1-5]. (B00291)

The Indiana law under which Donnell was indicted stated that any person convicted of assisting a slave to escape or hindering any person in lawfully recovering any "fugitive slave or person owing service, " could be fined up to $500. Laws of Indiana, 1843, p. 984. (B00691)

On March 27, 1849, Luther A. Donnell was arraigned and pleaded not guilty. State v. Donnell, [6-7]. (B00291) John S. Scobey and Andrew Davison served as attorneys for the prosecution while John Ryman and Joseph Robinson represented Donnell. The testimony and evidence submitted in this trial is included on pages [9-27] of State v. Donnell. (B00291) An advertisement for reward distributed by George Ray, Caroline's owner, of Trimble County, Kentucky provided a description of Caroline and her 4 children. State v. Donnell, pp. [11-12]. (B00291) On March 29, 1849, the jury returned a verdict of guilty on the second count of the indictment, assisting the escape of a slave. The court fined Donnell $50 to be paid for the Decatur County public seminaries. State v. Donnell, [7-8]. (B00291) On March 30, 1849, Donnell asked the court to set aside the verdict and grant a new trial based on the same arguments Donnell's legal counsel used on October 2, 1848. The court overruled these motions. Judges George Dunn and Samuel Ellis signed the judgment. State v. Donnell, [1, 8, 27]. (B00291) NOTE: The evidence presented in the trial was printed in full on the front page of the April 7, 1849 Decatur Clarion. "The Fugitive Slave Case, " Decatur Clarion, April 7, 1849, transcript and photocopy provided by applicant. (B00300)

(3) According to William M. Hamilton (a participant in the events who was named with Donnell in the civil suit by George Ray [Free Territory Sentinel, October 17, 1849]), Caroline and her children reached Canada safely; and in later years, she wrote Luther Donnell thanking him for his help. The "Personal Recollections of a ‘Rescue' case" by William Hamilton was printed for the first time in 1882. Atlas of Decatur Co. Indiana (Chicago, 1882), pp. 14-15, Indiana County History microfilm, Reel 6, no. 24, Indiana State Library. (B00299)

(4) On June 6, 1849, Donnell filed an appeal to reverse his conviction with the Clerk of the Indiana Supreme Court, H. P. Coburn. State v. Donnell, pp. [2-3, 7, 28-30]. (B00291) On November 24, 1852, the Indiana Supreme Court reversed his conviction, stating that the section of the Indiana statute on which Donnell was indicted (Laws of Indiana, 1843, Chapter 53, Section 115) was unconstitutional based on a U.S. Supreme Court decision, Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 16 Peters U.S. 539 (1842). The Indiana Supreme Court case is reported in Albert G. Porter, Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Judicature of the State of Indiana, 5 vols. (Indianapolis, 1853), 3:480-81. (B00070)

As Randall Shepard notes, this ruling "freed a Hoosier who had assisted a slave in escaping from Kentucky." Randall T. Shepard, "Slave Cases and the Indiana Supreme Court, " Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History, 15, no. 3 (Summer 2003): 37-38. (B00690)

In 1842, the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Prigg v. Pennsylvania stated that federal fugitive slave laws superseded state fugitive slave laws. Sandra Boyd Williams, "The Indiana Supreme Court and the Struggle Against Slavery, " Indiana Law Review, 30 (1997): 310. (B00295)

The 1787 U.S. Constitution addressed the relationship between Federal authority and "fugitives from labour, " establishing the right of slave owners to cross state lines to retrieve fugitive slaves. Article IV, Section 2 states: "No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Law thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due." U.S. Constitution, Art. IV, Sec. 5, http://Findlaw.com (accessed December 1, 2005). (B00689)

The federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 provided direction for the legal return of "fugitives" to their owners stating, "A person escaping from labour may be returned to the person to whom labour is owed by that person or his agent presenting oral testimony or written affidavit before a magistrate. Upon sufficient proof, a magistrate will issue certificate that will be warrant for removing fugitive to state from which he fled." "Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, " Race, Racism and the Law, http://academic.udayton.edu/ race/02rights/slave02.htm (accessed December 7, 2005). (B00694)

The Prigg decision was the first interpretation of the fugitive slave clause of the U.S. Constitution by the U.S. Supreme Court. The court ruled that slavery was protected by the U.S. Constitution; that the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was constitutional; that state laws interfering with the return of fugitive slaves were unconstitutional (null and void); and that slave owners or their agents could return alleged fugitives to slavery without any oral testimony or written affidavit, thus exposing any African American to kidnapping without legal recourse. The court decision also gave states the right to refuse to enforce the federal fugitive slave law. Interpretations of the decision provided other widely used avenues for anti-slavery and pro-slavery advocates. Paul Finkelman, "Prigg v. Pennsylvania and Northern State Courts: Anti-Slavery Use of a Pro-Slavery Decision, " Civil War History, 25, no. 1 (March 1979): 5-6, 8-10, 13-15, 21, 25-27. (B00702)

Indiana laws regarding fugitive slaves at first were concerned with the prevention of "manstealing, " the kidnapping of free African-American residents. As the issue of recapture of fugitive slaves became more heated, the Indiana General Assembly attempted to placate Kentucky slave owners while, in theory at least, continuing to provide a jury trial for alleged fugitive slaves. However, after the Prigg decision, the 1843 Indiana law concerning "any one owing service in any state or territory within the United States" provided no protection for an alleged fugitive or a free African-American resident. In 1846, a committee of the Indiana House of Representatives reported that based on the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Prigg v. Pennsylvania, federal laws probably superseded even the 1843 Indiana law on fugitive slaves. Emma Lou Thornbrough, "Indiana and Fugitive Slave Legislation, " Indiana Magazine of History, 50, no. 3 (September 1954): 214-19. (B00701)

State courts in Pennsylvania and Illinois cited the Prigg decision as the reason that civil claims for the value of slaves were heard in federal courts rather than state courts. Finkelman, Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 34. (B00702) In a civil trial in U.S. District Court in Indianapolis in 1849, George Ray sued Luther Donnell and William Hamilton for the value of Caroline and her children. The court ordered Donnell to pay Ray for the value of the escaped slaves, $1500; plus court costs, $1000; with lawyer's fees, approximately $3000. He was also liable to pay a $500 action of debt penalty to the plaintiff. In a statement to the Centerville (Indiana) Free Territory Sentinel, Donnell commented that paying these fines and charges would represent a financial burden, and he asked readers for subscriptions of small sums to offset his expenses. Donnell collected at least $800.00 locally. Among those individuals Donnell authorized to procure "subscriptions" were noted anti-slavery advocates and abolitionists, George Julian, James H. Cravens, John Rankin (Ohio), Laura Haviland (Michigan) and several others. Justice John McLean, Western Law Journal, 1, no. 12 (September 1849), ProQuest, American Periodicals Series Online, 1740-1900 (accessed February 7, 2006, through Indiana University-Bloomington Web site). (B00726) Centerville (Indiana) Free Territory Sentinel, October 17, 1849. (B00703) NOTE: The 1850 Census listed the value of Luther Donnell's real estate at $10, 000. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Schedule 1, 1850, Fugit Township, Decatur County, Indiana. (B00708)

5) After the Court rendered the Prigg decision, anti-slavery advocates hailed it as a victory for the "slave powers." The decision extended the laws of the slave states into the non-slave states. However, the decision became a useful tool for anti-slavery advocates. According to Finkelman, the growing anti-slavery use of Prigg was one of the factors leading to the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Finkelman, Prigg v. Pennsylvania, [5], 13, 16, 20-22, 31. (B00702) Anti-slavery lawyers and judges used Prigg for opposing the return of fugitives to slavery. In three Indiana cases the courts hindered slave owners from outside Indiana in taking escaped slaves back to slave states. See Norris v. Newton (1850) [18 F.C. 322]; State v. Graves (1849) [1 Indiana 368]; and Vaughan v. Williams (1845) [28 F.C. 1115]. Finkelman, Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 22. (B00702) In Freeman v. Robinson (1855) [7 Indiana 321], a free black man, using Prigg, won a suit against a federal marshal for false arrest and assault. In a pro-slavery decision, Graves v. State, (1849) [1 Indiana 368], the Indiana Supreme Court cited Prigg to reverse the conviction of three Kentucky slave catchers for inciting a riot. Finkelman, Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 29-30, 33. (B00702)

The Indiana Supreme Court often aligned itself with anti-slavery interests in Indiana. Shepard, 35. (B00690) In Lasselle v. State, 1 Indiana 60 (1820), the Indiana Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, freed an African-American woman in Vincennes from slavery, stating that the 1816 Indiana Constitution prohibited slavery in Indiana. The Indiana Supreme Court in deciding In re Clark, 1 Indiana 122 (1821), held that legally indentured servitude was essentially the same as slavery, and thus, prohibited by the Indiana Constitution. Justices James Scott, Jesse Holman, and Isaac Blackford heard both cases. Shepard, 36. (B00690) The Indiana Supreme Court's anti-slavery inclinations continued through 1852. According to William Wesley Woollen, Justice Blackford "hated slavery, and during his whole life his influence was against it." William Wesley Woollen, Biographical and Historical Sketches of Early Indiana (Indianapolis, 1883), 350. (B00709) See Suzann Weber Lupton, "Isaac Blackford: First Man of the Court, " Indiana Law Review, 30 (1997 ): 322, n. 28. (B00700).