Indiana's governmental roots can be traced back to the territorial era, when simple buildings served as the capitols. In 1813 the assembly for the Indiana Territory petitioned the U.S. Congress to move its capital from Vincennes to Corydon. Corydon then became the state capital when Congress made Indiana a state in 1816. Corydon's Statehouse was a two-story building originally constructed to be the Harrison County Courthouse. Its floor was made of flagstones and covered with sawdust. A small tower topped the building, and large fireplaces heated both floors.

The seat of state government officially moved to Indianapolis in 1825, just four years after Alexander Ralston laid out the town. Weeks before, State Treasurer Samuel Merrill had transported state documents and the treasury to the new capital in wagons. That trip, which takes about three hours on modern highways, took Merrill ten days to complete over the rough roads and trails between Corydon and Indianapolis.

The legislature at first rented quarters in the Marion County Courthouse, but by 1831 the General Assembly had authorized construction of a state capitol building. It was funded by the sale of lots within the ten-year-old town, which counted approximately 1,900 residents by then.

Commissioner James Blake offered a $150 award for the best plan for the Capitol. The design of New York architects Town and Davis was chosen from the twenty-one entries submitted. Like most of the drawings offered, the design of Town and Davis featured a Greek Revival style. This architectural style had become common in public buildings of the period because a recent political revolution in Greece had reawakened the interest of Americans in their own democratic roots.

The contract between Town and Davis and the General Assembly called for a building that would "correspond in character...with the Parthenon" in Athens. The well-known architects added a dome to their design, which proved to be a somewhat controversial element. It drew praise from some, but criticism from others, including architectural purists who pointed out that the Greeks did not have domed buildings and a disgruntled Hoosier who called it a "Greek temple with a cheese box on top."

Initially, however, many Hoosiers were pleased with their Capitol, which was completed ahead of schedule. One local newspaper deemed it "truly splendid." And so it must have seemed to many whose town streets were "knee-deep with mud" when it rained, a problem made doubly troublesome by the fact that Indianapolis did not yet have sidewalks.

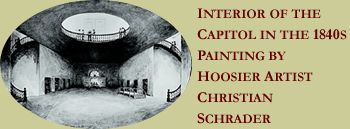

The completed Capitol must have shone in that environment. It rose two stories from a foundation of blue limestone, and its brick exterior walls were stuccoed to resemble granite. A zinc roof topped the building and the dome. The interior plan called for offices of the governor and other state officials to be on the first floor. Halls for each of the legislative houses were located on the second floor.

The General Assembly charged the state librarian, Nathaniel Bolton, with the care of the Capitol. In addition to his duties of tending to the library, he maintained the fence and gates, trimmed the trees on the property, and mowed the lawn. His wife, Sarah, a poet and advocate of woman's rights, sewed carpets for the building.

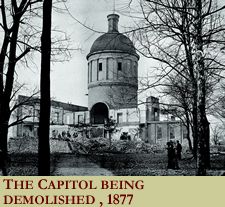

Over the next few decades, while the state progressed, the Capitol lost most of its luster. By the end of the Civil War, Greek Revival architecture was out of favor, and the building was drawing increasing criticism for its design. Worse, it had begun to deteriorate. By the 1860s the soft blue limestone foundation was failing, and the stucco was chipping off, causing one local historian to call its appearance "disgusting." In 1867 the ceiling in the Representative Hall collapsed. After an 1873 Statehouse Committee in the General Assembly failed to find a solution to the structural problems, it was only a few years before the Capitol was condemned and demolished.  By 1877 Indiana had become one of the thirteen most populated states in the U.S., and the population of Indianapolis had grown to nearly 75,000. The capital city had earned the nickname "Crossroads of America" because so many rail lines met at Union Station, just a few blocks south of the Capitol.

By 1877 Indiana had become one of the thirteen most populated states in the U.S., and the population of Indianapolis had grown to nearly 75,000. The capital city had earned the nickname "Crossroads of America" because so many rail lines met at Union Station, just a few blocks south of the Capitol.

The legislature's decision to build a new capitol building was based on practical necessity, but it was also supported by a growing desire among Indiana citizens to be viewed as residents of a progressive, important state. Even before it was demolished, this capitol building had not conveyed that image.

Despite its relatively short life, the first Capitol in Indianapolis had been a silent witness to innumerable history-making events. Included among them were the near-bankruptcy of the state in 1839; legislative debates on woman's rights; the beginning of free, public education; and the end of the Whigs and birth of the Republican party. The building had seen the creation of a new State Constitution in 1851 that prohibited the settlement of African Americans in Indiana, and it had held in state the body of the Great Emancipator, Abraham Lincoln. (In 1866 Article 13 of the State Constitution forbidding settlement of African Americans was declared void by the Indiana Supreme Court.)

The Capitol had also provided a meeting space for Hoosiers. For example, in 1859 the members of Christ Church met in the building while their new church was under construction. The initial session of the Indiana Medical College was held there a decade later.

In 1877 the General Assembly created a commission to supervise the erection of a new capitol building, the present Statehouse. The old Capitol had served its purpose, but it would soon be replaced by a grander and sturdier structure.