Indiana's Statehouse saw many changes in its first hundred years. An ever changing cast of legislators, office workers, judges, and citizens walked its halls. Indianapolis grew up around the Statehouse, as nearby homes and commercial buildings were the Statehouse itself undergone updates and additions.

Indiana's Statehouse saw many changes in its first hundred years. An ever changing cast of legislators, office workers, judges, and citizens walked its halls. Indianapolis grew up around the Statehouse, as nearby homes and commercial buildings were the Statehouse itself undergone updates and additions.

Shortly after the Statehouse was built, Finnish Baroness Alexandra Gripenberg stopped in Indianapolis during an American tour and marveled at the building. She observed that "in its halls one can meet people of all kinds." She found "small boys with crackers in their hands, men who squirt tobacco juice on the stairs, schoolgirls, tourists, college students, and women dressed in silk." It was clearly a house for all who called themselves Hoosiers.

It was here that people came to remember Indiana's role in the Civil War, which ended in 1865, long before the Statehouse was built. In the years following that conflict, Indiana established itself as the "home of patriotism." For a while it even served as the national headquarters of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), an organization of Union veterans from the Civil War. In fact, the GAR met several times in Indianapolis.

Later a statue of Indiana's war governor, Oliver P. Morton, was added to the east entrance, along with two plaques honoring Morton's and Indiana's role in saving the Union. Rudolf Schwartz, the sculptor of the Morton statue, also carved the statuary on the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument in Indianapolis.

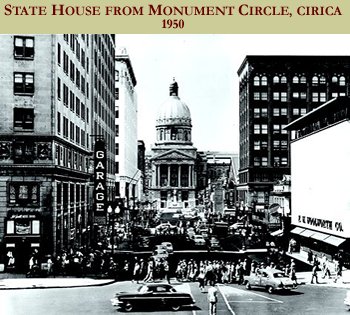

With the completion of the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument (1901), the Federal Courthouse (1905), and the public library (1917) along Meridian Street, a movement grew to replace the 1888 Statehouse. Some said that the building was already too small for the offices of state. Others wanted it moved to Meridian Street, where the parades that marked public life in the early twentieth century usually took place.

Still, in times of extreme distress, when people hoped to capture the attention of the governor or the General Assembly, parades and protests made the Statehouse their focus. For example, 8,000 citizens marched to the Statehouse lawn in 1913 to protest a work stoppage by streetcar drivers and the city's inability to control the violence that had erupted during the strike.

At other times commemorations of a different sort took place at the Statehouse. Just as the old Capitol briefly had held the body of Abraham Lincoln, who spent most of his boyhood in Indiana, Hoosiers came to the Statehouse to pay their final respect to public figures. These included Governor Alvin P. Hovey (1891), President Benjamin Harrison (1901), U.S. Senator and Vice President Charles Warren Fairbanks (1918), and the beloved Hoosier poet James Whitcomb Riley (1916). People also honored the sacrifice of private citizens here, including Evansville resident James Bethel Gresham, the first American soldier killed in World War I, whose body lay in the rotunda.

Little of the grand celebration that accompanied the state's centennial in 1916, however, took place at the Statehouse. In most cases these events were held at the state fairgrounds, at parks, or at the Circle. One exception was the ceremony at which the Daughters of the American Revolution presented a fountain and a marker memorializing the Old National Road (today known as U.S. 40 and Washington Street). At the unveiling ceremony, Governor Samuel Ralston praised the women's "high degree of civic virtue."

Little of the grand celebration that accompanied the state's centennial in 1916, however, took place at the Statehouse. In most cases these events were held at the state fairgrounds, at parks, or at the Circle. One exception was the ceremony at which the Daughters of the American Revolution presented a fountain and a marker memorializing the Old National Road (today known as U.S. 40 and Washington Street). At the unveiling ceremony, Governor Samuel Ralston praised the women's "high degree of civic virtue."

Across the United States, women with "civic virtue" had sought the right to vote since the 1850s. The Indiana General Assembly had allowed them to use its chambers for suffrage meetings as early as the 1870s, but few victories had been achieved. In 1911 the women of Indiana presented a bust of State Senator Robert Dale Owen to the Statehouse to honor his work on their behalf and to draw attention to their ongoing desire for the vote. (Many years later, the bust was stolen from the State House grounds.) Two years after the presentation of the Owen bust, suffragists marched on the Statehouse. It was 1920 before the General Assembly ratified the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, granting women the vote.

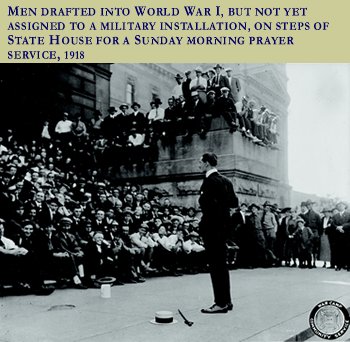

As the struggle for women's suffrage was making inroads, the United States entered the Great War, as World War I was called at the time. While Indiana women knitted socks and rolled bandages for soldiers, leaders worried about traitors and "subversives." From his office in the Statehouse, Governor James P. Goodrich established the "Liberty Guards" in 1917. Its mission was to maintain order and to watch for anyone who might be working against the war effort.

The crisis of the war finally quieted cries for a new State House, and renovation of the existing structure began. The increasing number of state employees and offices had led to the need for more room, so in 1917 workers converted some of the stable area in the basement to finished space.

Office space was at such a premium that in 1919 the collection of the State Museum, which had occupied a large room on the third floor of the Statehouse, moved to the basement. In the final stages of the renovation on the building (1917 to 1920), workers repainted walls in "brighter colors" and reworked the original gas and electric chandeliers.

A desire to reform society arose after the war. In addition to the 19th Amendment, in 1919 the Indiana General Assembly ratified the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited the manufacture, sale, and transportation of intoxicating liquors. Along with others across the country, Indiana's temperance workers believed that Prohibition would make the state safer and more wholesome.

By 1920, the U.S. Census deemed Indiana an urban state. More people now lived in cities than in rural areas, and for the first time fewer than half of all Hoosiers counted farming as their principal occupation. Automobiles became a common sight. Northwest of the Statehouse, jazz music resounded on Indiana Avenue. Flappers danced the night away.

The patriotic feelings born during the war continued into the 1920s. The recent Russian revolution and changes in society had evoked fear that Bolsheviks or anarchists were plotting an overthrow of the government. In a show of loyalty, Italian Americans presented a bust of Christopher Columbus to the state.

While cries of patriotism rang in the air, scandal tainted the state's highest office. Governor Warren T. McCray was convicted of mail fraud in 1924 and forced to resign. That same year, citizens elected an advocate of clean government, better schools, and lower taxes, Edward Jackson, as governor. Jackson, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, was indicted but not convicted of bribery in 1928.

The decade-long Great Depression saw few changes to the Statehouse. Early in the decade, in 1931, the building had its first exterior steam cleaning. Three years later, the Indiana State Library, the Indiana Historical Bureau, and the Indiana Historical Society moved to a new building across Senate Avenue. This freed up space for a growing state government.

The troubled times of the Great Depression spurred reform in state government. Governor Paul V. McNutt envisioned government as "a great instrument of progress." From his office in the Statehouse, he reorganized state government and strengthened the power of the governor. A similar feat had been attempted by Governor Thomas R. Marshall in 1911 with his so-called "Marshall Constitution," which the Indiana Supreme Court found unconstitutional in 1912.

With the General Assembly, McNutt was able to pass legislation providing funds for public relief and welfare as well as an income tax act. It has been said that no governor since the Civil War's Morton has had as much of an impact on state government as McNutt.

Henry F. Schricker, Indiana's only non-consecutive two-term elected governor, led the state during World War II, a time of rationing, blackouts, and fire drills. To coordinate civil defense, Schricker and the General Assembly established the Indiana State Council of Defense and worked with federal agencies to boost war production in Hoosier factories and to raise money for the war effort through bond drives.

During and after World War II, the General Assembly began to examine racial discrimination. Robert Lee Brokenburr, the first African American elected to the State Senate, helped draw attention to racial injustices. As a result, the General Assembly passed landmark legislation. This included a 1947 anti-lynching law and a 1949 act that gradually eliminated segregation in public schools-years before Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka, a 1954 landmark case in national history.

Indiana entered a period of prosperity with the war's end. Hoosiers, like the rest of the nation, rushed to purchase new cars, appliances, and homes. Historic architecture was not greatly appreciated in a society focused on the future.

As a result, the Statehouse experienced "modernization" in the late 1940s. Workers removed the original oak doors on the north and east sides of the building and replaced them with new glass entry doors. Considered dated, the 1919 wall sconces were replaced with the popular new fluorescent fixtures.

In the next few years, the architectural firms of Walter Scholer and Associates of Lafayette and Miller and Yeager of Terre Haute redesigned the House and Senate chambers to create additional office space. In the process workmen removed the original granite columns, wooden balconies, and ornamental plaster ceilings in the chambers and installed up-to-date electric voting boards. The renovations were not always popular. "Hoosier lawmakers walk on plush carpets [and] relax in deep seated armchairs ($84 each)," complained one local paper.

While newspapers criticized extravagance, they also drew attention to the fact that the Statehouse needed renovation. Over the next few years, the last of the stables in the basement were converted into office space, and workers painted the Supreme Court walls.

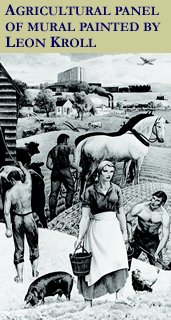

In 1952 came one of the more controversial changes to the Statehouse. New York artist Leon Kroll painted a mural for the Senate chamber in three panels depicting scenes of Indiana. In an era of strong anti-Communist feelings, one legislator charged that the artist belonged to twenty-two Communist organizations. Another thought that the "people in the farm picture look like Bolsheviks." The Legislative Advisory Committee refused to bow to the paranoia of the moment, and the mural remained in place until a 1970s remodeling.

In 1952 came one of the more controversial changes to the Statehouse. New York artist Leon Kroll painted a mural for the Senate chamber in three panels depicting scenes of Indiana. In an era of strong anti-Communist feelings, one legislator charged that the artist belonged to twenty-two Communist organizations. Another thought that the "people in the farm picture look like Bolsheviks." The Legislative Advisory Committee refused to bow to the paranoia of the moment, and the mural remained in place until a 1970s remodeling.

Beyond the problem with the Kroll mural, Hoosiers felt that their Statehouse looked faded and was not up to the standard of other state houses. "Indiana's Capitol Dome Mars Planned Skyline" ran a headline in one newspaper in 1958. Soot from area factories covered the dome, which was also "marred by rifle shots," perhaps some of which were the work of Judge James Emmert.

At times Emmert lived in his office at the Statehouse when the Supreme Court was in session rather than make the round-trip to his home in Shelbyville. One clerk recalled the judge sitting in a third-floor window in the late 1940s, practicing his marksmanship on the pigeons that flocked around the building. Another remembered seeing him shuffling along the corridors of the State House at night in his bathrobe.

It is hard to imagine such informality, especially as government grew in power and prestige in the 1960s. A new State Office Building opened, freeing up space in the State House. A pedestrian tunnel provided access to the new building from the Statehouse and the State Library building. In 1964 the Indiana State Museum finally moved out of its basement quarters into the former Indianapolis City Hall at Alabama and Ohio streets.

Although the late 1960s and the early 1970s were times of turmoil, with race riots and Vietnam War protests nationwide, only a few such activities took place in Indiana. This era did see a change in the way the General Assembly operated. Indiana's part-time legislature has always been composed of citizen legislators, who work at other jobs when the Assembly is not in session. Since the pioneer era, the Assembly had met every other year, but in 1971 it began meeting annually. The demands of government had become too great.

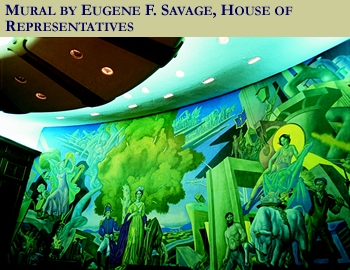

These were also years of rebuilding and change at the Statehouse. The Chapel, which had been dedicated by Governor Matthew Welsh in 1964, was moved to the building's fourth floor, in part to halt its use as a legislative meeting room. Workers again remodeled the House and Senate chambers, and Covington, Indiana, artist Eugene F. Savage painted a mural for the House of Representatives. Unlike the mural added to the Senate a decade earlier, this work of art evoked no controversy.

The bicentennial of the nation in 1976 increased feelings of patriotism and interest in history. By then, Indiana had seen many historic structures torn down, and citizens who mourned their passage began to work to save the buildings that remained. In 1975 the Indiana Department of Natural Resources nominated the State House for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. Three years later, workers reclad the capitol dome in copper. In 1984 the art glass inner dome suspended over the rotunda was cleaned and repaired. These relatively modest renovations set the stage for a major restoration to come.

The Indiana Statehouse saw many physical changes on its grounds and within its walls in its first hundred years. It provided a setting for discussions on such issues as the role of labor, civil rights, women's rights, and more. Through it all, the building itself stood as a changing but constant sentinel. By the 1980s its age was showing, but the Statehouse remained a sturdy, dynamic edifice. It would soon receive a facelift that would restore it to its earliest grandeur.