One hundred years after its completion, Indiana's Statehouse underwent a major renovation/restoration which was part of the statewide "Hoosier Celebration 88" announced by Governor Robert D. Orr at his inauguration. The restoration at the Statehouse was one of the most visible elements of this yearlong celebration, which in itself renewed interest in historic architecture in many communities across the state.

One hundred years after its completion, Indiana's Statehouse underwent a major renovation/restoration which was part of the statewide "Hoosier Celebration 88" announced by Governor Robert D. Orr at his inauguration. The restoration at the Statehouse was one of the most visible elements of this yearlong celebration, which in itself renewed interest in historic architecture in many communities across the state.

It was apparent that the Statehouse had suffered decades of "benign neglect." Dirt and destructive cleaning processes had marred the exterior. Layers of paint on the interior and renovation projects of limited scope had obscured much of the original elegance. Even the magnificent dome leaked. The hundredth anniversary of the building proved to be the perfect time for a facelift.

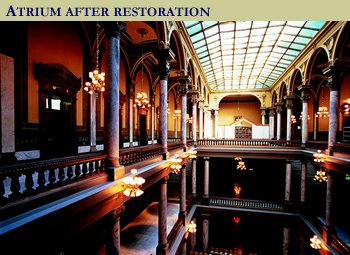

A thorough cleanup of the stonework was required both inside and out. Marble and granite columns, pilasters, and capitals in the interior were cleaned and polished to a rich luster. Details of the eight Carrara marble statues in the rotunda became visible for the first time in many years during this cleaning.

Woodwork was stripped and repaired, and the finish was restored. Glass entry doors were replaced with reproductions of the original oak doors. Modern-day artisans reproduced handcrafted door moldings and other decorative elements.

A Victorian aura returned to the rotunda and atriums. Three layers of paint-the last applied in 1958 by prison labor-hid original stenciling. Indianapolis artisans spent months on the painstaking restoration. In recreating the original details, one of the architects later noted that "more than four acres of plaster needed to be hand stenciled."

Lighting, too, drew upon the past. The fourth floor still had its original chandeliers; from these, new ones were recreated for the other floors. None of the original sconces remained in the building, but one was found in Indianapolis. The restorers replicated it and mounted the copies where the originals had once hung.

The massive art glass interior dome, a hallmark of the State House, received repairs. To ensure that light filtered evenly through the dome to the floor of the rotunda more than 100 feet below, workers painted the interior surface of the outer dome with highly reflective white epoxy paint and added artificial light behind the glass. As a result, the colors of the interior dome glow richly even on cloudy days.

The work on the Statehouse drew praise, especially for the architectural firm the Cooler Group. According to the juror of one award, "This is restoration at its best. It glows. The vitality of the materials has been brought back." Attention to detail allowed the restoration/renovation to recapture much of the original nineteenth-century ambience.

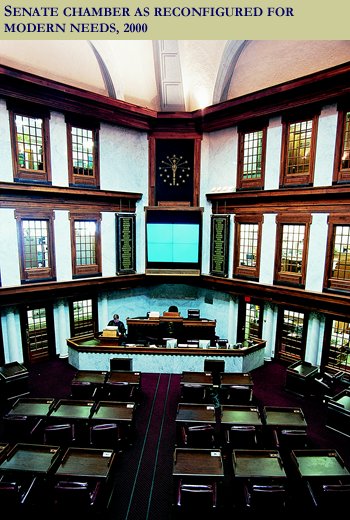

An equally important goal, however, was to make the building functional for the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Technological improvements, such as computerization of the lighting systems, were central to the plan. Modern informational and security systems were designed to harmonize with the building's historic character. Yet even in such an up-to-date environment, it is still one worker's full-time job to change light bulbs in the building.

An equally important goal, however, was to make the building functional for the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Technological improvements, such as computerization of the lighting systems, were central to the plan. Modern informational and security systems were designed to harmonize with the building's historic character. Yet even in such an up-to-date environment, it is still one worker's full-time job to change light bulbs in the building.

While many of the public areas were involved in the restoration, other areas remained virtually untouched. The governor's office is one such room.

Another is the Indiana Supreme Court courtroom, which still looks much as it did in the nineteenth century. It escaped the "modernization" that destroyed details in other parts of the building. When the carpet became worn in 1984, an exact copy was ordered to maintain the historic character of the courtroom.

The chambers of the General Assembly were not restored to their Victorian character. In order for Indiana's General Assembly to continue meeting in the State House, its offices and chambers had been remodeled in the 1960s and 1970s to meet the demands of a functioning legislature. Offices installed around the periphery of the chambers allowed for more efficient use of space. New seating and lighting were added to both the House and the Senate at that time to ensure that these rooms served the lawmakers' needs.

Indiana's Statehouse remains a place of civic activity. Though many supporting offices have moved off-site, all three branches of government continue to work here. In the 1990s, the State Government Center grew to include two new parking garages and a new five-story state office building. The Statehouse no longer contains all of the functions of government, as it did in 1888, but it serves as the working anchor for a 49.5-acre governmental campus.

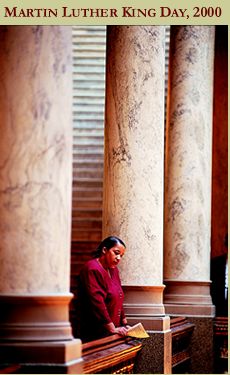

The revitalized Statehouse has proved to be an engaging public space for civic life. Our representatives take the oath of office in its chambers. Solemn words resonate through the building as Indiana State Police and Department of Natural Resources Conservation Officers are sworn in. Businesses receive Half-Century and Century Awards for longtime contributions to the state's commercial life, and farm families are recognized here with Hoosier Homestead Awards for their role in perpetuating Indiana's agricultural heritage.

The revitalized Statehouse has proved to be an engaging public space for civic life. Our representatives take the oath of office in its chambers. Solemn words resonate through the building as Indiana State Police and Department of Natural Resources Conservation Officers are sworn in. Businesses receive Half-Century and Century Awards for longtime contributions to the state's commercial life, and farm families are recognized here with Hoosier Homestead Awards for their role in perpetuating Indiana's agricultural heritage.

People gather at the Statehouse to express their views on a variety of subjects, from capital punishment to the environment to the economy. Indeed, a few members of the Ku Klux Klan brought an uncomfortable memory to the fore with State House demonstrations in the 1990s. And, reminiscent of an earlier era, thousands gathered for a labor rally in 1995 at the State House.

The Statehouse also provides an appealing site for other kinds of activities. Music from symphonies and choral groups swells through the rotunda and atriums during concerts. Children hang ornaments from branches of the state's holiday tree in the rotunda, and couples joyfully take their wedding vows here.

The Statehouse has yielded its share of mysteries. As in many old buildings, rumors of ghosts haunting its halls arise in October as Halloween nears. Treasures have been unearthed, including an old brass cannon and models of monuments found in the basement in 1905, and the seven bars of silver found locked in an old safe in 1995. Discoveries such as these contribute to the lore of the State House.

With all of the activities occurring here, it is easy to see that this is a site where both the past and the present unfold. This is a twenty-first-century working office building with the history and restored grandeur of a nineteenth-century public space.