Patient Life at Central State During the Nineteenth Century

A Sick Society: The Causes and Treatment of Insanity in the Nineteenth Century

Changing Their Focus: Central State Hospital's Medical Staff and the Emergence of Scientific Medicine

- Introduction

- Specialists Join the CSH Medical Staff

- Sarah Stockton, M.D.(1842-1924)

- The New Pathology Department and Scientific Research

Many thanks to the Indiana State Library and Indiana Medical History Museum for sharing resources for this exhibit.

Introduction

Aerial Photograph of Central State Hospital, 1920s [40 kb]

Aerial Photograph of Central State Hospital, 1920s [40 kb]

While the Indiana legislature had authorized the establishment of a "hospital for the insane" as early as 1827, the doors of the Indiana Hospital for the Insane (later re-named Central State Hospital) did not open until 1848. At that time, the hospital consisted of one brick building situated on a large parcel of land, numbering over a hundred acres, in the outskirts of Indianapolis. From 1848-1948, the hospital grew yearly until it encompassed two massive, ornate buildings for the female and male patients, a "sick" hospital for the treatment of physical ailments, a farm colony where patients engaged in "occupational therapy", a chapel, an amusement hall complete with an auditorium, billiards, and bowling alleys, a bakery, a fire house, and a cannery.

Central District, 1899 [105 kb]

Central District, 1899 [105 kb]

For a half-century, this complex array of buildings and gardens beckoned to all of the state's mentally ill. By 1905, however, mental health institutions built in Evansville, Logansport, Madison, and Richmond relieved an overcrowded Central State Hospital of some of its patient load, leaving it to treat only those from the "central district", an area of 38 counties situated in the middle portion of the state.

Central State Hospital Aerial Photograph, 1985 [71 kb]

Central State Hospital Aerial Photograph, 1985 [71 kb]

By the late 1970s, most of the hospital's ostentatious, Victorian-era buildings were declared unsound and razed. In their place, the state constructed brick buildings of a nondescript, institutional genre. These modern buildings and the medical staff therein continued to serve the state's mentally ill, until allegations of patient abuse and funding troubles sparked an effort to forge new alternatives to institutionalization which, in turn, led to the hospital's closure in 1994. Fortunately, the Indiana State Archives, the Indiana State Library, and the Indiana History of Medicine Museum (housed in one of the hospital's remaining nineteenth-century edifices), are preserving the history of an institution that served, albeit not always well, the mentally ill of Indiana for 146 years.

Back to the Central State Hospital Index

Collection Description

Access: Due to HIPPA regulations and Indiana State Law, all mental health records are considered confidential. If a patient is still living he or she may sign a release granting permission for copies of the records. Family members may request information from a deceased patient's records only after establishing a clearly documented relationship. Please e-mail the State Archives for further information.

Note: When sending an email to the Indiana State Archives, please be sure to include a very clear subject heading, i.e, Civil War, Soldier's Home, Hospital Records, Morton Telegrams, etc. Emails without a clear subject heading may be mistaken as spam or a potential virus and be filtered out automatically. If you have not received an initial response from the Indiana State Archives within a few weeks, please resubmit your request.

- Central State Hospital Annual Reports, 1845-1994

Includes: patient care procedures, patient statistics, causes and treatments of mental illness, physical plant improvements, budgets and financial transactions; post-1880 reports include medical research records.

- Admission Books, 1858-1924

Includes: patient histories, causes of mental illness, diagnoses, treatments, county of residence, education level, religion, birthplace, by whom committed and supported, effectiveness of treatment, when admitted and discharged.

- Commitment Papers, 1848-1950

Records from the county circuit courts giving legal authorization for committal, including statements of insanity from relatives or friends; physicians' diagnoses; extensive information on patient's health, physical appearance, and drug use; patients' personal histories; and certificates of the justice of peace.

- Community Volunteer Program, 1960-1994

- Correspondence, 1870-1994

Includes: acceptance and discharge letters from CSH medical superintendent to patients, county courts, and patients' guardians, 1848-1900; correspondence exchanged between CSH medical superintendents' and county courts; physicians' correspondence to patients and Legislative Visiting Committee, 1890-1937; bulk of 20th-century correspondence dates from 1950-1994 and includes departmental and administrative correspondence.

- County Books and Petty Registers, 1855-1924

Includes: patient admission and discharge dates, organized by county and township.

- Discharge, Subpoena, and Clothing Requisition Papers for CSH Patients, 1848-1900

Discharge Papers: date of discharge, county discharged, under whose care.

Subpoena Papers: addressed to relative or friend summoned to testify that the individual in question was indeed insane.

Clothing Requisitions: level of personal hygiene, clothing patient arrived in, and clothing needed.

- Records of Disturbed Patients, 1945-1952

Daily reports detailing patients' complaints and disruptive behavior.

- Financial and Statistical Reports, 1945-1994

- Legal Files, 1960-1994

- Legislative Visiting Committee's Reports on Central State Hospital, 1890-1912

Includes: investigations of misconduct and patient abuse.

- Night Watch Books, 1912-1916

Women's Medical Ward (Sick Hospital): 1914-1915

Men's Medical Ward (Sick Hospital): 1912-1914: Includes: physicians' instructions detailing drug treatments to be administered by overnight medical attendants; attendants' morning reports to physicians.

- Patient Master Card File, 1848-1970s

Includes: patient diagnosis, admittance and discharge dates, marital condition, occupation.

- Patient Medical Charts (Microfiche), 1930-1970s

- Photographs and Illustrations, 1900-1990

Small photo collection, primarily of the medical staff and hospital buildings from the early 1900s and 1960-1990. The Archives and the State Library have several lithographs of the original hospital structures. A much larger collection of Central State Hospital photographs, including patient photographs, are housed at the Indiana Medical Museum, Indianapolis, Indiana

- Policies, Minutes, Programs, and Manuals, 1940-1994

- Prescription Books, 1858-1864

Includes: patient histories, diagnoses, treatments, including drug prescriptions.

- Psychiatric Nursing Program for Collegiate Schools of Nursing, 1953-1958

Includes: correspondence, course outlines, student handbooks, CSH nursing program for Depauw students, surveys.

- Research Reports, 1960-1994

- Transfer and Recovery Books, 1906-1919

Books document transfers to Central State's "Sick" hospital for treatment of physical ailments; includes date of transfer and removal, and description of ailment and treatment.

Back to the Central State Hospital Index.

Life at Central State

Amusement

Patients were treated to an occasional outing or in-house performance. Dramatic and musical clubs performed plays and musical numbers in the hospital auditorium. Sojourns to the fair, baseball games, and the circus were offered once or twice a year.

Fourth of July Picnic for CSH Patients, circa 1920; first Fourth of July picnic held in 1889 (576 KB)

In warmer weather, the hospital held Fourth of July picnics and dancing parties for patients in the outdoor pavilion. CSH celebrated Christmas by hosting a holiday celebration, during which the staff presented a gift to each patient. The hospital also held religious services on the Sabbath for Christian patients.

Hospital Grounds, circa 1893 (120 KB)

In 1879, the hospital built a ten pin bowling alley and a room for pool and billiards tables; the patients and the staff were thrilled. Patients also spent much of their free time strolling about the hospital's idyllic grounds and greenhouse.

Work

Physically able patients spent most of their days working. Early in the century, work was more recreational -- merely a means of occupying the time of bored patients. As the century progressed, however, work became more regimented and production oriented. Clearly, the new industrialism of Victorian period had influenced "work therapy" at Central State Hospital (CSH).

During the early years of CSH, women's work was confined to sewing, knotting, and knitting. Later in the century, the influence of industrialization became apparent in women's work at the hospital. The introduction of garment piece work in the nineteenth century and sewing machines in the early twentieth indicated that industrialization had crept into the minds of CSH physicians and into the work rooms of the hospital.

A similar pattern emerged in men's work at the hospital. Early in the century, able male patients worked on the hospital farm or manicured the hospital's lawns and gardens. Later, other forms of hard labor were introduced such as excavating land for the hospital's new boilerhouse and digging trenches for steam pipes. Early in the twentieth century, CSH built a canning factory for patients and purchased new machinery for the men's work room. The hallmarks of nineteenth-century industrialization, such as factories, and steam and electric power, had transformed patients' work.

Work, most likely, was an effective therapy for mentally-ill people in this period. Yet, it also served important political and social functions: politicians and the voting public alike wanted reassurance that patients who left CSH would become productive Hoosiers, rather than dependents of the state. Requiring patients to work while they received treatment at CSH was one way to encourage patients to work after their discharge.

Education

In 1885, CSH opened a school on the women's wards. The school reflected a growing reform movement that sought to introduce public education to the masses. Doctors at CSH rode that wave arguing that education was not only good for the masses, but good for the diseased mind:

"...not only should the body be treated to a healthful condition, but the mind also; and that teaching the insane is a powerful means of cure. There is little doubt that the day is near when the services of a well-qualified teacher upon each ward will be deemed as necessary as the physician or apothecary. Insane persons are in a second infancy, mentally; thoughtless, willful, acting without reason or self-control. Instruction, added to proper medical treatment, will do in degree the same for them that it does for children."

The school was so fruitful that CSH added a men's school in 1886. In a 1886 annual report, CSH patients testified to the success of the school:

A.B. : "They talk of sending me home, but I don't care much about it. I am studying reading, writing, arithmetic, grammar, geography and music. But Dutch is the best of all. I will write you a German letter before long."C.S. : "I am content to stay, for I am learning as much as I could in any other school. I am learning fractions."

How much of these testimonies were the patients' own words and how much was embellishment is impossible to know. Nonetheless, it appears that many patients enjoyed schooling, particularly the music and the arts and crafts classes.

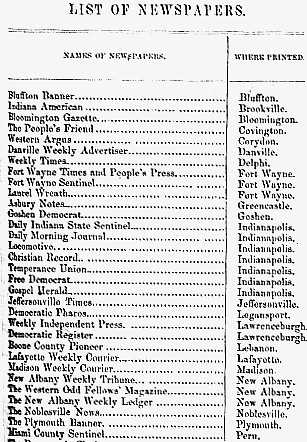

In connection with the school, CSH offered a library filled with wholesome books for the patients' enjoyment. Patients could also keep abreast on the latest news by perusing newspapers donated by newspaper publishers across the state.

- Partial List of Donated Newspapers (76.5 KB)

Patient Abuse

On the surface, CSH seemed to be a fairly pleasant place. A closer look, however, reveals some unsavory realities. For decades, the hospital confined its "worst inmates", those who screamed incessantly or who were bellicose, to the basement or the "dungeons" of the hospital. In 1870, CSH superintendent, Dr. Everts, was so appalled by the wretched condition of the dungeons that he reported it to the Governor:

"basement dungeons (are) dark, humid and foul, unfit for life of any kind, filled with maniacs who raved and howled like tortured beasts, for want of light, and air, and food, and ordinary human associations and habiliments..."

Worse yet, he exclaimed, the normal wards were "without adequate or intelligent provision for light, heat, or ventilation" and patients were forced to sleep on "beds all straw upon forbidding skeletons of iron". Repairs to the hospital structure were rarely made due to insufficient funds causing "abundant leakages" and rotten floors. Pantries and kitchen space were infested with cockroaches.

Unfortunately, Hoosier politicians did not heed Evert's words. In 1872, Dr. Everts, a frustrated and defeated man, resigned. But the work of Dr. Evert and like-minded reformers was not completely in vain: finally, in 1880, the legislature appointed an investigating committee to review charges of staff misconduct at state penal and charitable institutions.

"Indiana Crazy House," Albert Thayer, circa 1880s (99.7 KB)

"Indiana Crazy House," Albert Thayer, circa 1880s (99.7 KB)

Albert Thayer, a Civil War veteran, a publisher, and a CSH patient, shared Dr. Evert's reformist zeal. After being discharged from CSH in 1884, Thayer published exposes on CSH and other state institutions. Appalled by the poor treatment that he and other patients received at CSH, Thayer convinced former CSH patients to publish their stories in a broadside entitled, "The Indiana Crazy House," and in The Rough Diamond, a Thayer publication devoted to helping workers and the poor of Indiana.

"Indiana Crazy House, " page 3 (66.8 KB)

Thayer attributed most abuses to politicians, both democrats and republicans, who provided insufficient funding for the hospital which, in turn, led to understaffing, the hiring of poorly trained help, patient abuse, and inadequate food for patients.

Albert Thayer's obituary, Indianapolis News, October 1, 1920(113 KB) In addition, Thayer sent pre-printed letters to churches across the state asking them to speak out against "the corruptions and abuses in the Indiana Hospital for the Insane and the State Prison South." Thayer, an active member of Post 165 of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R), also spurred a movement among G.A.R. members to end the poor treatment of Union veterans and their widows and orphans at state charitable institutions.

In addition, Thayer sent pre-printed letters to churches across the state asking them to speak out against "the corruptions and abuses in the Indiana Hospital for the Insane and the State Prison South." Thayer, an active member of Post 165 of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R), also spurred a movement among G.A.R. members to end the poor treatment of Union veterans and their widows and orphans at state charitable institutions.

CSH Medical Attendants, early 1900s

CSH Medical Attendants, early 1900s

Fortunately, in the 1880s and 90s, reform-minded superintendents and community activists successfully lobbied for more funding to improve the hospital's appearance. But patient abuse continued. Medical attendants, not physicians, continued to be the primary care takers. Due to the low wages and the long hours the hospital offered, CSH was unable to attract high-caliber, well-trained personnel. Some did care for the patients with compassion, but many treated patients horribly. Attendants were known to hit patients, lock them in closets, and restrain them in bed for long periods of time. Many would punish patients if they spoke to one another, silencing them for hours on end.

The attendants, however, were not completely to blame. Abuses occurred, in part, due to understaffing and poor training. The widely-held, nineteenth-century belief that the mentally ill could control their actions and were at fault for their deviant behavior also factored into the abuse equation. At this time, attendants, as well as many Victorians, including some physicians, strongly believed that the mentally ill could be coaxed into normal adulthood through punishment, confinement, and "moral" training.

While our understanding and treatment of mental illness progressed in the twentieth century, patient abuse was an ongoing problem. At CSH, patient abuse continued to be a problem until its closure in 1994. In fact, lurid tales of patient abuse played a major role in the dismantling of Central State Hospital.

The Causes of Insanity

In the nineteenth century, the term insanity represented a broad spectrum of mental disorders as diverse as schizophrenia to the most severe of sociopathic disorders. What did nineteenth-century physicians think was at the heart of insanity?

Most antebellum physicians agreed that insanity was a disease of the brain and that examination of the brain tissues would reveal organic or functional abnormalities. Central State Hospital's (CSH) second medical superintendent, Richard Patterson, attested to this fact in his 1849 report to the State Commissioners:

mental derangement always depends upon either functional or organic diseases of the brain, and without such disease we see no derangement of the mind. The causes of this cerebral disease may be either physical or moral.

Accordingly, Dr. Patterson and his colleagues posited that "physical causes" of insanity were either direct afflictions, such as brain hemorrhaging or lesions, or indirect diseases, such as suppression of the menses or pulmonary disease, that, in time, damaged the central nervous system and eventually the brain.

But as Dr. Patterson noted, "moral causes" also contributed to the manifestation of insanity, and in an age when scientific medicine had not yet come to fruition, physicians naturally focused on the social and cultural forces causing insanity. Thus, CSH physicians typically attributed insanity to a host of social problems as diverse as domestic abuse to "Mexican War excitement" to Millerism (a religious sect founded on the belief that God's wrath would descend upon the earth before the millennium).

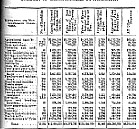

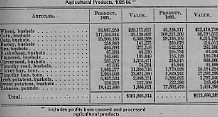

Causes of Insanity, Annual Report, 1853 [78 kb]

Many physicians suggested that these social problems were a direct result of the social, economic, and political instability wrought by Jacksonian democracy, civil war, and industrialization. As historian Charles Rothman has compellingly argued, unprecedented social and economic fluidity in the mid-nineteenth century compelled Americans, poor and rich, to aspire for more, and many physicians interpreted this climbing of the proverbial ladder as excessive and pathological behavior. Physicians were equally disturbed by the new political and social freedom engendered by Jacksonian democracy. As CSH superintendent James Athon opined:

insanity increases in the same ratio with the advancement of improvements, the accumulation of the luxuries of life, and the general spread of all those fanatical, religious and political principles which characterize the age.

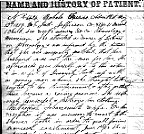

Entry from Central State Hospital Admission Book, 1858 [125 kb]

Fortunately, one of Dr. Patterson's predecessors, Dr. James Athon, required his medical staff to take detailed notes on the moral causes of each patient's mental illness, which appear in over fifty volumes of admission books and prescription books. These rich, detailed, and uncomfortably honest patient histories cast aspersions on many of the social, political, economic, and religious realities of nineteenth-century America.

Medical Treatment of Insanity

Entry from Central State Hospital Prescription Book, 1912 [44kb]

Nineteenth-century treatments for mental illness reflected physicians' understanding of the moral and physical causes of insanity. Like other nineteenth-century physicians, CSH doctors tailored treatment to address both the moral depravity and the underlying physical pathology of their patients. In hopes of altering the patients' physiological and mental state, CSH physicians administered liberal doses of narcotics, stimulants, emetics, and purgatives. A few exceptional superintendents, such as William Fletcher, demanded that the medical staff limit severe drug treatment to the worst cases and reduce the dosage of milder drugs for the masses of patients. Unfortunately, Dr. Fletcher's reforms in the early 1880s were often ignored by his successors.

While Dr. Fletcher and his nineteenth-century colleagues may have debated the merits of drug treatment, they did not debate the merits of moral therapy. CSH annual reports, prescription books, and patient histories illustrate the overwhelming support for moral therapy in both medical and political circles. Today, the notion of "moral therapy" conjures up images of wealthy philanthropists forcing their values and beliefs on the poor. In the context of Central State Hospital, this assertion rings true; moral treatment at CSH typically entailed impressing middle-class and protestant work ethics and mores on patients, most of whom were poor or struggling.

There were practical as well as ideological reasons for physicians' espousal of protestant and middle-class values. For most of the nineteenth century, physicians did not have the political or economic clout they have today. As a result, physicians attempted to curry the favor of politicians and their powerful constituents, in hopes of garnering financial support for their hospitals. To do this, physicians couched moral treatment in acceptable middle-class and upper-class terms. For CSH physicians, who were mostly middle-class and protestant, this did not require a large ideological leap.

In the early 1800s, middle-class values were synonymous with older, protestant beliefs that emphasized hard work and an orderly, religiously conservative lifestyle in an agricultural setting. Thus, in the nascent years of CSH, patients were encouraged to work on the hospital farm and were required to lead quiet, orderly lives separate from the chaotic world outside. This form of therapy also fit nicely into prevailing theories of insanity: if social, political, and economic freedoms were causing insanity, then it logically followed that severely limiting freedom in the context of the asylum would cure mentally-ill patients.

Summary of Hoosier Manufacturers/Industrialists, 1885-86 [120 kb]

By the second half the nineteenth century, however, a new, burgeoning middle-class, the nouveau riche, redefined its values to include behaviors and beliefs that were beneficial to industrial capitalism.

Hoosier Agricultural Products, 1885-86[83 kb]

And, now, the stakes were even higher: segments of the new middle-class were not only powerful and wealthy, but also embraced a reformist zeal and philanthropic spirit that far exceeded that of earlier generations. It became all that more important for CSH physicians to pander to middle-class reformers and philanthropists who were searching for a charitable outlet for their money and enthusiasm.

Central State Hospital Cannery, mid 1900s [94 kb]

To prove their commitment to the new middle class values, CSH physicians attempted to engender in their patients a certain discipline and value system that fostered an industrial work ethic. Healthier patients were required, not encouraged, to follow strict work schedules, that included producing garment piece work and other products that could be sold to outside factories. In the early twentieth century, CSH instituted an "occupational therapy" program that entailed patients working with hand/foot operated machines to create products for no compensation. A few decades later, CSH built a cannery for patients, indicating that the hospital's full integration into the industrial world had been achieved. Importantly, the work therapy program served another equally imperative function: it provided additional moneys to supplement unreliable state funding that ebbed and flowed with the changing political tides.

Regulated work, however, was not enough. A "well-regulated" diet, a highly "regimented" morning and evening schedule, the reading of wholesome books from the hospital's "selected library", and the partaking in "mild and innocent amusements" were sure cures for mental illness and a sure way of inculcating white middle-class mores. In retrospect, the living conditions at CSH may seem overly oppressive and the motives of the physicians questionable, but this highly structured environment did offer solace to many patients, particularly in a period when few other cures existed.

Holding Chair, 1800's [36 kb]

If the moral universe of CSH was not sufficient to modify behavior, detention, physical restraints, and "baths" were used. Medical attendants employed cold and hot "baths" to calm patients, to force them into submission or to punish them. Attendants confined more violent patients to their beds or to holding chairs with mechanical restraints. Still others, the worst cases, were confined to the dark, dungeon-like basements of the hospital.

Many of the more harsh treatments fell out of vogue in the 1880s and '90s as compassionate superintendents and reformers, like William Fletcher and Nellie Bly, and physicians imbued with the scientific spirit, like CSH superintendent George Edenharter, pushed for change.

Central State Medical Staff: An Introduction

By the late nineteenth century, an enlarged and sophisticated CSH medical staff personified the transformation of orthodox medicine from a theoretical art to a laboratory-based science. Several important medical developments spurred this transformation and, in turn, initiated changes in both medical treatment at CSH and the makeup of its medical staff.

The most important development, the introduction of the germ theory, transformed the way physicians approached disease. Rather than viewing the body holistically and attributing diseases to social and moral forces, physicians began to imagine disease as microscopic germs invading certain organs or groups of organs. This new disease paradigm, coupled with the movement for professionalization in medicine, encouraged the development of medical specialization, laboratory research, and institutionalized clinical training.

New Additions to the CSH Staff

Specifically, the emergence of medical specialization had a profound impact on CSH. For the first time, CSH enlisted the help of medical specialists, including a gynecologist, a dentist, a pathologist, and several physicians who had specialized in the "diseases of the mind".

CSH first hired a female gynecologist. In 1883, Superintendent William Fletcher, a caring and progressive physician, recommended that CSH employ a "lady" practitioner who was well-versed in "female ailments and afflictions":

"...it would be a comfort to every parent, brother, sister, to know that their afflicted loved ones who were insane from the fact of being a woman, were to fall into the hands of a cultured and refined female physician."

To support his case, Fletcher touted a well-regarded, nineteenth-century hypothesis that suggested that insanity in women was caused by ailments peculiar to the female reproductive system. In hindsight, such theories appear sexist. Yet, it was the very notion that women were biologically different and therefore, socially different than men, that compelled Fletcher to actively promote "woman's" physicians.

Theories of women's and men's social and biological uniqueness underscored separate sphere ideology which, ironically, was exploited by women professionals and male sympathizers, like Fletcher, to introduce women into professions previously closed to them. For Dr. Fletcher, as well as many other Victorians, women physicians were the best qualified to treat female patients with reproductive problems because Victorian women, who were modest, scrupulous and moral beings, should not be corrupted by male physicians performing pelvic examinations. Victorian sensibilities and a compulsion to protect the separation of the sexes drove women right into men's shoes.

In December 1883, Dr. Fletcher got his wish: Sarah Stockton, a graduate of the Women's Medical College of Philadelphia and a native of Tippecanoe County, joined the CHS staff. Dr. Fletcher was so pleased with her work -- "Dr. Sarah Stockton has continued her duties with perfect satisfaction and good results" -- that he featured her report of the "special work in the Department of Women" in the hospital's 1885 annual report to the board of trustees.

In a period when few female physicians were permitted to perform intrusive procedures in male-dominated hospitals, Dr. Fletcher encouraged Dr. Stockton to operate on female patients when necessary. While Fletcher may have hired Dr. Stockton based on his own preconceived ideas about the female sex, he gave Sarah the opportunity to shine in a man's world. By hiring Dr. Stockton, Fletcher also made it legitimate for other superintendents to hire female physicians for the women's department, which they continued to do until 1927.

Sarah Stockton with Male Colleagues, CSH Pathology Departmental Library, 1910 (57.2 kb)

Soon after Dr. Stockton began her tenure at CSH, pathologist E.F. Hodges joined the staff in 1885. The hiring of Dr. Hodges set a series of events in motion that transformed CSH from a custodial facility into a treatment and research center. For the first time, CSH medical superintendents began to take a new interest in the systematic study of the physical causes of mental illness.

Sarah Stockton, MD (1842-1924)

Sarah Stockton was born on a farm in Tippecanoe County in 1842. After running a boarding house with her sister for many years, she embarked on a medical career, receiving a medical degree from the esteemed Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1882. While at the Woman's Medical College, Sarah devoted much of her time to writing a doctoral thesis on the history of insanity and the treatment of mental illness.

An abiding interest in the study of mental illness brought Dr. Stockton to Central State Hospital (CSH) in December 1883. Primarily, she served as a general practitioner on the women's wards, treating female patients for a wide range of physical and mental ailments. According to Superintendent William Fletcher, however, her job was to treat female patients suffering from reproductive ailments peculiar to their sex. Many a physician, including Fletcher, thought that reproductive ailments could cause or exaggerate mental illness in women and that women physicians were uniquely qualified to treat gynecological disorders.

Dr. Stockton, who was as fully immersed in Victorian culture as her male counterparts, seemed to agree with Dr. Fletcher's assertions. Possibly, she agreed with Fletcher to keep her job, but given her close personal relationship with Fletcher and the general tenor of all her writing, it appears that she, too, subscribed to the theory that gynecological ailments could cause insanity. Self-preservation may have compelled Dr. Stockton to support the argument that only women should perform pelvic examinations on women, but Stockton probably agreed with this argument on a philosophical level as well.

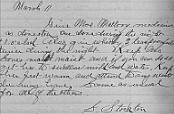

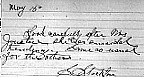

Medical Treatments Prescribed by Dr. Stockton (75.4 kb)

According to her reports, Stockton's primary job was to provide "treatment for the relief of derangements and diseases of the pelvic organs by which both the mental and physical health of insane women might be benefitted." Stockton, however, was cautious not to attribute all mental illness in women to reproductive disorders. Yet, she still believed that this class of disorders could cause insanity. She noted in a 1885 report that "irregularities of menstruation are common among insane women, but I do not believe that in every instance it takes part in causing insanity."

Medical Treatments Prescribed by Dr. Stockton (29.6 kb)

While Dr. Stockton treated women with gynecological troubles, she also spent much of her time treating common afflictions like colds, sore throats, and upset stomachs. To treat these ailments, Dr. Stockton performed medical procedures ranging from administering drugs to surgery.

In 1888, Dr. Stockton left Central State Hospital to work at Dr. Fletcher's new sanatorium in Indianapolis. Later in 1891, the managers of the Indiana Reform School for Girls and Woman's Prison appointed Dr. Stockton as the institution's physician. Sarah, alone, administered medical treatment, including surgical treatment, to the entire inmate population.

In 1899, Dr. Stockton once again returned to Central State Hospital. This time she stayed until her health declined in 1923. In addition to her hospital duties, Stockton served on the powerful Board of State Charities from 1904 to 1907. After forty years of public service, Dr. Stockon died from a severe heart attack on March 13, 1924.

Looking back on her career, Dr. Stockton was an amazing woman. She never allowed sexism or financial hardship to stand in her way. As a public servant, Sarah lived on a meager salary, but her commitment to serving Indiana's underprivileged gave her the fortitude to endure hard, long hours at Central State Hospital. Late in her career, she may have been accused by some co-workers as being a "millstone" and a malingerer, but it was her old age and poor health that encouraged these remarks. For most of her career, Dr. Sarah Stockton had served patients at Central State Hospital with great heroism, dedication, and empathy.

Central State's Medical Staff and the Emergence of Scientific Medicine: 1890-1920

George Edenharter, CSH Superintendent from 1893-1923 (32.1 kb)

In the early 1890s, Superintendent Edenharter, seeking recognition from the medical community and hoping to expand medical research at CSH, lobbied for funds to construct a hospital pathology laboratory. Edenharter was a well-connected man who had served on the city council for four years and had run for mayor. Due to the paucity of legislative records from this period, the particulars of how funding was secured and funneled to CSH for the construction of the pathology laboratory is unclear.

It is reasonable to assume, however, that Edenharter, a man of considerable political clout, played a significant role. Edenharter skillfully married the pathology department with state medical education. A new state-of-the-art pathology department would make CSH the Indiana center for the scientific study of mental illness. Medical students from the Medical College of Indiana and the Central College of Physicians and Surgeons, as well as practicing physicians, would be invited to attend classes at CSH. In turn, physicians educated at CSH would provide better treatment for the mentally-ill patients in their care and most importantly, would possess the knowledge to diagnosis mental illness in the early stages and thus, strike a cure. If early diagnosis meant higher rates of recovery, then fewer mentally-ill people would become wards of the state. In the long run, Edenharter argued, the pathology department would save Indiana tax dollars.

Edenharter was victorious. In 1896, the pathology building, complete with an amphitheater, pathological museum, dissection and autopsy rooms, library, photography room, and three laboratories, was opened for scientific research.

CSH's Pathology Department, early 1900s (74.8 kb)

Did the pathology department live up to Edenharter's expectations? The department did fill its mission to educate Hoosier physicians, but failed to translate patient autopsies and preserved specimens into original research and progressive treatment.

Partial List of Courses Offered at CSH, 1906-07 (78 kb)

Partial List of Courses Offered at CSH, 1906-07 (78 kb)

Dr. Edward J. Kempf, a CSH physician, attested to the failure of the pathology department in his disturbing account of conditions at CSH in 1912. When asked by the Legislative Visiting Committee what influence the pathology department had on the rest of the hospital, Kempf exclaimed:

"There are four pathology reports. Good if well done, but the last one not accurate. Padded. Reports of autopsies put in that, that are not scientific, they are so thoroughly incomplete. The great part of the report is devoted to scientific treatment of patients, not one whit of it used in the institution. Letters from eminent men (lauding CSH) are based on the reports and not on the work the institution is doing. The Hospital is utterly devoid of any scientific interest from superintendent on down."

Kempf did exclude Dr. Max Bahr and Dr. Everman from this statement, as they were also struggling to bring science to CHS. But unlike Kempf who was fired for "instituting a revolutionary movement against the management", Bahr's and Everman's reticence insured they would keep their jobs.

While we could dismiss Kempf's statement as hyperbole, patient allegations of staff misconduct and poor treatment suggest that Kempf was probably correct in many of his assertions. CSH, however, was not unlike most early 20th-century institutions for the mentally ill, which similarly struggled to provide humane, progressive treatment with limited funds and limited knowledge. Even Kempf admitted that the problems plaguing CSH were also plaguing other mental health hospitals across the country.

While Edenharter's great dream of making CSH a center for scientific research and cutting-edge treatment was never realized during his tenure, the pathology department did attract exceptional physicians, like Max Bahr and Walter L. Bruetsch, who brought his dream to fruition. Besides being a compassionate caretaker, Dr. Bahr, a CSH superintendent for 29 years, created an atmosphere at CSH that was conducive to scientific exploration. Dr. Bahr insisted that the pathology department serve the purpose it was intended for:

" A department of pathology and research is also a necessary adjunct to every state hospital because it stimulates the members of the staff to greater professional effort. It creates a demand for accurate case and clinical histories. This requires more attention to the individual patient. It incites to study and systematic investigation by having on hand the requisite appliances...."

To assist CSH in its scientific endeavors, Dr. Bahr established an occupational therapy program, an out-patient department, a social service department, an X-ray department, and a nursing department.

Max Bahr, CSH Superintendent from 1924-1951 (37.5 kb)

Under his watch, one of the most famous scientists ever to work for CSH, Walter L. Bruetsch, introduced the method of using malaria to treat syphilis. Dr. Bruetsch received international acclaim for his research. Today, using one dangerous, infectious disease to treat another seems scary, even fantastical. But in the days before the discovery of penicillin and other antibiotics, harsh treatments, like the use of arsenic compounds or malaria to control the effects of sexually transmitted diseases, held more hope than other less radical treatments.

Unfortunately, shining stars, like Dr. Bruetsch, could not overcome the many obstacles CSH faced in the 20th century. Insufficient funding, mismanagement, over-crowding, and political infighting created problems for CSH and many other state hospitals. While CSH's history was full of humane people with good intentions, lurid but true tales of patient abuse and corruption overshadowed their accomplishments.

In the 1960s, the American psychiatric community recognized that large mental health institutions were neither particularly effective nor good for their patients; with help from state and federal politicians, they began to de-institutionalize the mentally ill. For many, de-institutionalization was a positive and a life-saving event, but for the many severely mentally-ill denizens wandering our country's streets, it was a dismal failure.