"Black Day"

February 24, 1887: The “Black Day” of the Indiana General Assembly

While modern politics has its share of issues, few current events compare to the government breakdown and physical violence seen in Indianapolis on February 24, 1887. Dubbed by the press as “The Black Day of the General Assembly,” the event requires some knowledge of 19th century politics to understand.

Governor Isaac P. Gray made his first big impact in politics in 1869, when as Republican president pro tempore of the State Senate he locked the Senate in its chambers in until the 15th Amendment was passed. The amendment was opposed by the Democratic Party at the time, and the Democratic Assembly members planned to leave the chamber to deny a quorum, preventing any business from being completed. While the move made Indiana the last state needed to pass the amendment, the impact on Gray’s career, both positive and negative, would be felt for decades.

In 1887 Gray was the Governor of Indiana, but had his sights set on Benjamin Harrison’s soon to be vacant U.S. Senate seat. Since 1869 he switched parties; first to the Liberal Republicans, a short-lived offshoot, and then to the Democratic Party. Before the Seventeenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, U.S. Senators were elected by their state legislature, and were frequently drawn from that body or the state’s executive branch. Gray intended to pursue the nomination and be replaced by Lieutenant Governor, Mahlon Dickerson Manson. However, Gray’s Republican opponents, as well as Democrats that remembered his actions as a Republican from 1869 worked to convince Manson to resign, leaving Gray without someone to take his place if he won election to the Senate.

Gray met with the Attorney General Francis T. Hord and determined that the Indiana Constitution allowed them to call for the election of a new lieutenant governor in the off-year 1886 election. Gray favored the Democratic candidate, John C. Nelson, as he felt his election as lieutenant governor would make the Democrats in the Assembly more likely to support his Senate bid. But Nelson was upset by the election of Republican Robert S. Robertson (note: under the Indiana Constitution in effect at this time, a governor and lieutenant governor ran separately and did not need to be of the same political party).

Democrats declared the election unconstitutional and immediately set about challenging it in court. Robertson took his oath of office on the 10th of January but was prevented from taking his seat by a Marion County Court ruling. In the meantime, the Senate elected Alonzo G. Smith are acting president pro tempore and continued with Assembly business. The ruling would stay in place until February 23rd, when the Indiana Supreme Court declared the election valid and ordered him seated in the Senate.

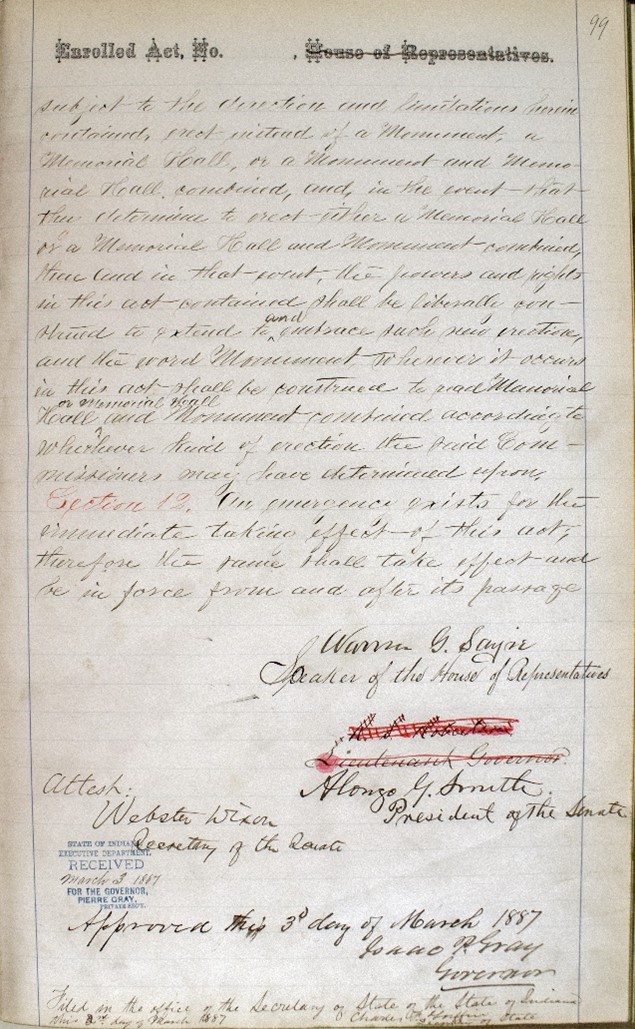

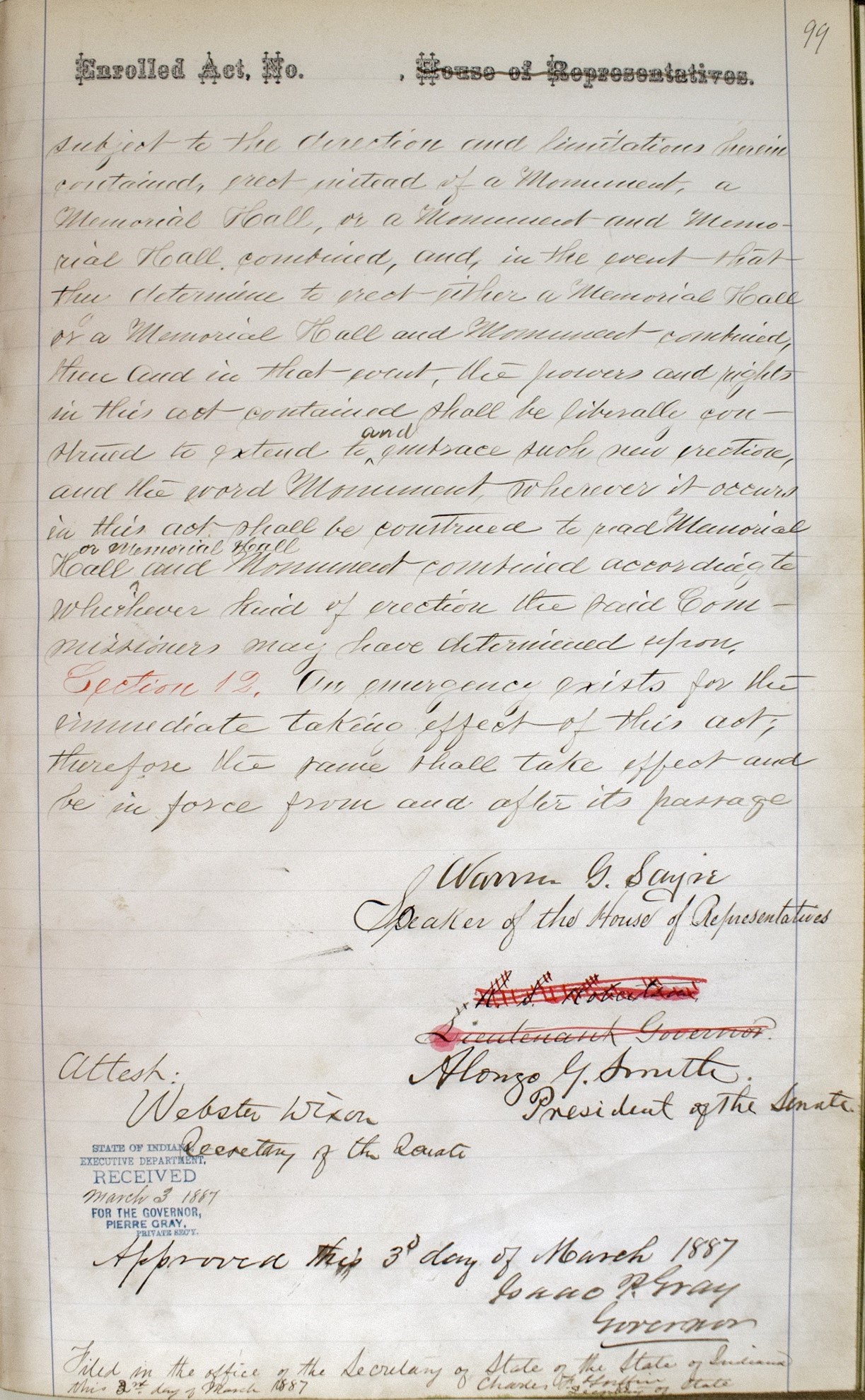

But the Democrats were far from through with their opposition. The image here is the final page for the 1887 act creating the Indiana Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument. At the bottom of the page, we see can see two lieutenant governors’ signatures; Robertson’s struck out and Smith’s written in its place. This is because Robertson was physically prevented from taking his seat, and Smith ordered him ejected and the door barred behind them. These actions sparked intermittent but widespread physical fights between the opposing parties in the Statehouse for most of the rest of the day, even spilling out to the surrounding streets and businesses. It was eventually calmed by the Governor’s call for police assistance from the city and county, and Robertson’s own calls to end the violence. As a result of the Senate’s refusal to seat Robertson, the House refused to communicate with them for the rest of the session, essentially ending the business of the session, which only met once every other year at the time.

The Black Day would go on to become one of the examples of corrupt party politics held up by proponents of the 17th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which changed the election of Senators to a popular vote in 1912.

This blog post was written by Reference Archivist Keenan Salla.