Location: Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site, 1230 N. Delaware St., Indianapolis (Marion County, Indiana) 46202

Installed 2017 Indiana Historical Bureau, Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site, and the Caroline Scott Harrison Chapter NSDAR

ID#: 49.2017.4

![]() Visit the Indiana History Blog to learn more about Harrison's life and work.

Visit the Indiana History Blog to learn more about Harrison's life and work.

Text

Side One

First Lady Caroline Harrison

Caroline Scott Harrison (1832-1892), wife of President Benjamin Harrison, advocated for the arts and worked to expand women’s influence outside the home. She was active in charity work in Indiana and Washington, D.C., including 30 years on the Indianapolis Orphans Asylum board of managers. She campaigned to gain women’s admission to Johns Hopkins Medical School, 1890.

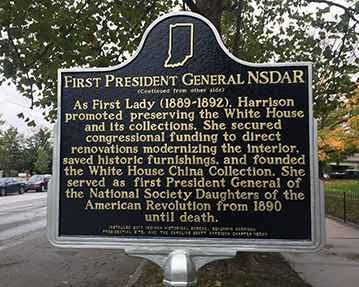

Side Two

First President General NSDAR

As First Lady (1889-1892), Harrison promoted preserving the White House and its collections. She secured congressional funding to direct renovations modernizing the interior, saved historic furnishings, and founded the White House China Collection. She served as first President General of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution from 1890 until death.

Annotated Text

Side One

First Lady Caroline Harrison

Caroline Scott Harrison (1832-1892), wife of President Benjamin Harrison,[1] advocated for the arts[2] and worked to expand women’s influence outside the home.[3] She was active in charity work in Indiana[4] and Washington, D.C.,[5] including 30 years on the Indianapolis Orphans Asylum board of managers.[6] She campaigned to gain women’s admission to Johns Hopkins Medical School, 1890.[7]

Side Two

First President General NSDAR

As First Lady (1889-1892), Harrison promoted preserving the White House and its collections.[8] She secured congressional funding to direct renovations to modernize the interior,[9] saved historic furnishings[10] and founded the White House China Collection.[11] She served as first President General of National Society Daughters of the American Revolution from 1890[12] until death. [13]

[1] “Caroline Scott Harrison,” gravestone, accessed Find A Grave; Marriage Record for Caroline Lavinia Scott and Benjamin Harrison, 1853, source 1055.000, U.S. and International Marriage Records, 1560-1900, Provo, UT, accessed Ancestry Library.

Caroline Scott Harrison’s gravestone in Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis, Indiana states she was born October 1, 1832 and died October 25, 1892. It notes she was the “beloved wife of Benjamin Harrison,” and that the two were married October 20, 1853. Marriage records for Caroline Lavinia Scott and Benjamin Harrison show both were married in Ohio in 1853.

[2] “City News,” Indianapolis News, September 27, 1880, 3, Indiana State Library (ISL) microfilm; “Loan Exhibition: 1st Annual Exhibition of the Art Association of Indianapolis,” November 7-30, 1883, accessed Indianapolis Museum of Art; “The Fancy Work Exhibition,” Indianapolis News, January 11, 1887, 4, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles (HSC); “Pottery Display: A Very Fine Exhibit,” Indianapolis News, December 14, 1887, 1, accessed HSC; “A Home for the President: A Chat with Mrs. Harrison About the White House and What it Needs,” Evening Star [Washington, D.C.], July 20, 1889, 9, accessed Newspapers.com; National Art Association, Smithsonian Institution, Catalogue of the First National Loan Exhibition of the National Art Association (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1892), accessed Smithsonian Libraries; “Art Notes,” The Critic, April 16, 1892, 230, accessed American Periodicals; Harriet McIntire Foster, Mrs. Benjamin Harrison: The First President General of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (First Honorary State Regent of the Daughters of the American Revolution of Indiana, 1908), 12-13; William Kloss, Art in the White House: A Nation’s Pride (White House Historical Association, National Geographic Society: Washington, D.C., 1992), 37-38; Kimberly Orcutt, “Buy American?: The Debate over the Art Tariff,” American Art 16, no. 3 (Autumn 2002): 82-83, 86, accessed University of Chicago Press Journals; Caroline Lavinia Scott Harrison, n.d. Sailboat, watercolor, Sarasota, FL, James M. Fetheroff Collection, accessed Smithsonian; Caroline Lavinia Scott Harrison, n.d., 40 Watercolor Paintings. Watercolor. Indianapolis, Indiana: President Benjamin Harrison Memorial Home, accessed Smithsonian; Caroline Lavinia Scott Harrison, ca. 1889-1892, Flowering Dogwood, watercolor on paper. Washington, D.C.: White House, accessed Smithsonian.

Harrison became involved in arts advocacy in Indianapolis and later used her position as First Lady to promote the arts on a national scale. Harriet McIntire Foster, one of Harrison’s earliest biographers and an acquaintance of Harrison, noted that painting was Harrison’s “favorite pursuit.” According to Foster, Harrison had a studio on the north side of her home where she painted with water colors and on china (for more on Harrison and china painting, see footnote 9). At least forty-two of Harrison’s original watercolors remain. Foster recalled in her biography, “Mrs. Harrison was always most generous in asking congenial art students to share her studio, with whom she insisted upon sharing her most valuable materials.” Harrison loaned her work, including china paintings and embroidery, to the first Art Association of Indianapolis exhibits in the 1880s. The Art Association’s efforts was to “encourage and develop an abiding interest in all matters pertaining to art in Indianapolis.” The Art Association of Indianapolis, organized in 1883 after an art lecture hosted by educator and women’s rights activist May Wright Sewall, hosted important art exhibitions and pioneered formal art education in Indiana. The Association greatly influenced the development of the fine arts in Indiana and fostered the growth of art appreciation in its citizens. The organization also created a museum and a school that evolved into the Herron School of Art and the Indianapolis Museum of Art, thus fulfilling the goals it established in its 1883 Articles of Incorporation “to cultivate and advance Art in all its branches; to provide means for instruction in the various branches of Art; to establish for that end a permanent gallery, and also to establish and produce lectures upon subjects relevant to Art.”

As First Lady, Harrison advocated for the federal government to place more emphasis on fine art. In her plans to expand the White House (see footnotes 9 and 10), she included a large gallery of historical paintings. She told the Evening Star “this government has reached that point where it should give more attention to the fine arts—that is, a judicious expenditure for works of merit.” She supported the addition of paintings to the White House’s fine arts collection, including the first example of a non-portrait piece purchased for the White House by the federal government, a watercolor by James Henry Moser. Art historian William Kloss emphasized that Harrison’s plans and actions set precedent for the introduction of a professional curator to care for the White House’s art collection during the Kennedy Administration seventy years later. In 1892, she became Honorary President of the National Art Association, an organization whose goal was to exempt imported works of art from taxation. In 1883, the tariff on foreign art had tripled to 30% and by 1890, the United States had the highest tariff rates of any developed nation, which led to a national debate about the art tariff. Eventually, protests from the art community, including efforts from the National Art Association, which included Harrison and many prominent American artists, like Albert Bierdstadt and William Merritt Chase, resulted in the lifting of the tariff.

[3] “Woman’s Medical Fund: Another Meeting to Encourage the Great Movement,” The Baltimore Sun, November 1, 1890, 6, accessed ProQuest; Rachel Foster Avery, ed., Transactions of the National Council of Women of the United States (Executive Board of the National Council of Women: Washington, D.C., 1891), 10, 364, accessed Library of Congress; Caroline Scott Harrison, “Address to the First Continental Congress,” February 22, 1892, accessed Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR); “The President’s Wife: Some Personal Characteristics of Mrs. Benjamin Harrison,” The Baltimore Sun, October 14, 1892, 8, accessed ProQuest ; “Caroline Scott Harrison,” The Woman’s Tribune, iss. 27 (October 29, 1892): 1, accessed Nineteenth Century Collections Online; “In Memoriam,” American Monthly Magazine 1, no. 5. (November 1892): 511, accessed NSDAR; Shawn J. Parry-Giles and Diane M. Blair, “The Rise of the Rhetorical First Lady: Politics, Gender Ideology, and Women’s Voice, 1789-2002,” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 5, no. 4 (Winter 2002): 574, accessed JSTOR; Nancy Hendricks, America’s First Ladies: A Historical Encyclopedia and Primary Document Collection of the Remarkable Women of the White House (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2015), 186; Woden Sorrow Teachout, “Forging Memory: Hereditary Societies, Patriotism and the American Past, 1876-1898,” (PhD. Diss., Harvard University, May 2003), 82, 95, accessed ProQuest.

The American Monthly Magazine, the official magazine of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, noted in Harrison’s obituary she “did not limit the exercise of her virtues to the circle of domestic and social duties.” Instead, “she was prominent, during her whole life, in many good works, and in Washington was a leading spirit in various charities.” Newspaper articles remark that Harrison was not a suffragist, but still advocated for women’s education and activity outside of the home, often through philanthropy and charity work. The Baltimore Sun interviewed Mrs. John V.L. Findlay, a relative of the Harrison’s, in 1892. Mrs. Findlay told the Sun that Harrison “takes a keen interest in the various movements for the advancement of women, not along the line of the ‘woman’s rights’ question, but whatever tends toward their educational advantage.” Harrison’s obituary in the Woman’s Tribune in 1892 stated “although she [Harrison] had not entered into the woman suffrage movement, she was deeply interested in all that pertains to woman’s advancement.”

Harrison particularly lent her name as First Lady to several organizations dedicated to expanding women’s opportunities and influence, which not only showed her personal interest, but also lent these organizations credibility and prominence. For example, in 1890, she became head fundraiser in Washington, D.C. to establish women’s admission, on equal terms as male applicants, to Johns Hopkins Medical School (see footnote 7). Harrison also became the first President General of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution in 1890 (see footnote 11), an organization dedicated to recognizing and preserving the history of women’s impact and patriotism during the Revolutionary War. The National Society formed after the Sons of the American Revolution decided not to accept female members in 1890 and asked Harrison to serve as President to add credibility to their organization. Harrison gave a speech, what some historians and scholars credit as the first public recorded address given by an acting First Lady, during the DAR’s First Continental Congress. Harrison emphasized in her speech:

Since this Society has been organized, and so much thought and reading directed to the early struggle of this country, it has been made plain that much of its success was due to the character of the women of that era. The unselfish part they acted constantly commends itself to our admiration and example. If there is no abatement in this element of success in our ranks I feel sure their daughters can perpetuate a society worthy of the cause and worthy of themselves.

In 1891, the National Council of Women of the United States, whose members contained eleven of the “most important national organizations of women in the country” that are interested in “the advancement of women’s work in education, philanthropy, reform, and social culture,” met in Washington, D.C. Harrison extended an invitation for the National Council and all delegates and members to attend a reception at the White House. She received them February 26, 1891, lending her name as First Lady to the cause. Harrison’s obituary in the Women’s Tribune also noted that “on one occasion” Mrs. Harrison had met with Susan B. Anthony, who explained her desire for woman suffragists to have a voice in the management of the World’s Fair. The obituary noted that “while she [Harrison] could not make any public demonstration of her moves, she promised to use her influence with Senators and Congressmen to provide for this recognition of woman. Who can tell how largely the honorable position assigned to women in the management of the Columbian Exposition may be due to her word fitly spoken.”

[4] Katherine E. Badertscher, “Organized Charity and the Civic Ideal in Indianapolis, 1879-1922,” (Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, May 2015), accessed ProQuest; “Address of the Ladies’ Patriotic Association of Indianapolis to the Women of Indiana,” Indiana State Sentinel, October 23, 1861, 3, accessed HSC; “Letter from the Seventieth,” Indiana State Sentinel, September 8, 1862, 4, accessed HSC; “Ladies Committees for the Sanitary Bazaar,” Indianapolis Star, September 17, 1864, 3, accessed Newspapers.com; Catalogue of Church Officers and Members, of the First Presbyterian Church of Indianapolis, Indiana, July 21, 1866, First Presbyterian Church Time Capsule Collection, 1839-1902, M 0771, Box 1, Folder 13; “Home for Friendless Women,” Indianapolis Daily Journal, February 4, 1867, 8, accessed ISL microfilm; “Indianapolis Benevolent Society,” Daily State Sentinel, November 27, 1868, 2, accessed HSC; “Relief for the Sufferers,” Daily State Sentinel, October 7, 1869, 4, accessed HSC; “The Sunday School Work,” Indianapolis News, October 28, 1872, 3, accessed HSC; “The State Temperance Convention,” Indianapolis News, May 18, 1875, 2, accessed HSC; “Appeal for Help,” Indianapolis News, June 16, 1875, 1, accessed HSC; “Centennial Matters,” Indianapolis News, July 21, 1875, 1, accessed HSC; “Appointment of Soliciting Committee,” Indianapolis News, October 12, 1875, 4, accessed HSC; “Benevolent Society,” Indianapolis News, November 29, 1878, 3, accessed HSC; “The Women’s Foreign Missionary Society of the First Presbyterian Church,” March 31, 1879, First Presbyterian Church Time Capsules Collection, 1839-1902, M 0771, Box 3, Folder 2; Indianapolis Benevolent Society Minute Book, 1879-1918, BV 1178, 7, 68, The Family Service Association of Indianapolis Records, 1879-1971, M 0102, Indiana Historical Society; “The Flower Mission Fair,” Indianapolis News, “Standing Committees of the Board,” November 26, 1880, 4, accessed HSC; “Standing Committees of the Board,” Indianapolis News, July 16, 1887, 8, accessed HSC; Joan S. Bey, “What Ever Became of Annie Brown?,” Indianapolis Retirement Home Records, 1867-1980, M 519, Box 9, Folder 2; Board of Managers Minutes, BV 2513, Indianapolis Retirement Home Records, 1867-1980, Indiana Historical Society; “Retirement Home Started in 1867 Will Close this Fall,” Indianapolis Star, July 4, 2003, B2, accessed Newspapers.com.

Harrison was a member of the First Presbyterian Church, which was connected to the largest charity organizations in Indianapolis in the 19th century, such as the Indianapolis Benevolent Society and the Charity Organization Society. Members of the Indianapolis Benevolent Society, organized in 1835, “served as donors, fundraisers, friendly visitors and distributors of aid,” according to Katherine E. Badertscher. A gentleman and lady member were each assigned to a certain district in the city to identify those needing assistance, learn about their needs, and counsel on home care, employment, and religious practice, and solicit donations in that area. Caroline and Benjamin Harrison joined the First Presbyterian Church in 1854. Caroline became involved in teaching Sunday school, the Ladies Foreign Missionary Society, and served on one of the visiting committees for the Benevolent Society.

During the Civil War, Harrison joined the Ladies Patriotic Association and the Ladies Sanitary Committee in Indianapolis, organizations dedicated to providing relief and supplies to soldiers. During this time, Harrison also appears to have started her thirty year-long work with the Indianapolis Orphans Asylum (see footnote 7). After the Civil War, she also became one of first women involved with a new charity, the Home for Friendless Women. After the war, many women were left widowed and without resources. Often, they came to Indianapolis hoping they would find their spouse detained in the Indiana State Capitol, but often were not successful. During the war, new military installations near the capital drew prostitutes to the city for work. After the war, the women lost clientele and funds to care for themselves. Caroline became one of the volunteers that secured funds to organize a permanent home for such needy, single women. Harrison was part of a band of prominent Indianapolis women who established the home, called the Home for Friendless Women, and served briefly on the board in 1868. The Home for Friendless Women served many women throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, operating until 2003 under the name Indianapolis Retirement Home.

In 1879, the Charity Organization Society of Indianapolis was founded. Benjamin Harrison participated in the founding meeting. The Indianapolis Benevolent Society became a co-operating agency. According to Badertscher, “the merger created the largest private, nonprofit, social service organization in Indianapolis.” The Charity Organization Society and the Indianapolis Benevolent Society became the central hub that supervised many major charities in Indianapolis, including the Indianapolis Orphans Society, the Flower Mission, the German Benevolent Society, the Friendly Inn Wood Yard, the Colored Orphan Asylum, the Home for Friendless Women, St. Vincent’s Hospital, Little Sisters of the Poor, City Hospital, City Dispensary, Children’s Aid Society, Maternity Society, and others.

Through her connections to the Indianapolis Benevolent Society and the Charity Organization Society, it appears Harrison became involved with many temporary relief funds and events in the city. Using digitized newspapers on Newspapers.com and Hoosier State Chronicles, IHB staff found that Harrison was involved in the following activities: raising funds to provide relief for victims of a local boiler explosion at the fairgrounds in 1869, assisting with organizing the Centennial Celebration and the State Temperance Convention in 1875, participating in a soliciting committee raising funds to provide relief for a grasshopper plague in Missouri in 1875, and helping with Flower Mission fairs.

[5] “Ladies’ Aid Association,” National Republican [Washington, D.C.], April 4, 1882, 4, accessed Newspapers.com; “The Garfield Hospital,” Evening Star [Washington, D.C.], January 16, 1884, 4, accessed Newspapers.com; “Officers Elected,” Evening Star, January 21, 1885, 4, accessed Newspapers.com; “Society Notes,” Evening Star, March 24, 1887, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Social Matters,” Evening Star, November 28, 1888, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; “Mrs. Harrison’s Good Works,” Democrat and Chronicle [Rochester, NY], December 2, 1888, 5, accessed Newspapers.com; “In Memoriam,” American Monthly Magazine, 511; Foster, Mrs. Benjamin Harrison, 20; Kate Scott Brooks, “Memories of Our First President General,” n.d., accessed Caroline Scott Harrison Chapter, Indianapolis, Indiana, DAR; “Garfield Memorial Hospital: Training School for Nurses. Alumnae Association,” accessed SNAC.

Harrison was also known for working closely with charities while living in Washington D.C. from 1881-1889 while Benjamin Harrison served as a US Senator, and continued to support them as First Lady. Her obituary in the American Monthly Magazine, the Daughters of the American Revolution’s publication, noted that Harrison “was prominent, during her whole life, in many good works, and in Washington was a leading spirit in various charities, and made special efforts on behalf of Garfield Hospital.” Likewise, her niece Kate Scott Brooks wrote that Harrison was “active in church and charity work here, being on the board of the Garfield Hospital and in several organization in the Church of the Covenant.” Newspaper articles indicate that Harrison was part of the Ladies Aid Association of Garfield Memorial Hospital as early as 1882 and served as second vice president in 1884. The hospital, which opened in 1882, was the first general hospital in Washington, D.C. Newspaper articles also show that Harrison was part of the Washington City Orphans Asylum, serving on the board of managers in 1885 and 1887.

[6] “Messrs. Woolley, Stewart and McNaught,” Indiana State Sentinel, March 13, 1856, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Indianapolis Orphans Society,” Indianapolis Daily Sentinel, May 20, 1862, 3, accessed HSC; “Orphan Asylum,” Indianapolis Daily Sentinel, June 3, 1864, 3, accessed HSC; “The Regular Monthly Meeting…” Daily State Sentinel, October 6, 1868, 4, accessed HSC ; “Our Orphans,” Indianapolis Journal, May 24, 1869, 4-5, accessed ISL microfilm; “The Annual Election of the Officers…” Indianapolis News, May 4, 1870, 4, accessed HSC; “The Orphans’ Home,” Indianapolis News, May 27, 1872, 4, accessed HSC; “Appeal to Citizens,” Indianapolis News, July 13, 1874, 2, accessed HSC; “Charitable Waifs,” Indianapolis News, May 22, 1876, 3, accessed HSC; “Charitable Work,” Indianapolis News, May 28, 1877, 3, accessed HSC; “The Orphans,” Indianapolis News, May 16, 1881, 3, accessed HSC; “Indianapolis Orphan Asylum,” Indianapolis News, May 9, 1884, 3, accessed HSC; “Affairs of the Orphan Asylum,” Indianapolis News, May 4, 1887, accessed HSC; Board of Managers Minutes, 1885-1917, BV 3653, M 0983, 11, 20, 24, 41, 46, 49, 60, 332, 334, Indiana Historical Society; Foster, Mrs. Benjamin Harrison, 11-12.

The exact date that Harrison joined the Indianapolis Orphans Asylum is unknown. Her early biographer and friend, Harriet McIntire Foster, wrote that Harrison was a member for thirty-two years, from 1860 until her death in 1892. A newspaper article dated June 29, 1889, titled “Caring for the Orphans,” found in the Board of Managers Minutes for the Indianapolis Orphans Asylum noted that “Mrs. Benjamin Harrison was elected a manager in 1862.” No other documentation could be found by IHB staff that possibly aligns Harrison with the Orphans Asylum, which was founded in 1851, except for one newspaper article from 1856. The article announced that a “Mrs. Harrison” adopted a resolution for the Widow’s and Orphan’s Asylum. A State Sentinel article lists Mrs. Benjamin Harrison as a manager of the asylum in 1862. Other newspaper articles note her presence on the board of managers throughout the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s. She was elected one of three Vice Presidents in 1869, and elected Secretary in 1870, a position she served until approximately 1874, in which newspaper articles note that she was again a manager. The Board of Mangers Minutes make it clear that Harrison continued to participate as much as she could while she lived in Washington, DC in the 1880s and early 1890s. In December 1890, Harrison visited the Board of Managers and the managers adjourned the meeting to show Harrison the asylum and improvements the board had made since Mrs. Harrison had left for Washington, D.C. as First Lady. When Harrison died in 1892, the board adopted a resolution, noting the organization had lost “an efficient co-laborer and wise counselor and the orphans a loving, sympathetic friend.”

[7] The Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin vol. 1 (Baltimore: 1890), 103, accessed HathiTrust; “Woman’s Medical Fund,” The Baltimore Sun, November 1, 1890, 6, accessed ProQuest; “Mrs. Harrison at the Head,” Topeka State Journal, November 3, 1890, 8, accessed Newspapers.com; Mary E. Garrett to Mrs. Benjamin Harrison, November 5, 1890, Benjamin Harrison Presidential Papers, Library of Congress, #25578, Series 1, Reel 29, submitted by applicant; “For A Woman’s Medical School,” New York Tribune, November 15, 1890, 5, accessed ProQuest; “Women Medicos: Their Advanced Education to be Provided,” Oakland Daily Tribune, January 8, 1891, 8, accessed Newspapers.com; “Miss Garrett’s Gift: She Presents $306,977 to Johns Hopkins Medical School,” Baltimore Sun, December 30, 1892, 8, accessed Newspapers.com ; Kathleen Waters Sander, Mary Elizabeth Garrett (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007), 150-175, 190; “A Timeline of Women at Hopkins,” accessed Johns Hopkins Magazine.

Upon his death in 1873, Baltimore merchant Johns Hopkins left $7 million to found Johns Hopkins University and Johns Hopkins Hospital. The university opened in 1876 and hospital in 1889. An accompanying medical school was supposed adjoin the hospital, however the trustees ran out of money for the school in 1889. The trustees struggled to find a single, wealthy male donor to contribute $100,000 to finance the school. Five Baltimore women, Martha Carey Thomas, Mary Elizabeth Garrett, Mary Gwinn, Elizabeth King, and Julia Rogers, four of whom were daughters of Johns Hopkins trustees, offered to raise $100,000 to establish the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, on the condition that the school accept women on the same terms as male applicants. They immediately reached out to prominent women in cities across the United States and urged them to form local fundraising committees. They asked Caroline Harrison to lead the Washington, D.C. fundraising committee, which Harrison accepted in late October or early November 1890. According to Kathleen Waters Sanders, a biographer of Mary Elizabeth Garrett, Harrison’s endorsement “was important, lending the campaign credibility and national visibility.” Women across the country collectively raised $100,000 and submitted it to the trustees of the university on October 29, 1890. Harrison attended the presentation of the $100,000 to the trustees with other committee members. The Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin from November 1890 noted that the $100,000 would be received as long as the:

medical school is opened to women, whose previous training has been equivalent to the preliminary medical course prescribed for men, shall be admitted to such school upon the same terms as may be prescribed for men.

According to an editorial by Mary Elizabeth Garrett to the Evening Star, the medical school decided that an additional $400,000 was needed to open the school, which “women of the various committees, those already organized and others springing up all over the United States, intend to devote their energies.” Women continued to raise money for the cause. Harrison hosted a major event on November 14, 1890 in Baltimore that garnered enormous press coverage and attracted 1500 prominent local women. Eventually Garrett gave $306,077, bringing the total to $500,000 in December 1892, shortly after Harrison’s death. The medical school opened in 1893, the first coeducational, graduate-level medical school in the nation. Three of the eighteen students in the first class were women.

[8] “White House Extension,” Evening Star [Washington, D.C.], February 2, 1890, 11, accessed Newspapers.com; “New White House Plans: Mrs. Harrison’s Ideas for Extension of the Mansion,” Chicago Tribune, August 24, 1890, 26, accessed Newspapers.com; US Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds, Extension to the Executive Mansion, 51st Cong., 2nd Session., 1891, 1-4, accessed GoogleBooks; “In Memoriam,” American Monthly Magazine, 511-512; Frank G. Carpenter, Carp’s Washington, (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1960), 302, accessed HathiTrust; Foster, Mrs. Benjamin Harrison, 18.

After the Harrisons moved into the White House, Caroline Harrison became “concerned over the condition of the house provided for the Chief Executive and his family.” According to Representative Seth Milliken’s report to the House of Representatives on the extension to the Executive Mansion, Harrison invited past First Lady Harriet Lane Johnston (niece of bachelor President James Buchanan) to visit and the two began to discuss “the absolute inadequacy of the accommodations” and noted there often was not enough space to entertain and host important foreign leaders and dignitaries. Milliken acknowledged that since the Buchanan administration, the problem had “been growing worse ever since on account of the immense increase of public business, and the consequent encroachment upon the private portions of the mansion.” Mrs. Harrison began to lobby for an expansion and renovation of the White House by adding wings to either side of it. Her plan featured maintaining and preserving the current mansion instead of drastically altering the original structure or constructing an entirely new building. At the time, other senators and representatives had expressed interest in a variety of plans, including constructing a replica of the White House on the grounds and adding an additional story to the current White House. Milliken noted that Harrison’s ideas centered on the “preservation of the present mansion in all its stately simplicity and historic interest untouched, and the addition of wings (art) on the east and (official) west attached to the present building.” Her obituary in the American Monthly Magazine noted that Harrison “knew that the old mansion must be preserved, not simply as a relic or a public office, but as a home,” thus she also worked to save and document the White House’s furnishings and collections (see footnote 11 on furniture and footnote 12 on the china collection).

[9] Caroline Harrison’s White House Diary, transcription, 1889-1890, accessed C-SPAN; “White House Extension,” Evening Star, February 8, 1890, 11, accessed Newspapers.com; “An Ideal Mansion: Mrs. Harrison’s Artistic Designs for a Home for the Presidents,” Evening Star [Washington, D.C.], March 8, 1890, 9, accessed Newspapers.com; US Treasury Department. Annual Report of the Register of the Treasury (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1890), 99, accessed HathiTrust; US Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds, Extension to the Executive Mansion, 51st Cong., 2nd Sess., 1891, 1-4, accessed GoogleBooks; Thomas P. Cleaves and James C. Courts, Statements Showing Appropriations, New Offices &C., 51st Congress, 2nd Sess., (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), 209-210, accessed HathiTrust; “Mrs. Harrison’s Suggestion for the Extension of the Executive Mansion,” 1891, National Archives & Records Administration, 17370308, Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital, accessed NARA; “An Addition to the White House,” Atlanta Constitution, January 15, 1891, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Mrs. Harrison Directing Repairs to the White House,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 31, 1891, 10, accessed Newspapers.com; Irwin Hood (Ike) Hoover, Forty-Two Years in the White House (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1934), 3, 6, 8-10; Carpenter, Carp’s Washington, 301-304, accessed HathiTrust; Anne Chieko Moore, Caroline Lavinia Scott Harrison (New York: Nova History Publication, 2005), 35.

Irwin Hood (Ike) Hoover, who worked forty-two years as a White House caretaker starting in 1889, noted in his autobiography that the White House “really took on its modern aspect” during the Harrison administration. He wrote “Prior to the coming of the Harrisons, it [the White House] had undergone only the routine repairs, except for the addition, about 1825, of the North Portico.” Harrison’s note about rats in her White House diary in 1889 underscored the disrepair of the building: “The rats have nearly taken the building so it has become necessary to get a man with Ferrets to drive them out. They have become so numerous and bold that they get up on the table in the Upper Hall and one got up in Mr. Halford’s bed.” Representative Milliken emphasized that it was Mrs. Harrison who spearheaded the campaign to expand and renovate the White House. She met with architect Frederick D. Owen, who drew up plans depicting Mrs. Harrison’s vision. His original plans, housed at the National Archives and Records Administration, are titled “Mrs. Harrison’s Suggestion for the Extension of the Executive Mansion.” She began taking interviews with journalists to generate public support. The Evening Star reported that Harrison had invited the committee on public buildings and grounds to visit the executive mansion to examine “its condition for the purpose of repairs incident to decay and cheap and insecure workmanship and to enable Mrs. Harrison to state her ideas in reference to all extension to the building.” Journalist Frank Carpenter also noted that Harrison was organizing and attending conferences with senators and representatives about White House improvements. Despite Harrison’s work, her bill to provide funding to expand the White House, presented by Representative Milliken, did not pass. Though it went through the Senate, it failed in the House because President Harrison had ignored the Speaker of the House’s choice for collectorship of Portland, Maine. However, she did receive approximately $60,000 in appropriations to redecorate and renovate the interior and additional funds to add electricity to the building. This was a big accomplishment in the late 1880s, as Congress had only appropriated about $717 to repair the White House.

To modernize the interior, the Harrisons added electricity, painted the walls, installed private bathrooms, completely redid the kitchen, replaced all the dirty and moldy floors, rebuilt the old conservatory, and added greenhouses. She also redecorated many parlors and private rooms. In her diary, Caroline describes the construction of new bathrooms, adding new bedrooms, and taking up the carpets, noting “I don’t suppose the floors had been scrubbed for many years.” The Atlanta Constitution noted that “it was only upon Mrs. Harrison’s personal solicitation that the house appropriation committee provided for them. Carpenter described the renovations as “so great that when the Clevelands came back a few years later, they hardly recognized the house which they had left only four years before.”

[10] “White House Furniture: An Interesting Interview with Mrs. Harrison on an Interesting Subject,” Evening Star [Washington, D.C.], January 18, 1890, 6, accessed Newspapers.com; “Mrs. Harrison: Her Ideas of How the White House Accounts Should be Kept,” Fort Worth Daily Gazette, June 1, 1890, 8, accessed Newspapers.com; Mrs. De B. Randolph Keim, “Mrs. Harrison’s Earnest Endeavor for the Additions to the Executive Mansion,” American Monthly Magazine 20, no. 2 (February 1902): 103, accessed NSDAR; Foster, Mrs. Benjamin Harrison, 18; Carpenter, Carp’s Washington, 302, accessed HathiTrust; Rae Lindsay, The Presidents’ First Ladies (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Gilmour House, 2001), 60.

Harriet McIntire Foster recalled that Harrison “had a cultured taste for and appreciation of historical relics connected with American history. . . . She desired to make not only a comfortable home for the President’s families, but a depository for furniture, silver, glass, china pictures, and rugs.” Frank G. Carpenter, a correspondent for the Cleveland Leader who covered Washington, D.C. during the Harrison administration noted that “At the request of Mrs. Harrison, the President has ordered an inventory of the furniture of the Executive Mansion. Even the old bits stored away in the attic are to be listed, for Mrs. Harrison is anxious that pieces which have historic value or connection with presidential families of the past shall be preserved.” Carpenter noted that before this action, many White House pieces were sold at auction at the end of each president’s administration. He wrote “the source of each article is now being traced so that both its intrinsic and historical value may be determined.” The Evening Star reported that Harrison had recently gone through the contents of the entire White House “to ascertain what household articles of art, historic interest and vertu [sic] have escaped the carelessness of servants or auctioneer’s hammer.”

[11] “Rookwood Pottery,” Indianapolis Journal, March 12, 1887, 8, accessed HSC; “Pottery Display,” Indianapolis News, December 14, 1887, 1, accessed HSC; Caroline Scott Harrison, Early Design Inspiration for Harrison China, 1891, accessed White House Historical Association; “Mrs. Harrison Dead: The President’s Wife Expires this Morning,” The Baltimore Sun, October 25, 1892, 1, accessed ProQuest; Brooks, “Memories of Our First President General;” Foster, Mrs. Benjamin Harrison, 18; Carpenter, Carp’s Washington, 300; Ellen Paul Denker, “Liberating the Creative Spirit: China Painters of Indiana,” Traces, 6, no. 1 (1994): 33-34, accessed Indiana Historical Society; “Official White House China: China Room-1918,” White House Collection, accessed White House Historical Association.

Harrison first became interested in china painting in Indiana, after taking a class in Richmond, Indiana from Paul Putzki. In the 1880s, she exhibited some of her work alongside Putzki’s at exhibitions for the Art Association of Indianapolis. She brought her passion to Washington, D.C. and started china painting classes in the White House for Washington, D.C. society women. Harrison is also credited with laying the groundwork for the celebrated White House China Collection. Her acquaintance, Harriet Foster, noted that Harrison began to collect and document china from past administrations while she began renovations of the White House (see footnote 10). Foster wrote “she immediately began a valuable collection to be preserved, in cabinets, of the scattered remnants of the china of former Presidents.” Her niece, Kate Scott Brooks, recalled that before Harrison, “the custom had always been for an incoming Presidential family to select their own china that used by the predecessors being sold or given away.” Harrison initiated a new practice in which all china was to be kept at the White House and reused by incoming administrations. She also inventoried all remaining china and identified which administration it belonged to. Lastly, she designed the Harrison china set, which featured corn ears, stocks and tassels. First Lady Edith Wilson later established the current White House China Collection room to store and display the china on the Ground Floor of the White House in 1917.

[12] “Women and the Revolution,” Evening Star [Washington, D.C.], October 13, 1890, 7 accessed Newspapers.com; Caroline Scott Harrison, “Address to the First Continental Congress,” February 22, 1892, accessed Daughters of the American Revolution; “Opened by Mrs. Harrison: First Continental Congress of Daughters of the American Revolution,” New York Tribune, February 23, 1892, 5, accessed ProQuest; “The Proposed Building For the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution,” American Monthly Magazine 1, no. 1 (July 1892): 14-15, accessed NSDAR; “In Memoriam,” American Monthly Magazine, 513-514, accessed NSDAR; Flora Adams Darling, Founding and Organization of the Daughters of the American Revolution (Philadelphia: Independence Publishing Company, 1901), 30, 39, 59-61, 131-132, 141, accessed HathiTrust ; Foster, Mrs. Benjamin Harrison, 22-23; Teachout, “Forging Memory,” 11, 20-21, 30, 45, 95-96; National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, “What We Do,” accessed NSDAR.

The Daughters of the American Revolution was organized in 1890, after the Sons of the American Revolution refused to accept female applicants. The founders, Mary Desha, Flora Adams Darling, Ellen Hardin Walworth, Eugenia Washington, and Mary S. Lockwood decided to ask Caroline Harrison to serve as President General of the Daughters of the American Revolution. They hoped her status as First Lady would elevate their organization, give it credibility, and attract more members. According to Darling, she and Lockwood went “to see Mrs. President Harrison, who said she would accept if her papers of admission could be secured.” On October 13th, 1890, the Evening Star of Washington, D.C. announced that the DAR had formed and that Caroline Harrison would serve as the first President General. The organization’s goals were “the securing and preserving of the historical spots of America and the erection thereon of suitable monuments to perpetuate the memories of the heroic deeds of the men and women who aided the revolution and created constitutional government in America.”

Harrison delegated many of the day-to-day logistics of the organization to other DAR officials, but was one of the first to understand the political influence the DAR could have and helped advise the board on how to promote the DAR. Her obituary in the DAR’s magazine American Monthly noted that “the broad mind and strong patriotic instincts of Mrs. Harrison grasped at once the meaning and the possibilities which lay in the germ of this great organization when fluttering in the first throes of its existence.” Her acquaintance and early biographer, Harriet McIntire Foster agreed and described “her instant recognition of the patriotic greatness of the organization of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution.” She advised on such matters as making sure the chairman of the executive committee of the organization was “a married lady with a home and permanent address, one of social distinction,” instead of one of the single or widowed co-founders to legitimatize the organization. She also helped quell internal disagreements within the organization in its early years. For example, she called a meeting on October 5, 1891 of every officer to establish “complete unity of action and perfect harmony of feeling throughout the National Society.” At the time, just two years after it was formed, the organization had 1,307 members. Before she died, Harrison took an interest in the construction of a headquarters for the National Society, proposing in a meeting March 19, 1891, “that the Board of Management should proceed at once to formulate a plan for providing the Society with the necessary building” and:

advised that the enterprise take the form of a joint-stock company, to be managed upon sound business principles, and upon such a plan as should ensure to the stockholders a reasonable interest upon their investment . . . she called attention to the success of the Indianapolis Propylaeum, built and managed by women, and which had declared a dividend in the first year.

Memorial Continental Hall, the first national headquarters for the society, was commissioned in 1902 and completed in 1910, located on 1776 D Street NW in Washington, DC.

According to the DAR website, the organization has accepted over 950,000 members since its founding and has helped finance or construct numerous monuments commemorating important events in American history, restored historic properties, and maintained historic sites, including homes, cemeteries, forests, buildings, and landmarks. It also preserves and provides access to genealogical records, historical documents and artifacts, providing scholarships and running educational programs, and supporting veterans.

[13] E.S. Wells, “Mrs. Harrison Very Low: Great Alarm Felt Over Her Condition,” Detroit Free Press, September 15, 1892, 9, accessed ProQuest; “The End of a Lovely Life,” Detroit Free Press, October 25, 1892, 1, accessed ProQuest; “Caroline Scott Harrison,” Woman’s Tribune, October 29, 1892, 1, accessed Nineteenth Century Collections Online.

Obituaries for Caroline Scott Harrison noted that Harrison died October 25, 1892 in the White House. Though Harrison had battled respiratory illnesses for much of her life, in mid-September 1892, her physicians told the press that Mrs. Harrison’s primary disease was “pulmonary tuberculosis of right side,” with a “recent complication, subacute pleurisy, with rapid effusion of water in the right chest.” Mrs. Harrison never recovered and died about five weeks later from the disease.

Keywords

Women, Politics, Arts and Culture