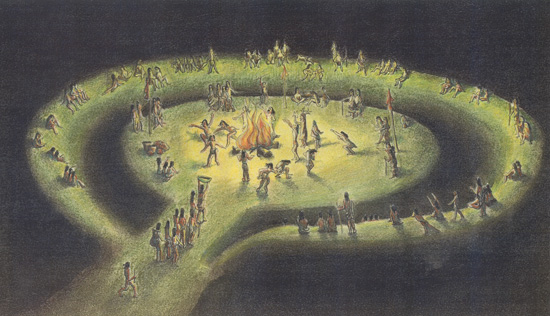

Artist's rendering of a ceremony on the Great Mound at Mounds State Park.

Adena Culture

In the Early Woodland Period, from 1,000 to 200 B.C., there was a people group in Indiana we now call the Adena culture. The term is taken from the name of the farm of Thomas Worthington, who lived in Chillicothe, Ohio in the 19th century. Archaeologists named this civilization because they did not know what members of this group called themselves.

The Adena were not one large tribe, but likely a group of interconnected communities living mostly in Ohio and Indiana. The Adena culture is known for food cultivation, pottery, and commercial networks that covered a vast area from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico.

Over a period of 500 years, the Adena culture transformed into what we call the Hopewell tradition. Much like the Adena, the Hopewell were not one large group, but were a group of interrelated societies. Just like with the Adena, archaeologists also coined the name Hopewell.

Hopewell Tradition

The Hopewell’s large trade networks connected them with other cultures. Some archaeologists see the Hopewell as the pinnacle of the Adena. The Adena-Hopewell had a social hierarchy. The cultural evolution from hunter-gatherers to agriculture meant stability for the people as well as economic expansion and population growth.

Out of these cultural changes, tribes and chiefdoms emerged. No evidence exists of the Hopewell in Indiana after A.D. 500, but some scholars think that some time before European contact, the Hopewell could have become what we know now as the Miami or Shawnee.

The Woodland Period is often associated with the building of mounds, also called earthworks. Many of these mounds were built by the Adena. The mounds were used by Woodland peoples for various religious and ceremonial purposes. More than 300 of these mounds have been identified in central Indiana. All of them are on the eastern side of a river, leading scholars to think the location of a mound was deliberate.

The Mississippian Culture

The Mississippian Culture was another mound-building civilization. This group lived in the Midwest from 800 to 1600. The Mississippians built large mounds with platforms on top. On these platforms they built houses and public buildings. The staple food for this culture was maize, also known as corn. Like the Adena-Hopewell, Mississippians had a large trade network.

Evidence suggests that the Mississippians had a more fully evolved social hierarchy than the Adena-Hopewell. The hierarchy used the chiefdom as its political structure. The Mississippians left behind physical evidence of their daily life in the form of artifacts, giving us clues about their daily life. “Mississippian” is a name given to this group by modern archaeologists. There are no records of their original name.

The Mississippian people were agricultural, meaning they grew crops on a large scale to feed members of their society. Agriculture was the primary source of food production for Mississippian settlements. As food storage improved, these populations were able to store food year-round and save seeds for planting the next year. And, living on a river, they supplemented their diet with fish and mussels.

The largest Mississippian site in Indiana is Angel Mounds State Historic Site near Evansville. Falls of the Ohio State Park, located along the Ohio River like Angel Mounds, is known to have had Mississippian settlements. Other parks along the Ohio River could well have been home to Mississippian settlements as well (Clifty Falls, O’Bannon Woods, Charlestown, Harmonie).

At some point, about 700 years ago, the Mississippians suffered a terrible drought that led to widespread loss of crops. This looming starvation drastically changed the daily life of this culture. People left their towns, farms, villages, and hamlets to form nomadic hunting and gathering bands.

Artifacts housed at Falls of the Ohio State Park

These prehistoric artifacts were used by Native Americans between 500 and 3,000 years ago.