Daily Life for Native American Groups in the Lands that Became Indiana

Several prominent Native American nations lived in the Indiana region around the 19th century. The largest were the Miami, Shawnee, and Illinois. Refugees from other nations also resided in the area, including the Lenape (Delaware). Indiana was home to several bands of Miami, including Wea and Piankashaw. All of Indiana was within Miami territory, with most of its towns in the northern portion of what became the state’s boundaries.

At the time of European encroachment, indigenous groups primarily spoke Algonquian languages. These groups lived in villages composed of round, dome-shaped dwellings called wiikiaami made with woven reeds. Many of the men were hunters, trappers, and traders who sold goods like furs and meat to the Europeans in exchange for desirable items like metal cooking pots. Many of the women worked in agriculture and took care of the home, preparing food, making clothing, caring for children, and determining what was needed for daily life.

On a broader level, the Miami villages contained multiple large extended family groups called clans. Each village was governed by separate men’s and women’s councils, each of which was represented by a civil chief. Each village also had multiple war leaders who would lead groups of men during times of armed conflict.

Each Native American nation had its own distinct culture and language, but there were some practices that most shared. Men and women interacted freely within these communities and women held a lot of power over home and village life. Women were responsible for agriculture and knew how to grow crops together to avoid soil erosion. Villages shifted their locations in order to allow the environment to replenish. The many diverse European cultures who colonized North America found these practices strange and were often confused by the structure of Native American society. They often expected Native Americans to have one authoritarian male leader, and they often did not understand the intricate social ties that unified the Miami, Shawnee, Illinois, and others.

Beaver Wars

During a conflict known as the Beaver Wars, most Native American inhabitants fled the territory that became Indiana. The conflict was produced by decades of population decline, disruptions due to trade with Europeans, and conflicts over hunting grounds. The Haudenosaunee, often called the Iroquois, received support from the Dutch and English colonizers as they invaded the homelands of peoples living in what is today Ohio and Indiana. In their struggle to maintain communities and eventually return to their homelands, tribes like the Miami, Potawatomi, and Illinois were aided by the French. These groups only returned after the conclusion of the conflict in the late 1690s and early 1700s. Pay a visit to Potato Creek State Park and Indiana Dunes State Park to see where some of these conflicts took place and where Native peoples were living.

The Miami and Potawatomi were the most prominent tribal nations in this area during the Beaver Wars, but by the 1780s, the Lenape (Delaware) and Shawnee both built prominent villages in what later became Indiana. The original homelands of the Lenape were in eastern North America and they were forced westward by successive European invasions. The Shawnee homelands were in the Ohio River Valley, which they were forced to abandon after the end of the American Revolution. The Lenape settled villages in the White River Valley in what became central Indiana and both the Lenape and the Shawnee settled in the Maumee River Valley in the northeast of the state.

Indian Removal Acts

A group of Potawatomi came to Indiana by way of the Michigan territory and migrated to Indiana at some point following the Beaver Wars. Pokagon State Park is named after Leopold and Simon Pokagon, two leaders of this band of Potawatomi. Some Potawatomi also lived farther to the west along the St. Joseph and Kalamazoo rivers.

During the 19th century, conflicts with Europeans eventually came to a head, resulting in the dispossession and forced removal of the indigenous peoples. Over a period of about fifteen years beginning in 1830, indigenous nations were forcibly removed from Indiana to territories farther west when the United States Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830.

As a result of the poverty and oppression of the early 1800s, the Wea and Shawnee made the difficult decision to move west of Indiana. This left the Miami and Potawatomi as the two remaining tribal nations in the state in the 1830s.

The Potawatomi village, led by Chief Menominee, resisted as long as possible. He and his village were removed along what is called the Potawatomi Trail of Death in 1838. Of the nearly 900 people removed in 1838 around forty of them died along the journey. The devastation did not end there. Forcing a group to leave their ancestral homelands and all that they know to go to a place that is unfamiliar is potentially catastrophic for the culture because of the shared set of values, ideas, concepts, and behaviors that defines a group.

In 1846, the Pokagon Band had moved north into Michigan and the Miami Nation along with over 320 of its citizens were forcibly removed from the state. However, around 150 Miami were allowed to remain living on land that they owned as individuals or families.

The Miami, Potawatomi, and many other Native American nations have survived the years of loss that followed forced removal. Today, many tribal nations are thriving again despite the challenges presented by their past treatment.

More information

Prophetstown and Tecumseh’s Confederation

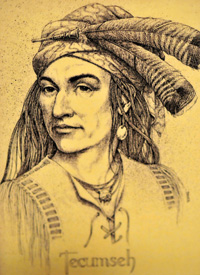

The Shawnee migrated to northeast Indiana after Americans burned their towns in the central Ohio Valley in the late 18th century. From there, they found their way to the Vincennes area in search of better hunting opportunities. The Shawnee brothers Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa led a confederation of Native American groups to try to win back their land and existence from the encroachment of European-Americans. Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa believed that uniting with other nations was essential to victory, and is reported to have said “a single twig breaks, but a bundle of twigs is strong.” The brothers established a town called Prophetstown, because Tenskwatawa was also known as The Prophet, near present day Lafayette, Indiana which is now Prophetstown State Park, Indiana’s most recent state park.

The Shawnee migrated to northeast Indiana after Americans burned their towns in the central Ohio Valley in the late 18th century. From there, they found their way to the Vincennes area in search of better hunting opportunities. The Shawnee brothers Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa led a confederation of Native American groups to try to win back their land and existence from the encroachment of European-Americans. Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa believed that uniting with other nations was essential to victory, and is reported to have said “a single twig breaks, but a bundle of twigs is strong.” The brothers established a town called Prophetstown, because Tenskwatawa was also known as The Prophet, near present day Lafayette, Indiana which is now Prophetstown State Park, Indiana’s most recent state park.

As European-American settlers moved westward, the Shawnee leader Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa (also known as the Prophet) moved their followers from Ohio to the junction of the Wabash and Tippecanoe rivers. It was at this location in 1808 that the brothers founded Prophetstown.

Tecumseh believed that creating a confederacy of several tribes would halt the advance of the settlers. He also hoped to build on memories of the confederacy that resisted the Americans in the late 18th century. Tenskwatawa preached Indian renewal and cultural purity. He discouraged the use of alcohol and disdained the adoption of the settlers’ ways. Often, people view Tecumseh as the primary leader, but in fact Tecumseh rose to prominence only after Tenskwatawa had been rallying support for some time.

Tecumseh Searches for Support

Tecumseh’s recruiting efforts led him to New York, Canada, Arkansas, Minnesota, and perhaps as far south as Florida. He visited other Native American nations and persuaded them to abandon their tribal animosities to fight the larger enemy: the United States, but some other native leaders, such as the Miami’s Little Turtle and Shawnee chief Black Hoof, argued for peaceful adaptive resistance to U.S. efforts to take their land.

Tecumseh hoped his confederation’s large numbers would dissuade European-American settlement. By 1808, warriors from other nations were congregating at Prophetstown. William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory, knew of this increased Native American presence. Groups represented there were the Potawatomi, Shawnee, Kickapoo, Delaware, Winnebago, Wea, Wyandotte, Ottawa, Chippewa, Menominee, Fox, Sauk, and Creek. Despite this land being within Miami territory, there is not evidence to suggest that they had a presence at Prophetstown beyond a couple of individuals.

The Battle of Tippecanoe

Harrison respected and feared Tecumseh as a statesman. Concerned by the strengthening Confederation, Harrison, in November 1811 (while Tecumseh was away), moved troops to within a half-mile of Prophetstown. The Prophet feared an attack, so in an effort to defend Prophetstown against Harrison’s offensive, he initiated a surprise strike on Harrison’s encampment. In the early morning of November 11, Tenskwatawa’s warriors surrounded Harrison’s men. Harrison’s sentry sounded the alarm and the battle began. Both sides suffered heavy losses. It is likely that Tenskwatawa’s men ran out of ammunition, pulled back, and escaped to Prophetstown. The residents of Prophetstown fled and Harrison’s troops burned to the ground.

Harrison respected and feared Tecumseh as a statesman. Concerned by the strengthening Confederation, Harrison, in November 1811 (while Tecumseh was away), moved troops to within a half-mile of Prophetstown. The Prophet feared an attack, so in an effort to defend Prophetstown against Harrison’s offensive, he initiated a surprise strike on Harrison’s encampment. In the early morning of November 11, Tenskwatawa’s warriors surrounded Harrison’s men. Harrison’s sentry sounded the alarm and the battle began. Both sides suffered heavy losses. It is likely that Tenskwatawa’s men ran out of ammunition, pulled back, and escaped to Prophetstown. The residents of Prophetstown fled and Harrison’s troops burned to the ground.

One of the largest Native American confederations ever in North America was wounded, but Tecumseh continued rallying support for his cause until his death at the Battle of the Thames in 1813.

Today, the historic location of Prophetstown falls within the boundaries of Prophetstown State Park. More than two hundred years after Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa sought to form their confederation, Native American tribal nations still gather to honor and celebrate the site’s history and importance.